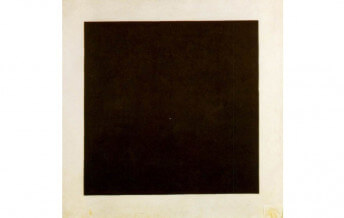

The Evolution of Style in Piet Mondrian Artwork

Sep 18, 2016

Many artists strive to express what is universal. But what does that mean, universal? To Piet Mondrian it meant spiritual: but not dogmatic, or religious. Rather, Mondrian used the word spiritual to refer to the underlying equilibrium that connects all beings. The prolific body of Piet Mondrian artwork we can look back on today tells the story of an artist who underwent an aesthetic evolution, from objective, figurative representation to pure abstraction. By tracing that evolution through its various stages, we can follow Mondrian along his personal philosophical and artistic journey, through which he sought to understand the universal essence of humanity and to perfectly express it through abstract art.

Young Piet Mondrian

Like many abstract artists, Piet Mondrian began his artistic training by learning how to accurately copy the natural world. From a young age he learned drawing from his father, and from his uncle, a professional artist, he learned how to paint. At age 20, Mondrian enrolled at Amsterdam’s Royal Academy of Visual Arts, where he continued to receive an education in classical technique. His became adept at copying the work of the masters. By the time he graduated he was an expert at technical drawing, and he had developed the analytical skills necessary to perfectly copy imagery from real life.

But after graduating from school, Mondrian became exposed to the Post Impressionists and his vision of what he could achieve through painting began to evolve. He became inspired by the various ways these artists attempted to express something more real, such as by intensifying the quality of light or the experience of color, than could otherwise be expressed through direct mimicry. Mondrian explored the techniques of artists like Georges Seurat and Paul Cézanne and began a process of breaking away from representational painting. Through abstraction he sought ways of expressing the underlying truth of the natural world.

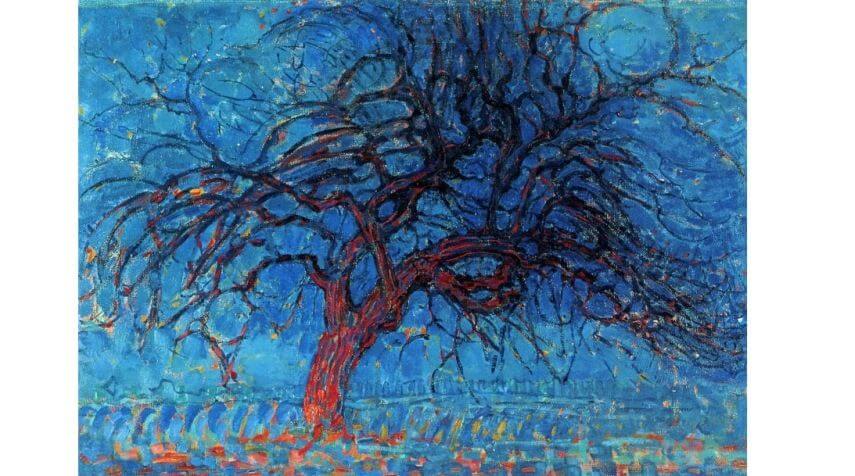

Piet Mondrian - Evening: Red Tree, 1908-1910. 99 x 70 cm. Gemeentemuseum den Haag, Hague, Netherlands

Reflections on the Essential

To begin with, Mondrian eliminated the need to paint in realistic colors, and abandoned the need to perfectly imitate form. He tended to work in series, painting the same image in multiple, subtly different ways. For example, in a series of paintings he began around 1905, he painted the same farmhouse in several different styles, changing the colors, changing his portrayal of form, and changing his use of line. In each image there are similarities, such as that the farmhouse is reflected in a nearby body of water, and yet in each painting the mood of the paintings is different. Despite the different moods though, each possesses a sense of natural, harmonious balance.

Through the process of working in series, Mondrian was able to apply his analytical skills to the various outcomes at which he arrived. He became adept at understanding the various ways that abstraction could affect the emotional and aesthetic qualities of his paintings. He also became more aware of the underlying, universal patterns that exist in the natural world and the ways that humans interpret them as being aesthetically pleasing. As he said; “If the universal is the essential, then it is the basis of all life and art. Recognizing and uniting with the universal therefore gives us the greatest aesthetic satisfaction, the greatest emotion of beauty.”

Piet Mondrian -The Flowering Apple Tree, 1912

Spirit and Place

In 1908, Mondrian became a member of the Theosophical Society, an organization that also counted among its membership artists such as Wassily Kandinsky and Theo van Doesburg. The Theosophists sought ways of connecting with and understanding the ancient spiritual wisdom of the universe. Mondrian was convinced that art was directly connected with the higher questions of life and that through art the harmonious essence of existence could be communicated. Influenced by the Theosophists spiritual quest for universal wisdom, Mondrian sought to reduce his approach, to become simpler, to take things back to their basic nature. This manifested in his art in various ways such as more pared down forms and more pure use of color, such as in Evening: Red Tree, from 1908.

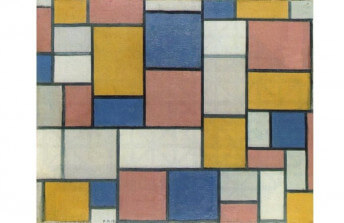

His process of paring down his visual language reached its most important turning point in 1912, when Mondrian moved to Paris. There the avant-garde was dominated by the ideas of Analytic Cubism. The way Cubism confronted surface and planes and the way it limited its color palette encourage Mondrian to fully commit himself to abstraction. Though he had no interest in capturing a sense of movement or four-dimensionality, he experimented with the Cubist use of planes and adopted their muted and simplified use of color.

Piet Mondrian - The Grey Tree, 1911. Oil on canvas. 78.50 cm × 107.5 cm (30.9 in × 42.3 in). Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, The Hague

Back Home Again

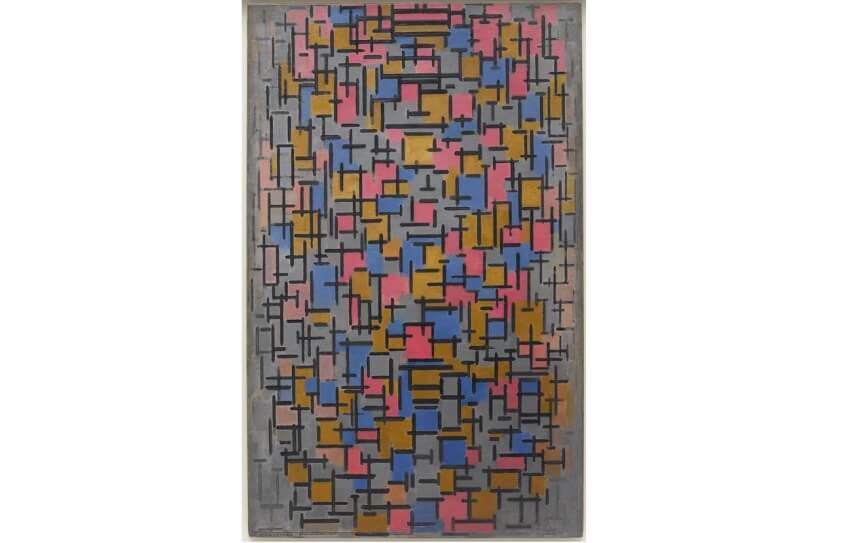

In 1914, Mondrian left Paris for what was supposed to be a brief visit home to see his father. The outbreak of World War I, however, kept him in the Netherlands for the next five years. Although removed from the avant-garde of Paris during this time, Mondrian continued his quest to distill his abstract visual language down to express the harmonious essence of the universal. Serendipitously, also in the Netherlands at this same time were two artists whose similar aesthetic quest would solidify the iconic style Mondrian would eventually develop. One of those artists, Bart van der Leck, convinced Mondrian that his use of color was still representational, and that he should gravitate toward pure, primary colors.

The other artist was Theo van Doesburg who influenced Mondrian to flatten his images in order to eliminate of volume, and to eliminate everything but line and color. Said Mondrian of this revelation; “I came to the destruction of volume by the use of the plane. This I accomplished by means of lines cutting the planes. But still, the plane remained too intact. So I came to making only lines and brought the colour within the lines. Now the only problem was to destroy these lines also through mutual oppositions.”

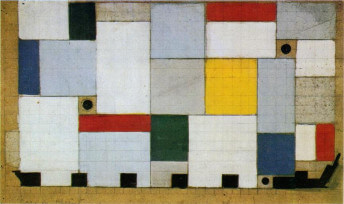

Piet Mondrian - Composition, 1916, Oil on canvas, with wood, 47 1/4 x 29 3/4 in (120 x 75.6 cm), Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York Solomon R. Guggenheim Founding Collection, © 2007 Mondrian/Holtzman Trust

Evolving Toward Harmony

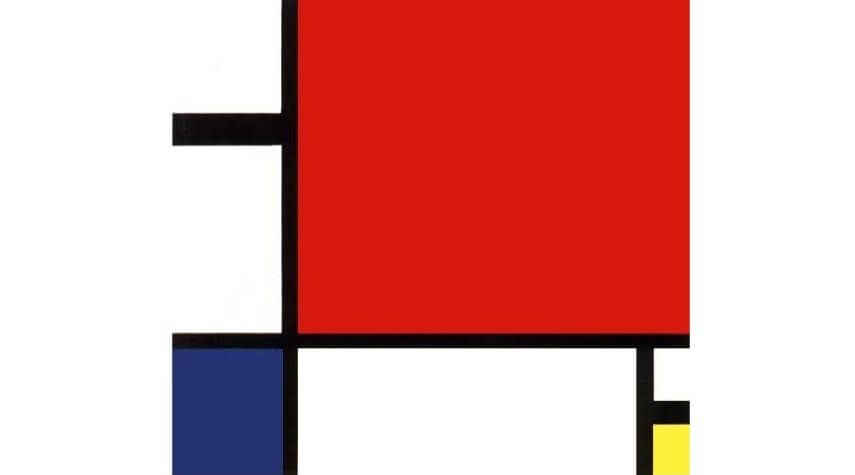

It was together with Theo van Doesburg and Bart van der Leck during World War I that Mondrian successfully developed what we now think of as his individualized style. They called their approach De Stijl, Dutch for the Style. It successfully achieved pure abstraction, free from all figurative references. Mondrian even eliminated his use of referential titles, naming his De Stijl paintings compositions followed only by specific descriptions of their colors.

In his early De Stijl works, Mondrian used fields of color in multiple hues, and used horizontal, vertical and diagonal lines. Quickly though he eliminated the diagonal lines, preferring to use only horizontal and vertical lines, which he considered representative of the balancing forces of nature, such as action and inaction, or motion and stillness. Van Doesburg, however, maintained the use of diagonal lines, considering Mondrian’s approach too limiting and dogmatic. That slight difference caused the two artists to end their association, and led to the end of De Stijl.

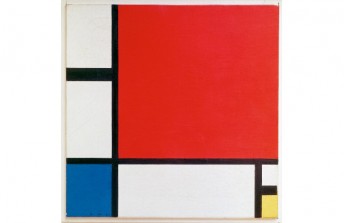

Piet Mondrian - Composition II in Red, Blue, and Yellow, 1929. Oil and paper on canvas. 59,5 cm × 59,5 cm (23.4 in × 23.4 in). National Museum, Belgrade, Serbia

Expressing the Universal

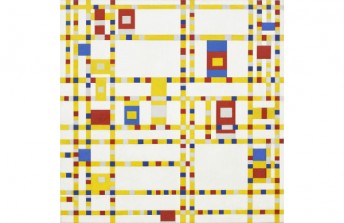

After Van Doesburg and Mondrian split, they each renamed their individual interpretations of De Stijl. Van Doesburg called his new style Elementarism and Mondrian called his new style Neo-Plasticism. In addition to only using horizontal and vertical lines, Neo-Plasticism included only the primary colors of red, blue and yellow, and the primary values of black, white and gray. The Plastic in New-Plasticism came from the history of referring to all arts that attempted to represent three-dimensional reality as the plastic arts. Neo-Plasticism communicated that Mondrian believed his fully abstracted style portrayed in the simplest and most direct way what is essential, real and universal.

There are multiple views on abstraction through reduction. Some believe it hides what is real. Others believe it reveals what is essential. Some consider it to be the same as generalization, and therefore interpret it as inherently incomplete. Through Neo-Plasticism, Mondrian presented a confident point of view on this topic. Mondrian believed that reduction was essential in order for humans to achieve our highest state of existence. He believed that complications are manifestations of the basest elements of human nature, and that petty details lead us to focus on our vast individual differences, preventing us from achieving a sense of universality. By seeking what is most simple, most essential and most relatable to all he attempted to create a new and completely abstract visual language, one that could be relatable to everyone who encountered it and could connect us all in a profound and universal way.

Featured Image: Piet Mondrian - Truncated View of the Broekzijder Mill on the Gein, Wings Facing West, 1902. Oil on canvas on cardboard. 30.2 x 38.1 cm. MOMA Collection

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio