The Full and the Empty in Henry Moore Sculptures

Aug 18, 2016

A human body is more than a single mass; it is an accumulation of smaller masses. And each body is also part of a larger mass: that of humanity. And humanity is part of some larger mass still: that of the world. The sculptor Henry Moore put it best when he said, “The whole of nature is an endless demonstration of shape and form.” Moore devoted his career to an exploration of shape and form. Despite how academic that sounds, Henry Moore sculptures are not simply intellectual objects. Nor are they solely objects of beauty. They transcend both intellectualism and aesthetics to connect viewers to something deeper. As a figurative artist first and then as an abstractionist, Moore created work based upon the relationship the human body shares with the larger natural world. His sculptures express the ideas that humanity is part of nature and that through our senses we can become connected to something timeless and universal.

Henry Moore Sculptures - Material Truths

When a sculptor talks about material truth, it is a reference to how well an object represents the qualities of the resource from which it is made. Walnut has a different material truth than marble, which has a different material truth than alabaster, and so on. Henry Moore was a believer in the power of material truth. He rejected the idea that sculptors should make their works from molds or casts. He advocated for direct carving, since it left behind marks that revealed the object’s physical nature. Direct carving was not widely accepted in Moore’s time, even though some other influential sculptors also embraced the idea. But for Moore it was not just a theory; it was his nature.

Henry Moore - Reclining Figure relief at the Underground Building at St James’s, 1928. © The Henry Moore Foundation.

Moore was one of nine children born to a working class family in Castleford, a coalmining town in Yorkshire, in England. His parents struggled and sacrificed to send their kids to school so they wouldn’t have to work with their hands. At age 11 after encountering the work of Michelangelo, Henry disappointed them by deciding he would be a sculptor. Unable to afford to go directly to university, Henry fought in a Civil Service Rifles regiment in World War I and was injured in a gas attack. By the time he could afford art school after the war, he was thoroughly shaped by his own material truths: he was born for hard work and doing things by hand. Direct carving not only brought out the character of his materials, it brought out his character as well.

Henry Moore - The UNESCO Reclining Figure, 1958. © The Henry Moore Foundation.

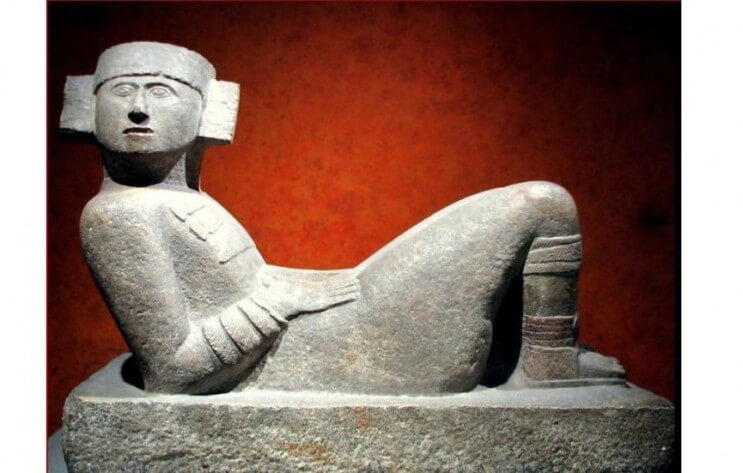

The Marriage of Chac-mool and Cézanne

In his late 20s, in Paris, Moore encountered an aesthetic object that changed him in a profound and meaningful way. It was a Chac-mool, a Pre-Columbian Aztec sculpture of a reclining human figure. The sculpture’s posture evokes human figures sculpted by classical sculptors such as Michelangelo, but it occurred independently of such influences, and a world away. The figure’s demeanor and humanity inspired Moore, and he embraced the form as something universal with which he could work.

Henry Moore - Four-Piece Composition: Reclining Figure. © The Henry Moore Foundation.

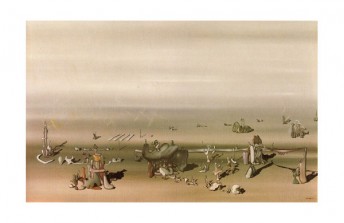

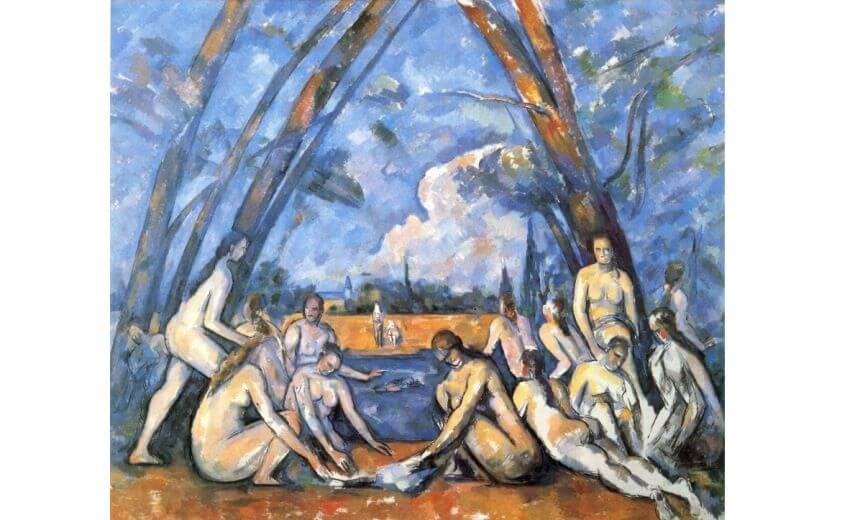

Moore married the Chac-mool’s essence with figuration inspired by one of his most beloved paintings, Cézanne’s The Bathers. The result was an iconic, Modernist sculptural form he called a “reclining figure.” He explored reclining figures throughout his career, returning to it over and over again as the basis for discoveries about volume and space. Today, Moore’s reclining figures can be found the world over, in sculpture parks, nature spaces and museums on six continents. His first public commission was a reclining figure carved in relief on the Underground Building at St James’s in London. His most famous graces the UNESCO headquarters in Paris.

Cézanne - The Bathers, 1898-1905, Oil on canvas, 210.5 cm × 250.8 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, United States

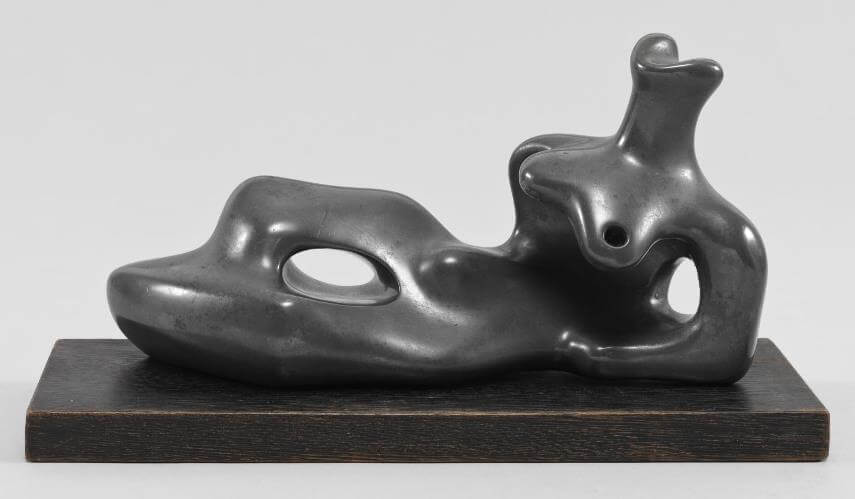

Reduction of Form

The majority of Moore’s Reclining Figures were abstract. He continually reduced the shape of the human figure to its essential elements then abstracted them to resemble shapes found in nature. His biomorphic, abstracted reclining figures seemed analogical with the natural landscape, inspiring many to find humanistic messages in them. Though he preferred to talk as little as possible about his work’s meaning, this interpretation fits in well with Moore’s philosophy of the interconnectedness of art, humanity and nature.

Henry Moore - Reclining Figure. © The Henry Moore Foundation.

In addition to abstracting the reclining figure, Moore also dissected it. He pierced holes in the figures, remarking, “The first hole made through a piece of stone is a revelation.” He also challenged perceptions of volume and space by pulling the figures apart into collections of loosely affiliated forms that, separately, were abstracted, but when placed together hinted at a human form.

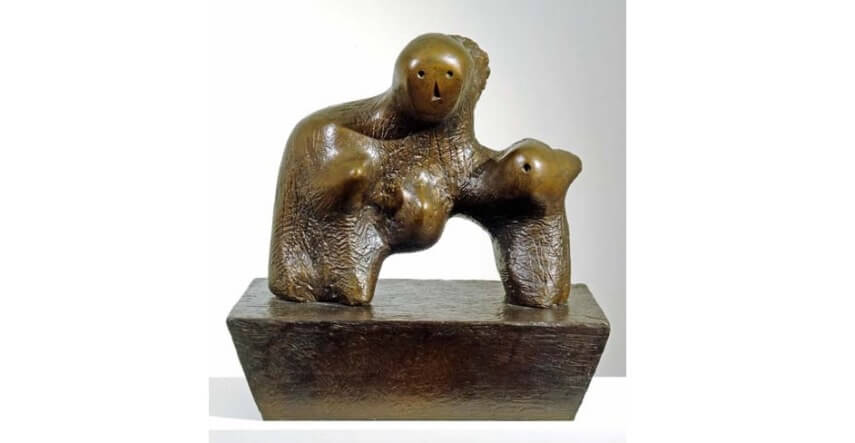

Henry Moore - Mother and Child, 1959. © The Henry Moore Foundation.

Protect the Inner Form

At the height of Moore’s productivity World War II broke out and he was enlisted as a war artist. He created a series of drawings documenting citizens huddled in masses in the underground during bombing raids. The drawings capture the fear as human forms cocoon themselves in a shelter, and then cocoon each other in piles of huddled bodies. After the war this idea, of one form being protected within another, manifested everywhere in his sculptures. He produced multiple works titled Mother and Child, some evoking a child within the form of the mother, and others showing two forms separate, but huddling together.

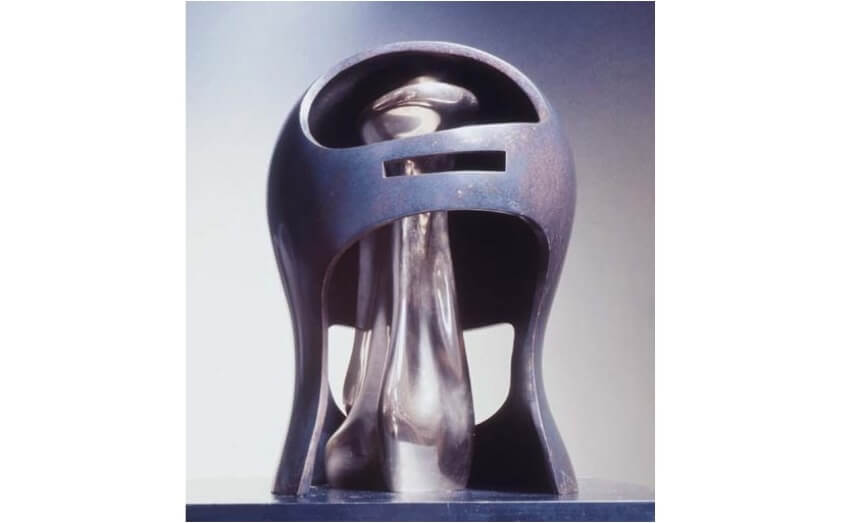

Henry Moore - Helmet Head No.5, 1966. © The Henry Moore Foundation.

He also explored this idea with a series called Helmet Head, creating helmet forms that sometimes held nothing but empty space, and other times contained secondary forms protected within them. These protective sculptures use mass and the space around it as their subject. In a formal sense they examine the fullness and the emptiness of space. In a humanist sense they demonstrate our most basic reality: the need for safety.

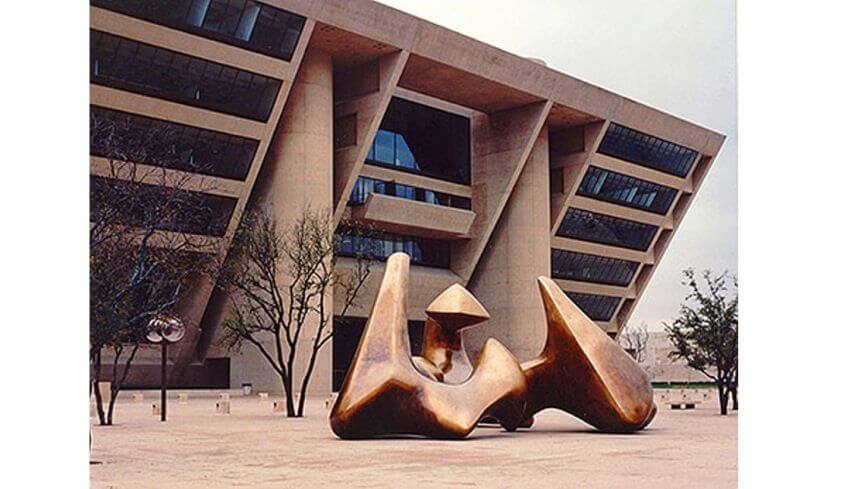

Henry Moore - Three Forms Vertebrae, 1978-79, outside City Hall, Dallas, TX. © The Henry Moore Foundation.

Exercises in Form

In 1947 a contemporary of Moore’s, the French author Raymond Queneau, wrote a book called “Exercises in Style,” in which he told the same brief anecdote in 99 different literary styles. It could be said that Henry Moore took a similar approach to his career. He pursued a few subjects in a multitude of different ways, focusing on a small range of concerns, such as shape, form and the way they interact with space. But if that were all he did, he wouldn’t have made such a legendary mark on 20th Century abstract art.

Moore’s big idea was always humanity; a point most evident when considering his public sculptures, which today exist in 38 countries. Moore intended for them to be touched, climbed on, explored and inhabited. They exist for all of our senses. Moore once said, “Our knowledge of shape and form remains, in general, a mixture of visual and of tactile experiences... A child learns about roundness from handling a ball far more than from looking at it.” From Moore’s work we do learn about roundness, and about materiality, form, space and many other formal, tactile things. But we also learn something more important: something about our interconnectedness with the landscape, with each other, with nature and with ourselves.

Featured Image: The Chac-mool, a sculptural figure found throughout prehistoric Mexico

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio