Brilliant Examples of Minimal Art

May 23, 2016

Minimal art is easy to misunderstand. Partly that’s because artists, critics, art historians and art theorists often disagree about Minimalism’s objectives and defining characteristics. Some of Minimalism’s biggest names refuse even to associate with the label. Still others claim to make minimal art, though their work seems to defy Minimalism’s ethos. Rather than wasting time in a battle of semantics, we keep an open mind. We’ve previously described Minimalism as a perspective that “less is more.” We don’t mean that there’s less going on in minimal art, or that there’s less to enjoy, but that minimal art does more with less. A great work of minimal art stands apart as something specific that can be appreciated by anyone at any time in any context simply for what it is.

Form and Color

When Ellsworth Kelly died in December 2015 at age 92, he was one of Minimalism’s most influential painters. It may not seem so by looking at his paintings, but Kelly was controversial even among other artists. Kelly’s paintings contained no sense of composition, no theme, and no identifiable meaning (symbolic or otherwise). Perhaps the controversy rose from their simplicity. Or perhaps it came about because viewers had a hard time understanding works that only referenced themselves.

Ellsworth Kelly - Yellow Piece, 1966, Synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 75 x 75in, © 2020 Ellsworth Kelly

From early on in his career, Kelly’s focus was on geometric shapes and patterns and a monochromatic color palette. In order to avoid content and themes, he sometimes experimented with chance, using random color choices to dictate the direction of his paintings. Then in 1966 he had a breakthrough. He started shaping his canvases, beginning with a painting called Yellow Piece. Rather than painting, for example, a geometric shape onto a rectangular canvas, he created a canvas that was already in the shape of the form he wanted to paint and then painted the whole canvas monochromatically. This was a defining theoretical leap. Rather than a form being contextualized and contained by a shape (a rectangle), the form itself became the object.

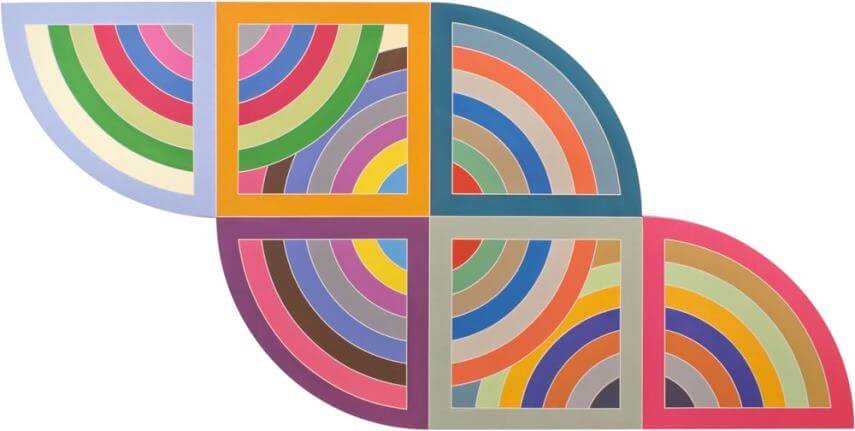

Frank Stella - Harran II, 1967, Polymer and fluorescent polymer paint on canvas, 120 × 240 in, de Young Museum, San Francisco, © 2020 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

New Beginnings

The painter Frank Stella is another minimal artist who explored the practice of shaped canvases. Stella’s Harran II is a shaped work that depicts a series of brightly colored arcs contained within a series of squares and arched triangles. Today this work is iconic among Stella’s oeuvre. It perfectly depicts what has come to be considered his signature visual language: cut out, brightly colored shapes joined with other shapes.

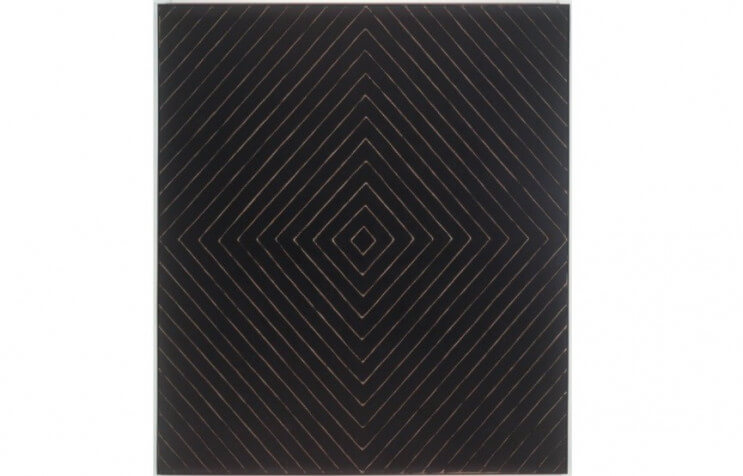

But prior to working with shaped canvases, Stella made an even more profound contribution to Minimalism with his so-called black paintings, which depicted black lines in a geometric pattern. Essentially, these paintings contain nothing more than paint on a flat surface. That may sound obvious, but what they represented theoretically is the birth of Minimalism: the idea of paintings as objects rather than depictions of something else.

Prior to the revelation that a painting didn’t have to be a painting but could be a self-associating independent object, three-dimensional art referred to paintings, sculptures, assemblages, and possibly installations. This new category, the “object,” was none of those things. It was a new theoretical category of aesthetic phenomena.

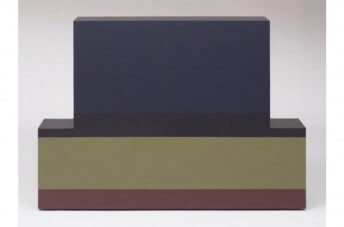

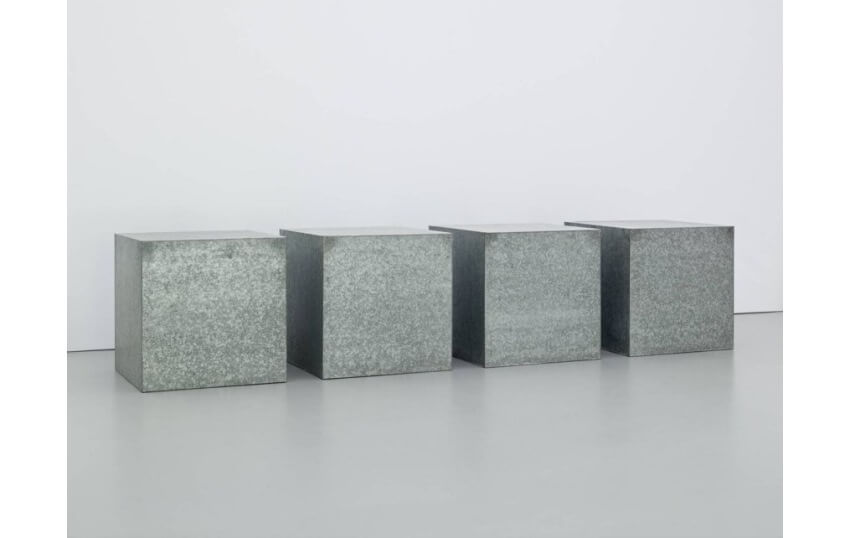

Donald Judd - Galvanized Iron 17, 1973, © Donald Judd

Specific Objects

An essay by the artist Donald Judd, called Specific Objects, best expressed this new category of aesthetic phenomena. In it, Judd explained that these new art objects in no way referenced time or society or spirituality or anything else. They were aesthetic objects without a utilitarian purpose. We’ve written before about this moment in art history, as it marked the end of the beginning of abstraction. Judd’s specific objects utilize an abstract aesthetic language, but since they’re purely objective they’re in fact literal. When Kazimir Malevich painted a black square it was considered an abstraction because it referenced ideas. It had meaning beyond being a square. Judd’s square objects reference only what they are. They have no meaning other than their own existence. They’re considered according to their own properties. They’re worthy of their own importance same as any other object in existence.

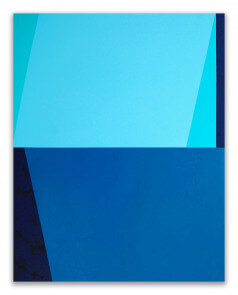

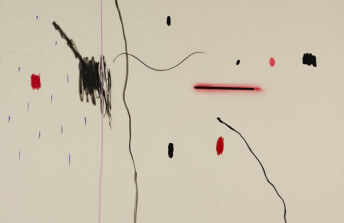

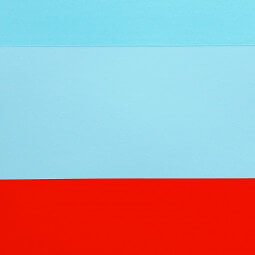

Richard Caldicott - Untitled (14), 2013, Chromogenic print (C Print), 20 x 24 in

Hard Edges

Aside from what the art references, an important aesthetic element that has come to be assigned to minimal art is what’s called the “hard edge.” This is the idea that colors on a surface occupy space next to each other in a seamless way. The perfect hard edge gives a minimal artwork the sense that it has been manufactured rather than hand-made, which takes references to the personality of the artist out of the equation.

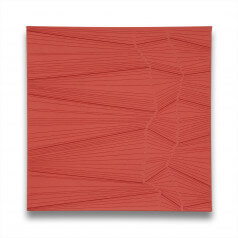

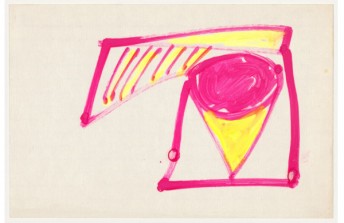

Brent Hallard - Knot (Pink), 2015, Acrylic on anodized aluminum, 13.8 x 13.8 in

An excellent example of the hard edge can be found in the work of the contemporary American artist Brent Hallard. Hallard’s work continues the Minimalist conversation by exploring geometry through monochromatic colors, exactitude and precision. But Hallard’s technique is not industrial. He uses traditional art mediums such as markers and watercolors to create his works on paper and aluminum. And there is a personal language in his oeuvre that relates not only to the work but also to the artist, reintroducing a sense of the artist’s presence.

Another contemporary hard edge artist is the British artist Richard Caldicott. Like Hallard, Caldicott updates the traditions of artists like Frank Stella and Donald Judd. A multi-disciplinary artist, Caldicott incorporates elements of drawing, photography and sculpture into his work. He mixes handmade techniques with mechanical/industrial processes such as ink-jet printing. The objects Caldicott creates exist apart from any outside reference. They’re products of processes. They’re neither object nor painting, and yet possess the ability to interact with space like a painting would.

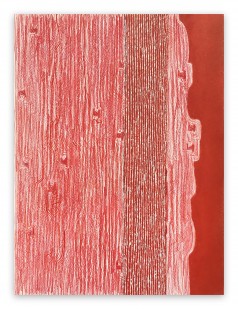

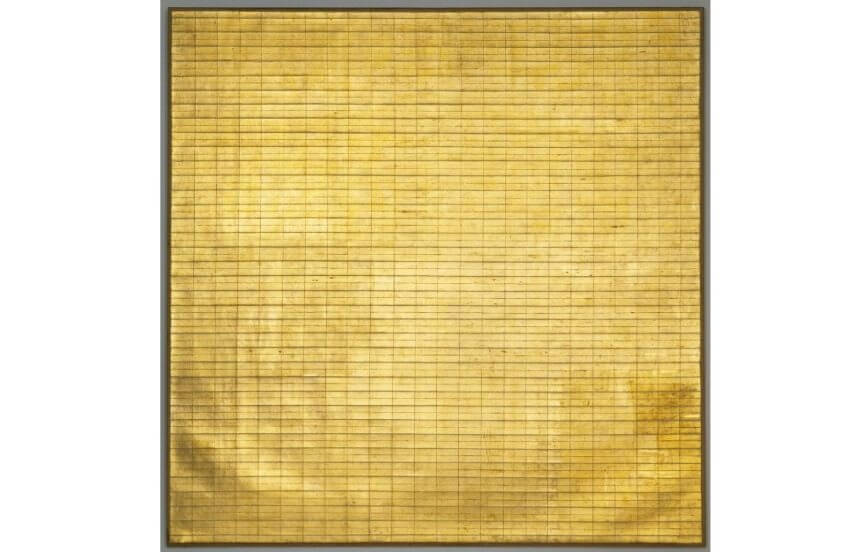

Agnes Martin - Friendship, 1963, Gold leaf and oil on canvas, 6' 3" x 6' 3", © 2020 Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lines Are Made to Be Crossed

What these contemporary Minimalists are elaborating upon is the notion that Minimalism is not some rigid set of laws. A painting can be considered minimal even if it is also emotional, or allegorical, or is handmade, or is not by definition a “specific object.” Although Stella and Judd went to great lengths to separate their work from any sense of symbolism, emotion or personality, not all artists associated with classic Minimalism took the same approach.

Agnes Martin embraced symbolism in her work. Personal expression was a vital part of her practice, and the sense of transcendence she felt while working was something she openly hoped viewers would sense. A seminal moment in Martin’s oeuvre is captured in her painting Friendship. Its strong emotional element associates it with Abstract Expressionism. But its aesthetic establishes it as a work of minimal art. We’ve written before about how Martin considered the line to represent innocence, and about how she hoped her feelings would transfer to viewers of her work. While Friendship has a sense of object-hood, it also plainly references something allegorical. Like Martin herself, it acts as a sort of bridge between Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism.

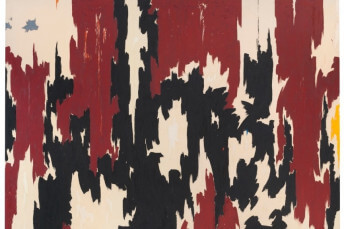

Featured Image: Frank Stella - Jill, 1959, Enamel on canvas, 90 3/8 x 78 3/4 in, © 2020 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio

Featured Artists

Richard Caldicott

1962

(UK)British

Brent Hallard

1957

(Australia)American

Macyn Bolt

1954

(USA)American

Fieroza Doorsen

1960

(UK)British