Josef Albers and The Interaction of Color

Jun 27, 2016

Throughout Modernist history an ongoing conversation between artists has endeavored to determine what is the most important element of painting. Some say form. Some say line. Some say surface. Some say subject matter. Through his art, his writing and his highly influential teaching positions, Josef Albers dedicated almost his entire career to exploring the proposition that the most important element in painting is color. His research influenced Minimalism, Color Field painters, Abstract Expressionism, Op Art, and continues to inspire a new generation of abstract artists. Though Albers passed away in 1976, his seminal book on the subject, The Interaction of Color, is still considered the most important text for young artists to read when seeking to understand the complicated ways human eyes perceive color.

Josef Albers and the Bauhaus

Albers was born in 1888, and he was an educator before he was a professional artist. He began his career teaching a general studies class to elementary students near the small German town where he grew up. In 1919, the Bauhaus opened in Weimar, Germany, offering an education unlike any that had ever been offered before. The founders of the Bauhaus intended it to be a place where artists and designers would train together in search of developing a perspective on a total art. Albers enrolled in the Bauhaus the next year, in 1920, when he was 32 years old. Five years later he became the first student to be invited to join the Bauhaus as a Master instructor.

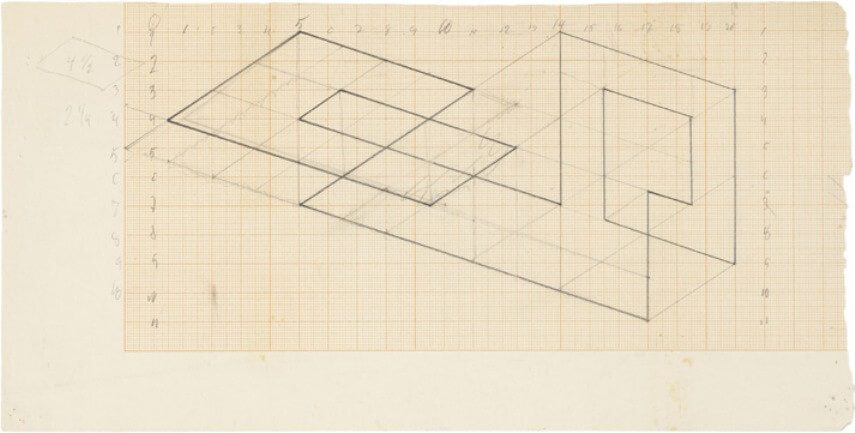

Josef Albers - Study for Tenayuca, 1940, Pencil on paper, 6 × 11 ½ in., Collection SFMOMA. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

While at the Bauhaus, Albers formulated his outlook not only on creating art, but also on teaching art. Although he personally was highly focused on technique, he realized that he would not spend his class time teaching technique. Rather, he decided he would focus on teaching a way of thinking about art. He engaged in a thoughtful, scientific approach to his art, and he believed that the most important thing to give students was a way to see the world differently than they had seen it before. His stated goal as a teacher was “to open eyes.”

When Nazi pressure closed the Bauhaus in 1933, Albers came to America and taught at the newly opened Black Mountain College in North Carolina. In 1950 he left that position and went on to head the design department at Yale. Along the way his students included several who became some of the most influential artists of the 20th Century, including Robert Rauschenberg , Willem de Kooning, Eva Hesse and Cy Twombly.

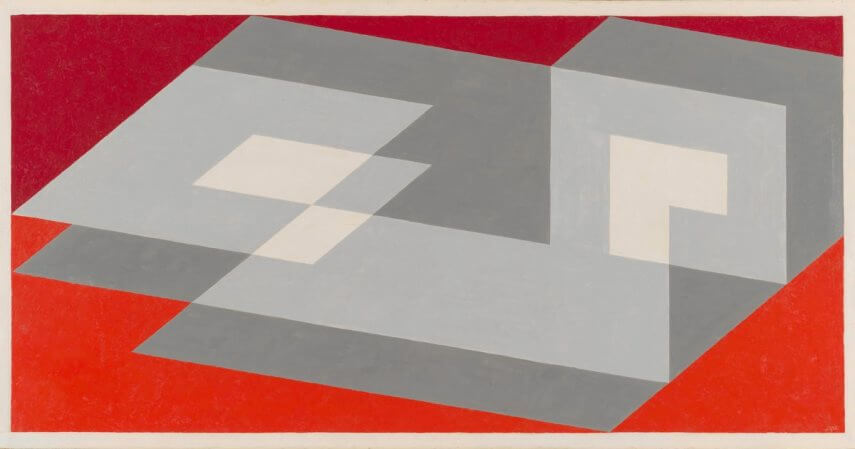

Josef Albers - Tenayuca, 1943, Oil on masonite, 22 ½ x 43 ½ in., Collection SFMOMA. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Interaction of Color

One of the criticisms many artists, critics and viewers have heaped on Albers is that his work seems impersonal. The reason for this no doubt has to do with Albers’ scientific approach to his art. For example, on the back of many of his works he writes in detail the exact colors that the piece utilizes. But there is great depth of emotion and a good deal of psychology present in Albers’ work as well. Albers was interested in the way colors interacted with each other, and the effect that interaction had on human perception. One of the key discoveries he made is that human beings are easily susceptible to illusion, something he considered easily demonstrable through his art.

In 1963, while at Yale, Albers wrote a book called The Interaction of Color, which covered in exacting detail all of his discoveries about the way colors interacted with each other. The book includes detailed lessons, experiments and graphics explaining how certain colors neutralize or alter other colors, how light affects hue, and how what he called the “normal human eye” was not able to grasp certain color phenomena due to the limitations of its perceptual capabilities. If we consider this book on a conceptual level, as with his paintings, the lessons are not so much about color as they are about the fact that humans are limited in what they can perceive, and if artists can understand those limitations they can potentially expand the perceptual range of those who encounter their work.

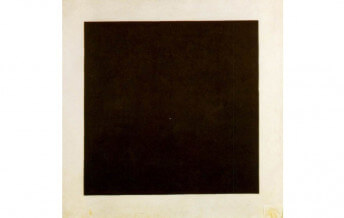

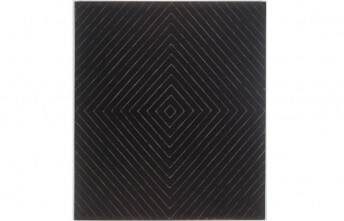

Homage to the Square

In addition to his writings on color, Albers devoted 27 years of his life to creating a series of paintings called Homage to the Square. This series demonstrated his color theory through an exploration of different colored squares. By using a single geometric form over and over, he was able to investigate the vast range of perceptual phenomena that could be achieved simply by juxtaposing various colors together within a limited range of spatial compositions.

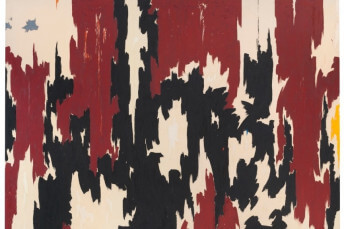

When Albers began making his Homage to the Square paintings in 1949, even artists largely ignored them. The art world at that time was dominated by monumentally sized, gestural action paintings. Albers’ paintings were so small relatively, and so controlled. They were designed. Albers once defined design as, “to plan and organize, to order, to relate and to control. In short it embraces all means opposing disorder and accident.” In a time when Abstract Expressionism was the predominant style, designed, seemingly emotionless paintings were like heresy.

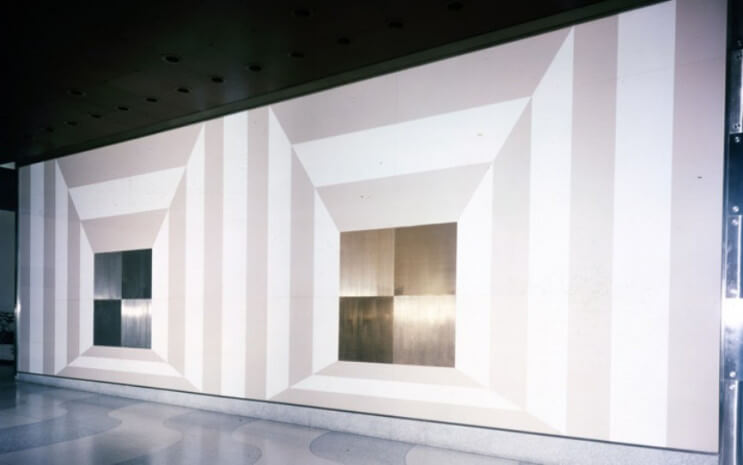

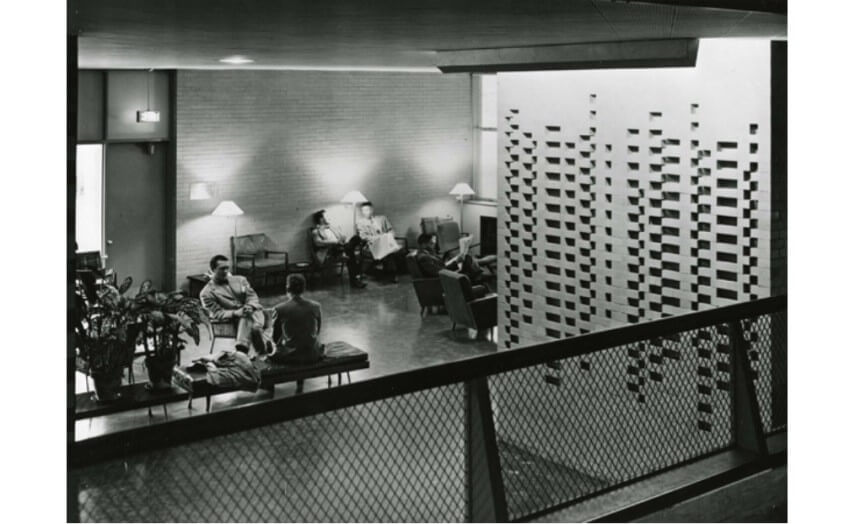

By the 1960s the art world caught up with Albers and he became as respected as an artist as he already was as an educator, writer and philosopher. Some of that respect came to him from a series of commissions he received to do large-scale public works, some in the form of architectural elements and some in the form of murals. One of the earliest of Albers architectural works was a wall he created for Harvard University’s Harkness Commons Graduate Center. His murals included works for the Time and Life Building at New York’s Rockefeller Center, Pan Am Center and the Corning Glass Building. In 1971, at age 83, Albers became the first living artist to be honored with a solo exhibition by New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Josef Albers - Brick, 1950, 71⁄2 × 8 ft, 2.3 × 2.5 m, Harkness Commons Graduate Center, Harvard University. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A Lasting Impression

Early in his own training, Albers was deeply moved by the Impressionists, especially the Pointillists , who explored the “impression” of color created when complimentary colors were placed side by side in small dots rather than actually mixing the colors ahead of time. In a poem written to a friend about the habit people had of following the crowd rather than thinking for themselves Albers once wrote: “Everyone senses his place through his neighbor.” Like an Impressionist painting viewed from afar, Albers saw society as so many individuals mixing together to form one common picture.

He devoted his life to taking a unique path, isolating his own vision and staying true to it. By studying what he learned about how individual colors affect each other when near each other, and about humans’ ability to be deceived by illusion, we can appreciate not only his artwork and his lessons about painting, but also something fundamental about ourselves.

Featured Image: Josef Albers - Portals, Time Life Building, 1961. © The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio