Abstract Sculpture - The Language of the Full and the Empty

Jul 29, 2016

Since Modernism’s earliest days, questions have been raised about the nature of, and difference between, two and three-dimensional abstract art. In the first decade of the 20th Century, Constantin Brancusi asked the basic question of what abstract sculpture was meant to convey: a subject’s image or its essence? In the next decade, Pablo Picasso proved that a sculpture didn’t need to be carved, molded or cast: it could be assembled. In the decade after that, Alexander Calder demonstrated that sculpture could move. And still decades later, in reference to his cross-disciplinary works, Donald Judd offered “Specific Objects” as an alternative for the words painting and sculpture. Though the topic could fill several books, today we offer you a brief, admittedly much pared down timeline of some of the highlights of abstract sculpture’s history.

The Father of Abstract Sculpture

Constantin Brâncusi was born in Romania in 1876 when the universe of European fine art basically consisted of painting and sculpture, and both were almost entirely figurative. Though the gradual evolution toward abstraction had begun, few professional artists had yet been bold enough to attempt pure abstraction, or even to define what exactly that meant. Brâncusi’s first experience sculpting was utterly practical, carving farm implements to use as a child laborer. Even when he eventually made it to art school he was classically trained. But when Brâncusi left Romania in 1903, ultimately arriving in Paris, he became involved in the Modernist conversation. He enthusiastically agreed with the ideas circulating about abstraction, and soon concluded that sculpture’s modern purpose was to present “not the outer form but the idea, the essence of things.”

In 1913, some of Brâncusi’s early abstract sculptures were exhibited in New York City as part of that year’s Armory Show, the exhibition largely responsible for introducing Modernist art to the US. Critics publicly ridiculed his sculpture Portrait of Mademoiselle Pogany for, among other things, looking like an egg. Thirteen years later, Brâncusi would have the last laugh at the Americans when one of his sculptures caused US Federal law to be changed. That happened when a collector purchased and attempted to ship into the US one of Brâncusi’s bird sculptures, which in no way resembled birds, but rather represented flight. Rather than exempting the abstract sculpture as art, customs officials charged the collector an import tax. The collector sued, and won, resulting in an official declaration from the US courts that something did not have to be representational in order to be considered art.

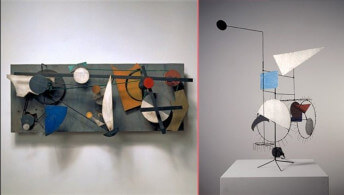

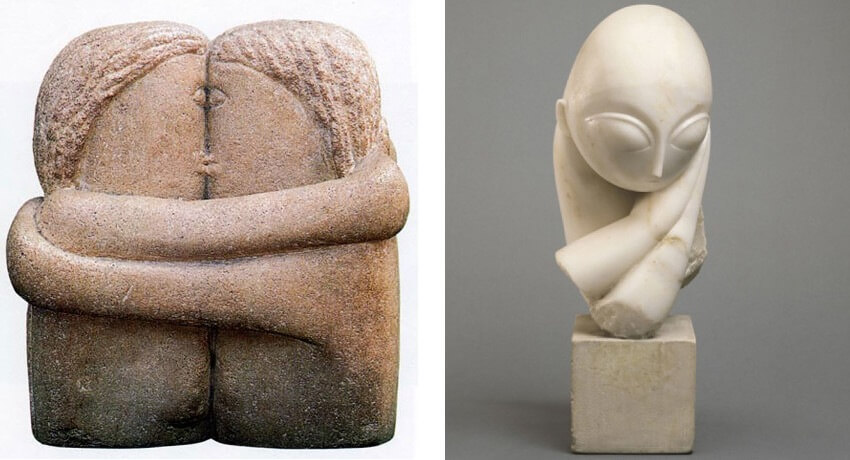

Constantin Brancusi - The Kiss, 1907 (Left) and Portrait of Mademoiselle Pogany, 1912 (Right), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, © 2018 Constantin Brancusi / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris

Constantin Brancusi - The Kiss, 1907 (Left) and Portrait of Mademoiselle Pogany, 1912 (Right), Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, © 2018 Constantin Brancusi / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY / ADAGP, Paris

Pablo Picasso and the Art of Assemblage

Pablo Picasso was another vital early pioneer in the realm of abstract sculpture, although he may not have intended to be. Around 1912, Picasso started expanding his ideas about Cubism into the three-dimensional realm. He began by making collages, which due to their layered surface and use of found materials and objects in lieu of paint already had a sort of three-dimensional quality. Then he translated the idea of collage into full three-dimensional space by assembling actual objects, especially guitars, out of materials like cardboard, wood, metal and wire.

Traditionally, sculpture resulted from either a mold, or from forming of mass like clay, or from some sort of reductive process like carving. Picasso had inadvertently challenged that tradition by creating a sculptural item through the act of assembling disparate pieces of found materials into a form. Furthermore, he blew minds by hanging this assemblage on the wall rather than setting it on a pedestal. Art viewers were baffled and even outraged by Picasso’s guitars, demanding to know whether they were paintings or sculptures. Picasso insisted they were neither, saying, “It’s nothing, it’s the guitar!” But whether he had intended to or not he had challenged the fundamental definition of sculpture, and started one of the longest lasting debates about abstract art.

Pablo Picasso - Cardboard Guitar Construction, 1913, MoMA

Pablo Picasso - Cardboard Guitar Construction, 1913, MoMA

Readymades

As revolutionary as artists such as Picasso and Brâncusi may have seemed to art viewers in their time, it’s interesting to note that 1913 is also the year that the Dadaist artist Marcel Duchamp appropriated the term “readymade” to designate works of art consisting of found objects, signed and exhibited by an artist as their work. According to Duchamp, ordinary objects could be “elevated to the dignity of a work of art by the mere choice of an artist.” In 1917, Duchamp exhibited Fountain, perhaps his most famous readymade, consisting of a urinal placed on its side and signed “R. Mutt.”

Duchamp had created Fountain for submission to the first exhibition of New York’s Society of Independent Artists, which was heralded as a completely open show of contemporary art, with no juries and no prizes. The work was bizarrely rejected from the show, causing uproar in the art community since the whole point of the exhibition was not to pass judgment on the work. The Society’s board issued a statement about Fountain that said, “it is, by no definition, a work of art.” Nonetheless, the work went on to inspire generations of creatives to come.

A copy made in 1964 of Duchamp's original 1917 Fountain

Faktura and Tektonika

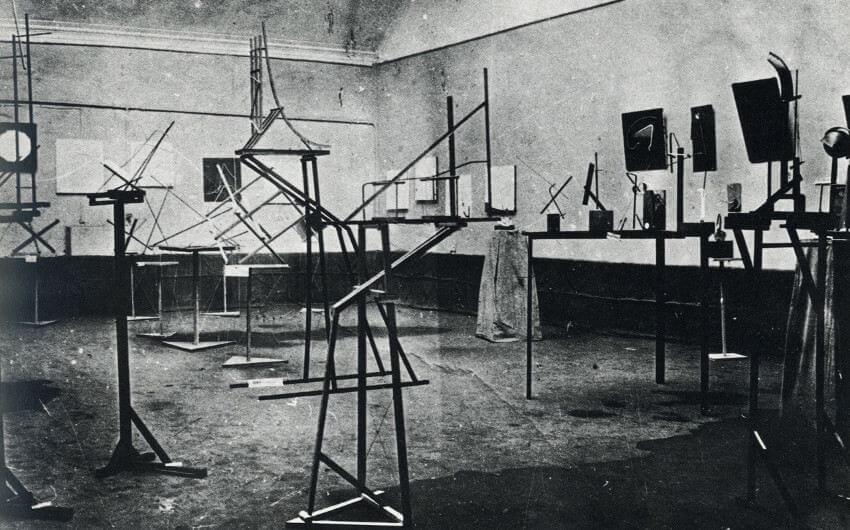

In 1921, a group of artists called The First Working Group of Constructivists emerged in Russia. The goal of their movement, which they called Constructivism, was to create a pure art based on formal, geometric, abstract principals that would actively involve the viewer. The sculptural principals of Constructivism were broken down into two separate elements: faktura referred to a sculpture’s material qualities, and tektonika referred to a sculpture’s presence in three-dimensional space.

The Constructivists believed that sculpture needed no subject whatsoever, and could take on entirely abstract properties. All that mattered to them was the exploration of materiality and space. They were specifically conscious of the way an object occupied the exhibition space, as well as how it interacted with the space between it and the viewer. Constructivist sculpture helped define the notions that a sculpture could contain and define space in addition to simply occupying space, and that space itself could become an important element of the work.

The first Constructivist Exhibition, 1921

Drawing in Space

By the late 1920s, the Modernist abstract sculptural language included dimensional reliefs, found objects, geometric and figurative abstraction and the notion of the fullness and the emptiness of physical space. The Italian Futurists had even attempted to use sculpture to demonstrate movement, or Dynamism, in such pieces as Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (covered in more detail here. But the honor of introducing actual movement into sculpture, creating a new arena called Kinetic Sculpture, goes to Alexander Calder.

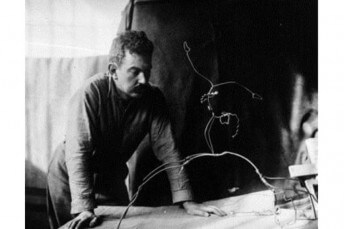

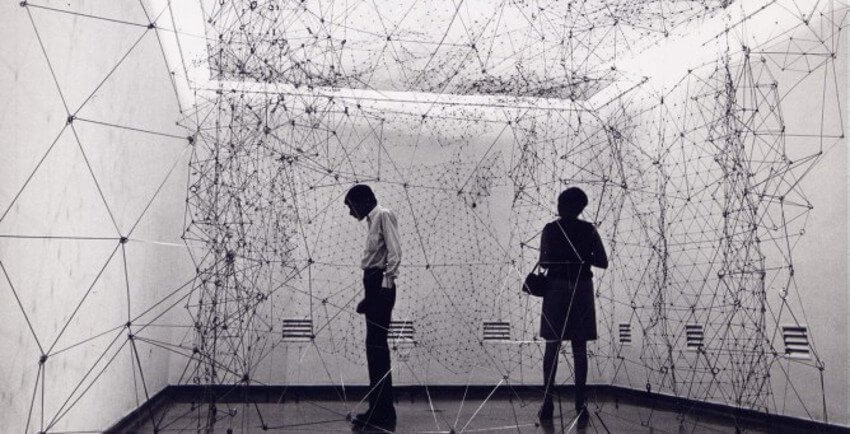

Calder was trained as a mechanical engineer, and only later attended art school. After graduating, he began making mechanical toys, eventually designing an entire mechanical circus. Around 1929, he began making delicate, playful wire sculptures, which he described as “drawing in space.” In 1930, when he added moving parts to his wire sculptures, Marcel Duchamp called these artworks “mobiles.” Calder’s kinetic mobiles have now become the most instantly recognizable part of his oeuvre, and went on to inspire artists like Jean Tinguely, creator of Metamechanics. They also influenced perhaps the most prolific Modernist master of “drawing in space,” the Venezuelan artist Gego, who took the concept to elaborate extremes in the 1960s.

Gego, spatial wire construction, partial installation view

Gego, spatial wire construction, partial installation view

Combines and Accumulations

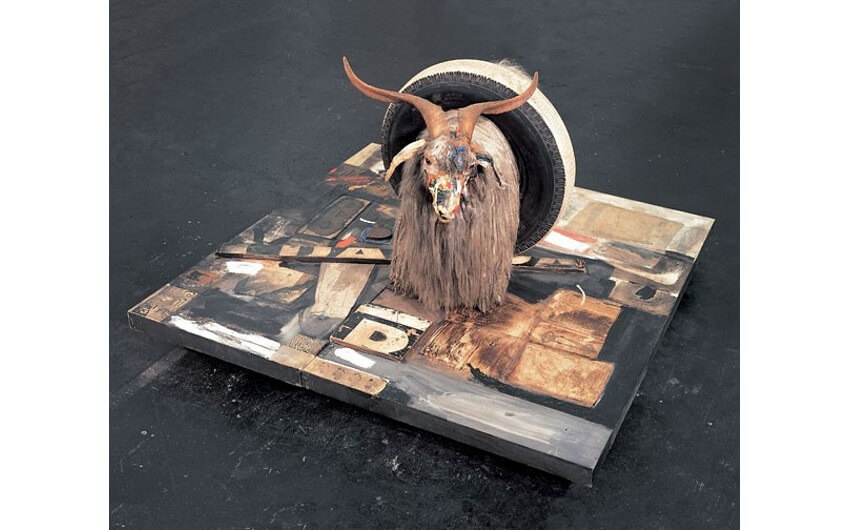

In the 1950’s, conceptual artists ran with the ideas pioneered by Picasso and Duchamp. The concept of the found object became ubiquitous as large metropolitan cities became overburdened with refuse and the mass production and consumption of industrial products reached new heights. The multi-disciplinary artist Robert Rauschenberg incorporated the fundamentals of Picasso’s collages and assemblages with Duchamp’s concepts about found objects and artist’s choices in order to create what became his signature contribution to abstract sculpture. He called them “Combines,” and they were essentially sculptural assemblages made from assorted trash, detritus and industrial products, thoughtfully combined into a single mass by the artist.

Robert Rauschenberg - Monogram, Freestanding combine, 1955, © 2018 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Robert Rauschenberg - Monogram, Freestanding combine, 1955, © 2018 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation

Around the same time, the Conceptual Artist Arman, one of the founding members of the Nouveau Realists, used Duchamp’s idea of the Readymade as a jumping off point for a series of sculptural works that he called Accumulations. For these works, Arman collected multiples of the same readymade objects and welded them together into a sculptural mass. By utilizing products in this way, he re-contextualized the idea of a readymade product, using it instead as an abstract form, removing its former meaning and transforming it into something symbolic and subjective.

Arman - Accumulation Renault No.106, 1967, © Arman

Arman - Accumulation Renault No.106, 1967, © Arman

Materials and Process

By the 1960s, sculptors were focusing more and more on the pure formal aspects of their works. As a sort of rejection of the emotion and drama of their predecessors, sculptors like Eva Hesse and Donald Judd focused on the raw materials that went into their work and the processes by which their objects were made. Eva Hesse pioneered working with often-toxic industrial materials such as latex and fiberglass.

Eva Hesse - Repetition Nineteen III, 1968. Fiberglass and polyester resin, nineteen units, Each 19 to 20 1/4" (48 to 51 cm) x 11 to 12 3/4" (27.8 to 32.2 cm) in diameter. MoMA Collection. Gift of Charles and Anita Blatt. © 2018 Estate of Eva Hesse. Galerie Hauser & Wirth, Zurich

Eva Hesse - Repetition Nineteen III, 1968. Fiberglass and polyester resin, nineteen units, Each 19 to 20 1/4" (48 to 51 cm) x 11 to 12 3/4" (27.8 to 32.2 cm) in diameter. MoMA Collection. Gift of Charles and Anita Blatt. © 2018 Estate of Eva Hesse. Galerie Hauser & Wirth, Zurich

Unlike Hesse, whose technique and individuality was prominently featured in her sculptural forms, Donald Judd endeavored to completely remove any evidence of the artist’s hand. He worked to create what he called Specific Objects, objects that transcended the definitions of two and three-dimensional art, and that used industrial processes and materials, and were usually fabricated by machines or by workers other than the artist.

Donald Judd - Untitled, 1973, brass and blue Plexiglas, © Donald Judd

Donald Judd - Untitled, 1973, brass and blue Plexiglas, © Donald Judd

Contemporary Omni-Disciplinary Art

Thanks to the advances Modernist sculptors have made in the past 100+ years, today is a time of amazing openness in abstract art. So much contemporary practice is omni-disciplinary, resulting in exciting, polymorphic aesthetic phenomena. The works of many contemporary abstract artists have such unique presence that they defy simple labels like “painting,” “sculpture,” or “installation.” The Modernist pioneers of abstract sculpture are, to a large degree, responsible for much of the openness and freedom contemporary artists enjoy, and for the myriad ways we can enjoy their aesthetic interpretations of our world.

Featured image: Alexander Calder - Blue Feather, 1948, kinetic wire sculpture, © Calder Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio