The Role of Biomorphic Shapes in Abstract Art

Oct 19, 2016

Biomorphism comes from the Greek words bio, meaning life, and morphe, meaning form. It does not, however, mean life form. Rather, it means the tendency to exhibit the appearance or qualities of a living thing. Though it sounds scientific, the earliest use of the term was to describe biomorphic art in the Cubism and Abstract Art exhibition of 1936 at MoMA. Written by Alfred H. Barr, the catalogue for that exhibition defined biomorphism as, “Curvilinear rather than rectilinear, decorative rather than structural and romantic rather than classical in its exaltation of mystical, the spontaneous and the irrational.” Barr coined the term to explain to viewers the nature of a certain type of abstraction that had been showing up in modern art since the early part of the 20th Century. Biomorphic abstraction incorporates a visual language based on biomorphic shapes—bulbous, lush, sumptuous looking forms—that are neither representative nor geometric, but that are uncannily familiar; people recognize them and connect with them on a primal level, though they have never seen them before.

The Roots of Biomorphism

A French philosopher named Henri Bergson first expressed the concepts underlying biomorphism in the early 1900s. At that time the prevailing attitude of the intellectual class was that reason and science were the best, if not only ways of understanding the real world. A particularly popular way of looking at the world was from a teleological perspective. Teleology states that everything has two types of purposes: natural, inborn, or intrinsic purposes, and unnatural, imposed, or extrinsic purposes. For example, the intrinsic purpose of a flower bulb would be to grow into a flower. The extrinsic purpose of a flower bulb would be to create revenue for the owner of a flower bulb store.

Henri Bergson believed purpose was neither intrinsic nor extrinsic, but was malleable, unknowable, and perhaps non-existent in the sense that it could not be objectively defined. He believed intuition, based on experience and instinct, was equally if not more important than science and logic. He explained that creativity evolves in the same way as nature, through processes of fecundity, mutation and what he described as unforeseeable novelty. He felt there was a limit to reason and to what could be planned, and that randomness was vital in both the natural world and the creative work of artists. Vital to his philosophy was automatism; the idea that natural systems and creative individuals can act independently and unpredictably, without precedent or explanation.

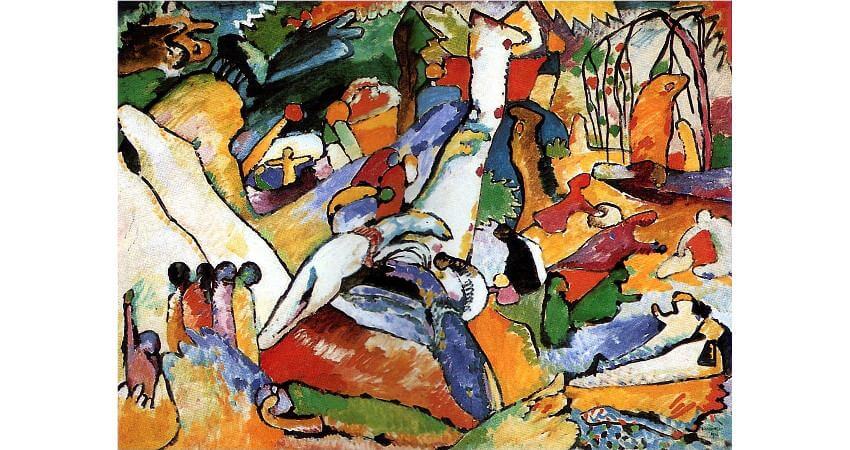

Wassily Kandinsky - Study for Composition II, 1910. 97.5 x 130.5 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, NY, US

Wassily Kandinsky - Study for Composition II, 1910. 97.5 x 130.5 cm. Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York City, NY, US

Biomorphic Art

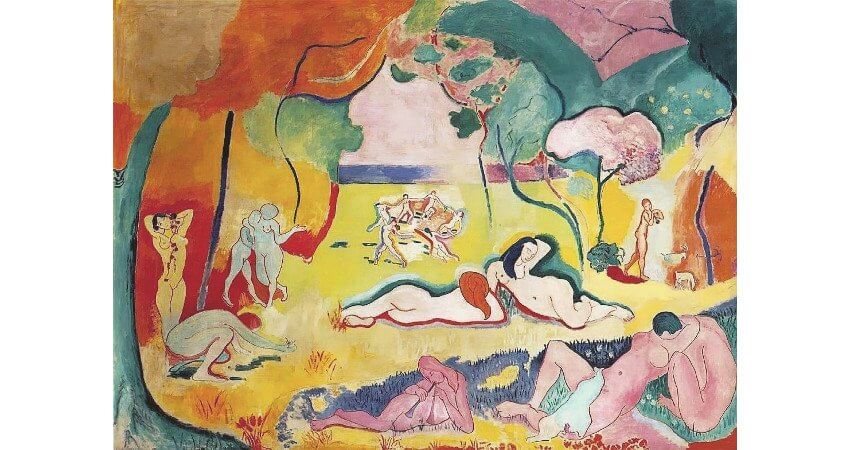

The ideas Bergson proposed were in stark contrast to the analytical way many artists were approaching their work. One of the earliest aesthetic manifestations of the natural processes Bergson described was the painting Le Bonheur de Vivre, by Henri Matisse. The painting is figurative but abstract. It shows people lounging nude in an Eden-like paradise. Biomorphic forms make up the natural surroundings, and the human forms, are corpulent and organic looking. The natural surroundings seem to be in a state of change, and the visual language they share with the human figures implies that humanity is also connected to the constantly evolving state of nature. The aesthetic of this painting formed the foundation of what would come to be considered biomorphic abstraction.

Biomorphic abstraction was an alternative for many painters to the intentional formalism that dominated the precise, geometric abstract tendencies of styles like Constructivism and Concrete Art. Wassily Kandinsky was particularly interested in the spiritual and musical aspects of abstract art. He combined biomorphic forms with the geometric lines and shapes in his earliest, purely abstract paintings. Although the painter Joan Miró insisted his paintings were not abstract, but representational of the dream images he saw in his head, he also famously incorporated biomorphic forms in his iconic, idiosyncratic style.

Henri Matisse - Le Bonheur de Vivre (The Joy of Life), 1905-1906. Oil on canvas. 175 x 241 cm. Barnes Foundation, Lower Merion, PA, US

Henri Matisse - Le Bonheur de Vivre (The Joy of Life), 1905-1906. Oil on canvas. 175 x 241 cm. Barnes Foundation, Lower Merion, PA, US

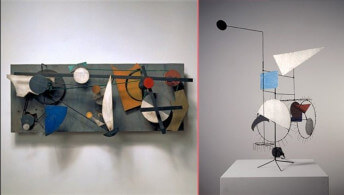

Biomorphic Sculpture

Shortly after its appearance in abstract paintings, biomorphism found its voice in the three-dimensional arts. The first biomorphic abstract sculptor was Jean Arp. He initially incorporated biomorphic shapes into his wall reliefs, which resembled egg-like objects with forms nesting within forms. He then expanded into making biomorphic sculptural objects in a huge range of shapes and size, gradually developing an immense language of organic, natural forms over the course of his career.

The language of bulbous forms that Arp created became a profound inspiration on the two Mid-Century British sculptors who truly defined the language of Modernist biomorphic abstract sculpture. The first was Henry Moore, who used biomorphism to express the essential connection between nature and humanity, and is best known for his monumental biomorphic abstractions of reclining human figures. The other was Barbara Hepworth, who utilized an enormous array of materials and techniques and vastly expanded the language of biomorphism in her monumental oeuvre.

Joan Miró - Painting, 1933. Oil on canvas. © 2008 Successio Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Joan Miró - Painting, 1933. Oil on canvas. © 2008 Successio Miró / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

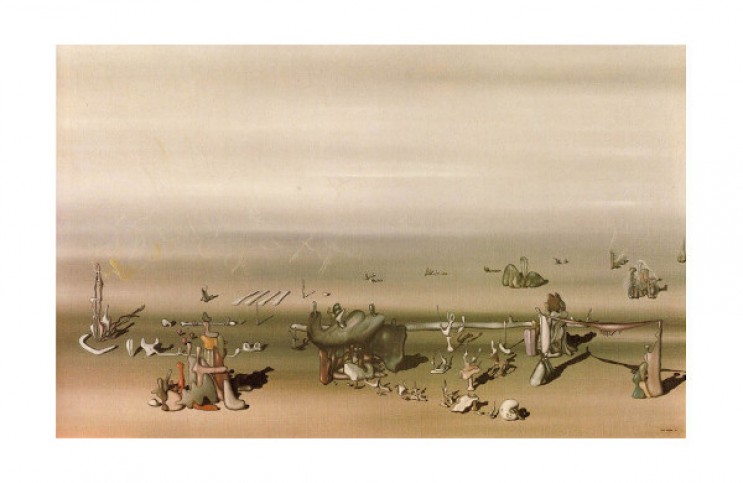

Surrealism and the Other Morph

One of the most influential styles on which biomorphism made its impact was Surrealism. Yves Tanguy painted uncanny, strangely lifelike, yet alienated forms in his desolate Surrealist landscapes. Their harsh light and unnatural surroundings evoke apocalyptic notions, and the forms themselves seem more like bones and remains than life itself. Meanwhile, the oozing, dripping, ever changing forms in the paintings of Salvador Dali inhabit a space somewhere between life and death. Even what seems to be made of stone threatens to come to life in his dreamlike images.

The Surrealist use of biomorphic forms adds an additional interpretive layer to the study of biomorphic abstract art. These painters had a special connection to the root word morphe. In Greek mythology, Hypnos is the god of sleep. His son is named Morpheus, and is the god of dreams. Surrealism was grounded in the study of the subconscious, and greatly influenced by the dream world. In that sense, it was the ultimate manifestation of biomorphism, as it relied on true automatism, the perfect expression of freedom and unforeseeable novelty, and it also inhabited the realm of Morpheus, the god of dreams.

The Contemporary Biomorphic Tradition

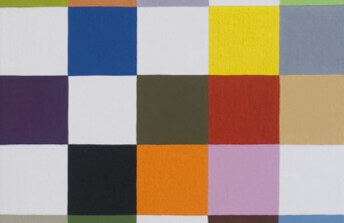

Today biomorphic forms have found a place within the general aesthetic lexicon of abstract art, and many contemporary artists incorporate the traditions of biomorphism in their work. The Los Angeles-based abstract painter Gary Paller explores those traditions directly by creating intuitive, layered compositions of organic forms that appear to be nesting together, engulfed in the rhythms of process and evolution. And the Boston-born New York artist Dana Gordon incorporates biomorphic patterns into his explorations of more formal abstract concerns, such as color, structure and line.

Though the root thinking behind biomorphism emerged as a reaction against rationality and science, the evolution of biomorphism in art has helped us realize that people no longer need to choose between reason and instinct. It has helped us marry the rational, analytical side of our nature to the uncanny, natural beauty of what Alfred H. Barr called the “mystical, the spontaneous and the irrational” biomorphic world.

Featured image: Yves Tanguy - I Await You, 1934. Oil on canvas. 28 1/2 x 45 in. (72.39 x 114.3 cm) Frame: 35 × 50 × 1 in. (88.9 × 127 × 2.54 cm). LACMA Collection

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio