Lee Krasner and Her Impressive Oeuvre

Oct 12, 2016

Some artists focus so intently on one particular style that almost any art lover can easily describe typical examples of their works. Others, however, purposefully and constantly evolve their style, refusing to be limited by one aesthetic approach. Lee Krasner epitomized the latter. To describe typical Lee Krasner paintings would be impossible, because her work was never typical. Multiple times over the course of her career Krasner completely redirected her approach to painting. Although she is normally associated with the Abstract Expressionists, she began her career as a classical realist painter. She also worked as a mural painter for the Works Progress Administration, and spent years experimenting variously with collage, biomorphic abstraction, hard edge abstraction, small-scale works inspired by her Jewish heritage and large-scale works informed by her personal life. Even after suffering a brain aneurism she kept reinventing her work for more than two more decades. So diverse and ingenious is her oeuvre that Lee Krasner is regarded today as embodying of the spirit of the 20th Century American avant-garde.

Brooklyn Born

Lee Krasner entered the world in Brooklyn in 1908, the first member of her family to be born on American soil. She knew at a young age that she wanted to be a painter. But in the early decades of the 1900s there were not many opportunities for young women who aspired to be professional artists. Those women who did want to study art were encouraged to go into teaching. There was only one high school in New York, the Washington Irving High School for Girls, which even allowed females to major in art classes. Lee Krasner applied and was accepted to that school.

After high school, Krasner did indeed earn her teaching certificate. But afterward, rather than going into teaching, she found work as a waitress and continued taking classes in painting. She mastered classical technique at the National Academy of Design and studied how to paint the human form at the Art Students League of New York. She was so talented that in 1935 she earned a coveted position as a mural painter with the Works Progress Administration, a rarity for any artist, let alone a female artist. The job was to copy figurative mural designs made by other artists. Krasner did not consider it ideal, as she would have preferred to paint her own designs, but it earned her a living during the depression and expanded her education.

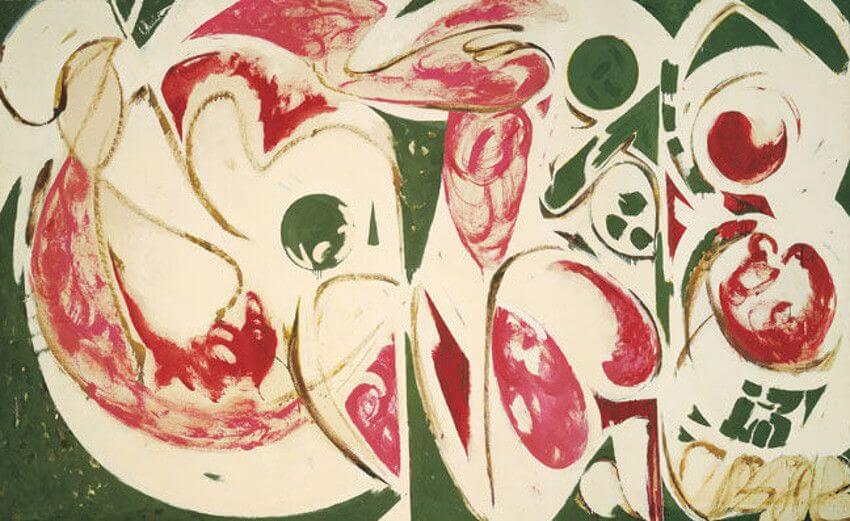

Lee Krasner - Gaea, 1966. Oil on canvas. 175.3 x 318.8 cm. Museum of Modern Art Collection. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lee Krasner - Gaea, 1966. Oil on canvas. 175.3 x 318.8 cm. Museum of Modern Art Collection. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

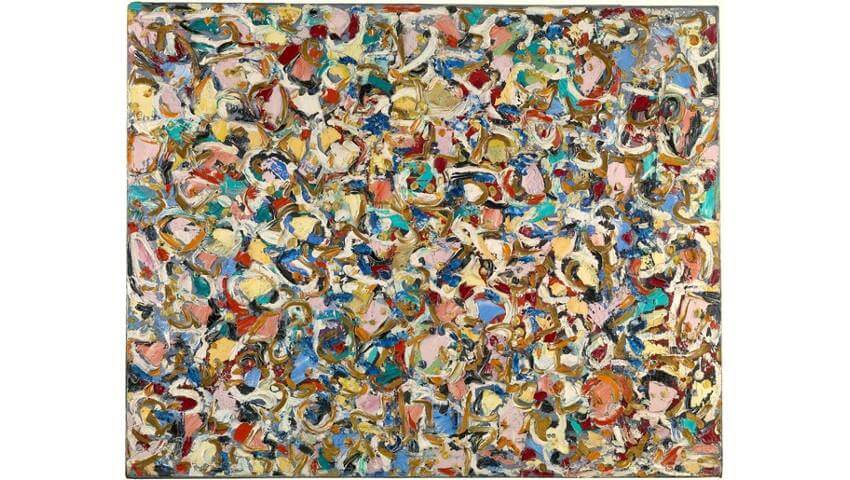

All Over Painting

In 1937, two years into her position at the WPA, Lee Krasner initiated the first major evolution in her work. She enrolled in classes with Hans Hofmann, a revered German painter and educator known for espousing Modernism and abstraction. With guidance from Hofmann, Krasner learned the concepts of Cubism, Neo-Cubism, Fauvism, collage and many other early Modernist tendencies. She put these ideas into practice in the development of what has come to be called her All Over style, an approach to painting that covered the entire surface of her works with abstract motifs evocative of nature.

Krasner ended her classes with Hans Hofmann in 1940. Then in 1941, she started a romantic relationship with the painter Jackson Pollock. When she first encountered the work Pollock was making at that time, which was driven by instinct, she immediately re-evaluated her own process. Though her work had become abstract, she was still working from real life. Inspired by Pollock she exuberantly pursued a quest to connect with her authentic, unconscious self, and to express her emotions on the canvas.

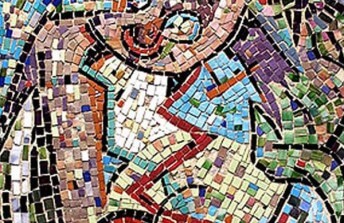

Lee Krasner - Mosaic Collage, 1939. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lee Krasner - Mosaic Collage, 1939. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Little Imageseries

In her quest for her subconscious self, Krasner turned to her roots. Her family had emigrated from what is now Ukraine. Their Russian Jewish heritage was informed by the kabala, an ancient, symbolic method of interpreting the Bible. Drawing on symbolic concept of the kabala, Krasner developed her own, intuitive, symbolic visual language; incorporating it into a series of paintings she called the Little Imageseries.

The name for this body of work likely derived from the idea that each painting seems to be composed of innumerable little images representing an abstract vocabulary without definite meaning. Or the name also could have derived from the change she experienced in her environment around the same time this series began. That change came about when Krasner and Pollock moved out of the city to a property on Long Island. Pollock took over the barn for his large-scale works. Krasner adopted an upstairs studio in the house, which was more intimate in scale, and adapted her work in conversation with the space.

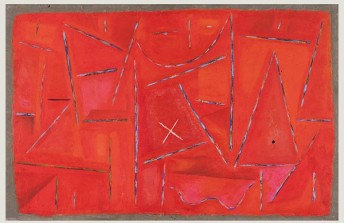

Lee Krasner - Noon, 1947, from the Little Imageseries. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lee Krasner - Noon, 1947, from the Little Imageseries. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Cut Up Collages

The next major aesthetic shift for Lee Krasner came in the early 1950s, when, according to legend, she became frustrated with the quality of several of her works and began shredding the canvases. In her earlier days studying with Hans Hofmann, Krasner had become an avid fan of Matisse, and had experimented with collage. Inspired by Matisse and his cutouts, she started using her shredded paintings as raw materials for a body of powerful, emotive collages, transforming the shreds of her failures into a radical new direction in her oeuvre.

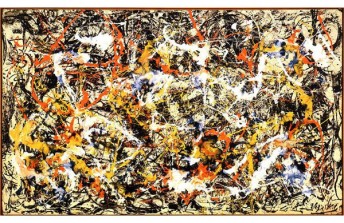

During this time in her life, there were also many other frustrations for Krasner, besides those related to her work. Her husband, Jackson Pollock, was an alcoholic and a philander, and had become quickly famous for his own unique style of action painting. In 1956, while Krasner was in Europe for the summer, Pollock died in an alcohol-fueled car wreck while drinking and driving with his mistress and a friend.

Lee Krasner - City Verticals, 1953 (Left) / Lee Krasner - Burning Candles, 1955 (Right), two canvas collages. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lee Krasner - City Verticals, 1953 (Left) / Lee Krasner - Burning Candles, 1955 (Right), two canvas collages. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Cycles of Life

Already, before Pollock died, Krasner had begun to change direction yet again in her work. She had started painting lush, biomorphic compositions of abstract, natural forms. Upon her return from Europe she further explored this motif, allowing her works to also grow in size, perhaps due to the availability of more space in which to work. Grand, sweeping gestures and simplified color palettes appeared in her compositions, and the chaos and frustration in her previous efforts gave way to a wider view of the processes of the natural world.

For six years following the death of her husband Krasner pursued this emotively powerful new style. The names she gave these series of works seemed to be connected to the cycles of life, and were perhaps symbolic of, or guided by, her grief and recovery. The first of these series, Earth Green, featured a natural color palette of greens, red, white and tans. The next series, Night Journeys, contained darker, more brooding imagery. This phase in her career came to an abrupt end in 1962 when Krasner suffered a brain aneurism that halted her work for several years.

Lee Krasner - The Sun Woman II, 1958, part of the Earth Green Series. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lee Krasner - The Sun Woman II, 1958, part of the Earth Green Series. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Hard Lines

After recovering from her aneurism, Krasner picked up where she had left off, exploring organic forms and compositions. Then in the early 1970s, she abruptly took her work in yet another new direction. She began painting flattened, hard-edged abstractions that seemed almost geometric in their visual language. Her color palette became more pure as well, resulting in paintings that feel bright, direct and optimistic.

Other aesthetic tendencies that her contemporaries were pursuing at the time possibly inspired this new direction for Krasner. Color Field painting had gained support among many Abstract Expressionists, and Minimalism was actively dominating the art scene as a reaction against the emotion and drama of the previous generation. But even though there are elements of both of these styles in the hard edge works Krasner painted in the 1970s, her expression of their sentiments is entirely unique.

Lee Krasner - Sundial, 1972. Oil on linen. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Lee Krasner - Sundial, 1972. Oil on linen. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Legacy of Lee Krasner

In 1983, Lee Krasner received the honor of her first career retrospective. It opened in Houston, Texas, at the Museum of Fine Arts. Krasner was too ill to attend the show, but as a Brooklyn native she was looking forward to the day when the exhibition would travel to her hometown. She died, however, in June of 1984, just six months before her retrospective opened at the New York MoMA. The press release for the MoMA show said, “Krasner continued to paint until shortly before her death last June, and her work to the end bespeaks unceasing exploration.”

What is truly extraordinary about the experimental nature of her career is that throughout all of her changes, Lee Krasner maintained a distinct, individual aesthetic voice. Elements of the visual language she used in her earliest works reverberate throughout her oeuvre despite a multitude of evolutions along the way. Her last works speak in fluid conversation with her earliest efforts. This is a powerful testament to the place Krasner holds in the American Modernist tradition. Her oeuvre is indicative of a radically creative mind, and speaks to the manifestation of the vanguard within her.

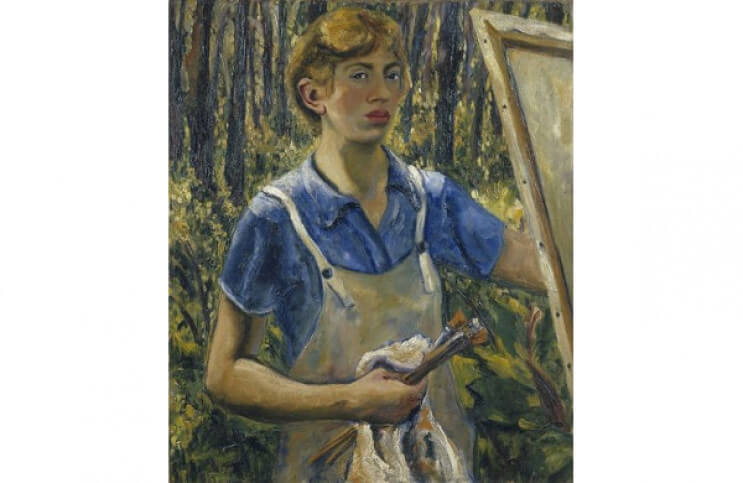

Featured image: Lee Krasner - Self-Portrait, 1930. Oil on linen. 76.5 × 63.8 cm. © 2018 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio