What Have We Learned from Color Field Pioneers?

Jun 7, 2016

When you think of Abstract Expressionism, what comes to mind? Do you imagine painters flinging, dripping, splattering and smearing paint across canvases in emotionally charged gestures? While Action Painting was a huge part of Ab-Ex, there was a more subdued side to the movement as well. Color Field painting as it was called, involved flat, non-painterly surfaces composed of colored space. In Color Field paintings, the artist’s personality is less visible than in Action Paintings. Whereas Action Painters conveyed their own subconscious machinations through their work, Color Field painters created works that gave viewers an arena in which to experience their own revelations.

Post-Painterly Abstraction

The term “painterly” refers to qualities that the surface of a painting can have such as stroke and texture, qualities that make the artist’s hand obvious in the work. For example a painting that features thickly applied layers of paint in which the brushstrokes are plainly visible and the painter’s individual technique is obvious could be said to be painterly. Post-Painterly Abstraction was a movement that emerged in the 1960s featuring painters who avoided making painterly works.

The phrase Post-Painterly Abstraction was coined by the art critic Clement Greenberg, who used it as the title of an exhibition that debuted in 1964 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. That exhibition featured 31 artists, many of whom were associated with Abstract Expressionism. Whereas earlier Abstract Expressionist painters such as Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning made painterly pictures in which their individual techniques were plainly obvious in the surface qualities of the works, the Post-Painterly Abstractionists made abstract works with flat surfaces where the artist’s hand was not obvious.

Robert Motherwell - Elegy to the Spanish Republic No. 110, 1971, Acrylic with graphite and charcoal on canvas, Robert Motherwell © Dedalus Foundation, Inc./Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Color Field Artists

Among the Post-Painterly Abstractionists was a group of painters that came to be known as the Color Field painters. Their name referred to the tendency these artists had to incorporate large areas of color into their works. Their color fields could entirely envelop a viewer upon close inspection of an artwork. They weren’t just painted surfaces; they were also areas in which introspection could occur.

The Color Field painters were revolutionary because rather than using the surface as a background on which to paint a subject, they caused the surface itself became the subject. They avoided forms in their paintings. There was no image of anything present. The background and foreground were one. The color fields had no context of their own but were rather a place in which the viewer could connect with something personal, perhaps something mythic, and transcend the limitations of imagery.

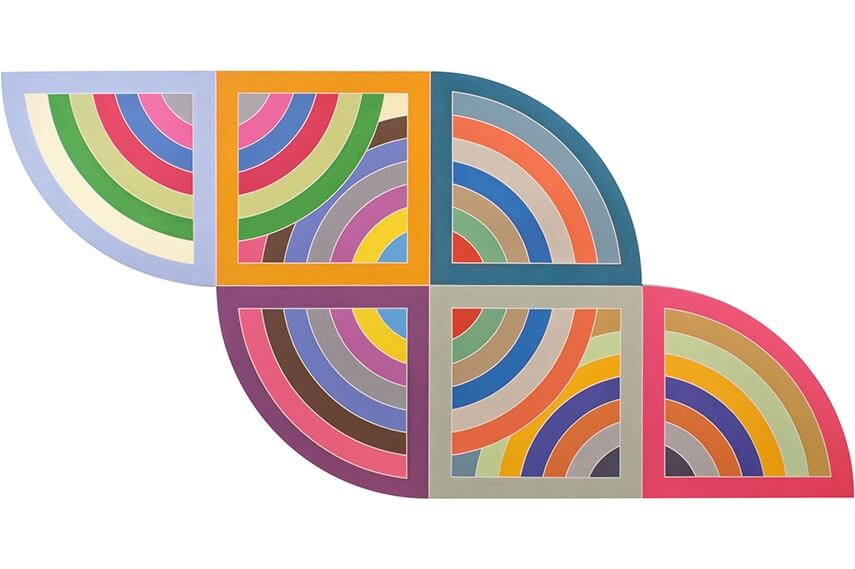

Frank Stella - Harran II, 1967, Polymer and fluorescent plymer paint on canvas, 120 × 240 in, de Young Museum, San Francisco, © 2019 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

An Arena On Canvas

Abstract Expressionism considers the canvas an arena in which something can occur. Drama and emotion occur in the Action Painters’ works. While Color Field painters also make use of the canvas as an arena, rather than their own drama playing out there it’s a place where the viewer’s own introspection could contribute to, or even entirely create the drama that emerges. Color Field paintings pull the viewer into the work, inviting them to contemplate much more than just the paint, the color, and the surface. They’re invited to contemplate themselves, using the arena of the painting as a sort of talisman on that personal journey.

Sustained reflection is required when looking at a Color Field painting. Rather than experiencing an immediate charge from an Action Painting, or feeling harmony from a geometric abstract work, or sensing nostalgia, romance or joy from a figurative work, viewers of Color Field paintings must look inward toward new revelations. But freedom can also be a burden. The Action Painters’ angst often comes from their utter freedom to express their inner selves. With Color Field paintings, that dreaded sense of freedom is passed on to the viewer.

Fields of Non-Objective Emotion

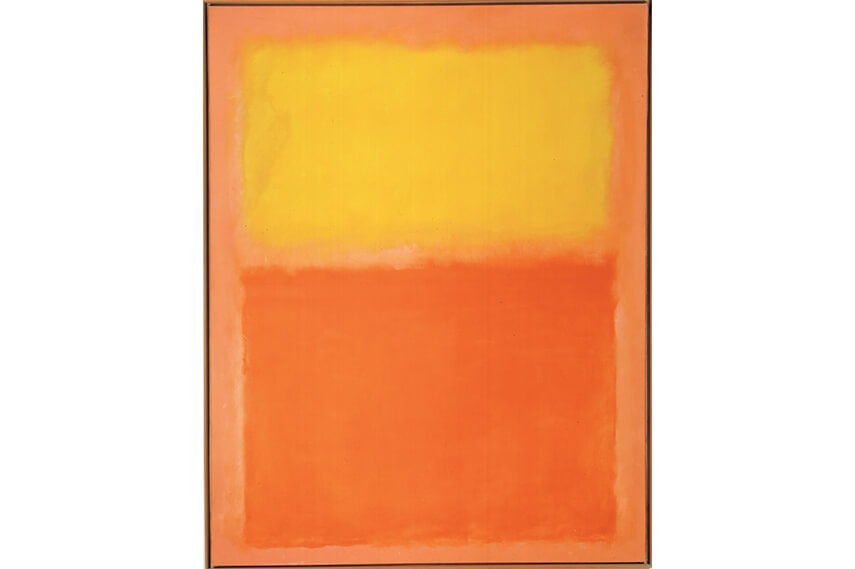

Though he rejected the label, Mark Rothko is considered by many people to be the most influential Color Field painter. Rothko’s iconic paintings consist of horizontal bands of color, which engage each other in an amorphous way, blending at their edges. His paintings sometimes consist of bright hues, such as orange, yellow or red. Other times they feature blues, browns and black. Viewers confronting these paintings are often overcome with emotion, ranging from excitement and joy to somberness and even despair. Said Rothko of his work, “The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.”

Mark Rothko - Orange and Yellow, 1956, Oil on canvas, 180.3 x 231.1 cm, Albright

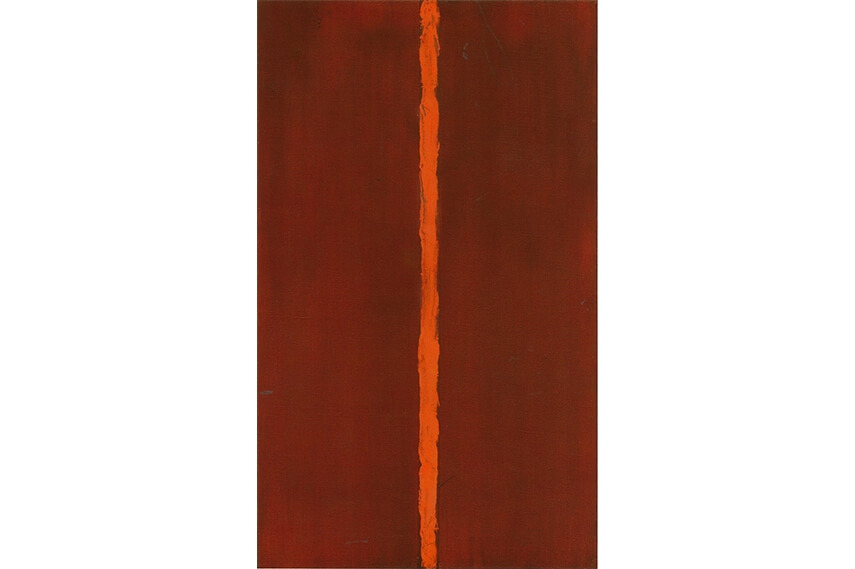

Zip Lines

Barnett Newman made works in a similar vein to Rothko’s, but they had a much different effect on viewers. Newman’s Color Field paintings feature vertical swaths of color separated by much thinner bands of color sometimes referred to as “zips.” Newman’s zip paintings sometimes feature a single zip, sometimes several. Sometimes the edges of the zips are hard, other times they blend with the surrounding color fields. The verticality of Newman’s pictures and the presence of the zips create a much different emotional response than do Rothko’s works.

Something about the zips keeps the eye from focusing too long in one spot. The vertical line can take on an anthropomorphic quality, as though it represents a figure or a lane. It draws the eye to it then shuffles the eye off again into the color fields. Newman’s works convey a sense of bravado, and seem a little more anxious than Rothko’s because of this. They invite a nervous, highly modern sort of contemplation.

Barnett Newman - Onement I, 1948, Oil on canvas and oil on masking tape on canvas, 27 1/4 x 16 1/4in (69.2 x 41.2 cm), © 2019 Barnett Newman Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Union and Revelation

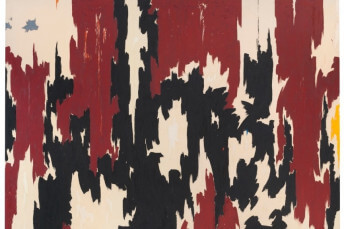

The Color Field paintings of Clyfford Still possess an entirely different presence than either Rothko’s or Newman’s. The colored spaces in them seem to be in a state of morphing or evolution. They have an organic quality. Though no specific form is present, the areas seem to shift and interact and suggest the possibility of future form. Where there is a sense of stability to the pictures Rothko and Newman made, Still’s paintings project more of a sense of change. Disparate forces come together in them, suggesting that that time for introspection is limited as everything is in flux. Said Still about his paintings, “These are not paintings in the usual sense; they are life and death merging in fearful union. As for me, they kindle a fire; through them I breathe again, hold a golden cord, find my own revelation.”

Clyfford Still - PH-971, 1957, oil on canvas, 113 1/4 in. x 148 in. x 2 1/4 in, SFMoMA Collection, © City & County of Denver, Courtesy Clyfford Still Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Outpourings of Emotion

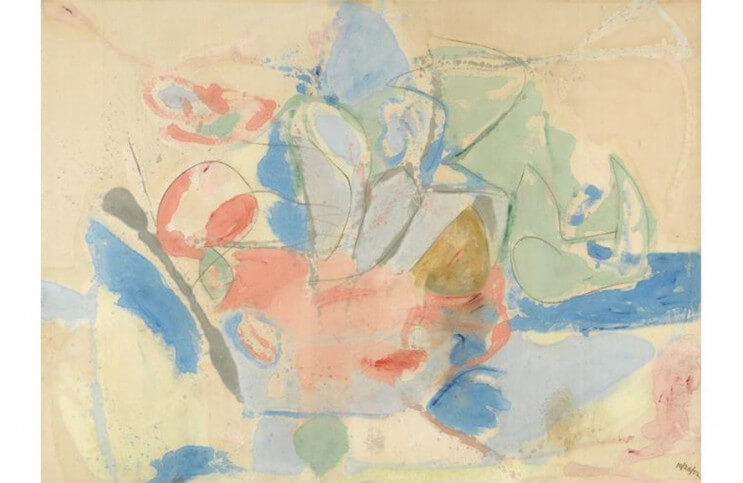

Helen Frankenthaler was one of the most innovative Color Field painters. She developed an innovative technique of staining her unprimed canvases by pouring thinned paint directly onto the surface. By pouring the paint rather than spreading it with a tool, she entirely avoided any suggestion of the artist’s hand and created an even flatter flatness. She also allowed the paint to spread and interact with the canvas in unexpected ways. The stained areas were allowed to bleed into each other, to alter one another and to combine with each other. The result of Frankenthaler’s stain technique was pictures that communicated a sense of deeply profound organic natural processes.

Helen Frankenthaler - Canyon, 1965, Acrylic on canvas, 44 x 52 in, © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Stained Look

Morris Louis was profoundly influenced by Frankenthaler’s stain technique, and he modified it in order to develop his own signature aesthetic approach. Like Frankenthaler, Louis also poured thinned paint onto his canvases in order to achieve the stained look, but he did so by utilizing a closely protected signature technique that allegedly involved something akin to folding the canvas like a funnel. The resulting color fields Louis created possess an uncanny quality that pulls the viewer in toward a mystic, introspective thought space.

Morris Louis - Salient, 1954, Acrylic resin (Magna) on canvas, 74 1/2 x 99 1/4 in. (189.2 x 252.1 cm), © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A Little More Atmosphere

Building on Frankenthaler’s and Louis’ ideas, Jules Olitski developed his own unique technique for his Color Field paintings. He applied paint to his canvases with a spray gun, lightly spraying layers of paint atop each to created luminous, atmospheric color fields that even today feel futuristic. Olitski’s signature style was also marked by hard-edged lines added near the outer edges of the canvas. That border gesture perhaps foretold the end of Color Field painting as it seems almost to reintroduce the notion of subject matter being presented within a frame.

Jules Olitski - Patutsky in Paradise, 1966, © Jules Olitski Estate/Licensed by VAGA, New York

Contemplation as the Enduring Legacy

These Color Field pioneers succeeded in creating paintings that could act not just as art objects but also as intermediaries to a viewer’s transcendental aesthetic experiences. By creating works that had no subject other than color itself, they altered the way a painting could be perceived and took painting into new mythical and spiritual realms. Contemplation is the enduring legacy of the Color Field pioneers. For many of us, their paintings are talismans, guiding us down pathways to a more introspective state of mind.

Featured image: Helen Frankenthaler - Mountains and Sea, 1952, Oil and charcoal on unsized, unprimed canvas, 86 3/8 × 117 1/4 in (219.4 × 297.8 cm), © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio