Associative Abstraction of Howard Hodgkin - The Master of Color

Dec 13, 2016

Howard Hodgkin sees his paintings as offerings. He transforms the raw materials of memories and feelings into expressive objects that he hopes can be of use to others. It may sound heretical for an abstract painter to suggest art should be useful. Modernism is rife with so many artists who insist that art has no utilitarian purpose whatsoever. But Hodgkin believes that his paintings, which have been inspired by his own meaningful experiences, can in turn inspire meaning in the lives of others. As far as what exactly his paintings mean, Hodgkin is careful never to say. Aside from cryptic referenced found in their titles, he rarely even hints at the memory or feeling that inspired their creation. Rather than dictate what the viewer response should be, he leaves everything open, only evoking memories and moments through colors and brushstrokes in hopes that we, in an unmitigated way, will develop a relationship with him through his paint.

Associative Abstraction

Howard Hodgkin was born into an artistic family. His cousin was the British landscape painter Eliot Hodgkin, and was already on his way to success by the time Howard was born in 1932. But though Howard and Eliot are both now revered contributors to the history of British art, their approaches to painting are quite different. Eliot was strictly figurative in his approach, and once said his greatest achievement was to convince viewers to see the beauty in ordinary things, such as vegetables or common landscapes. Howard, however, adopted abstraction as a young man and believes that his paintings are not beautiful at all, and that to call them beautiful might even be to dismiss them.

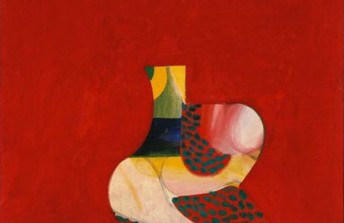

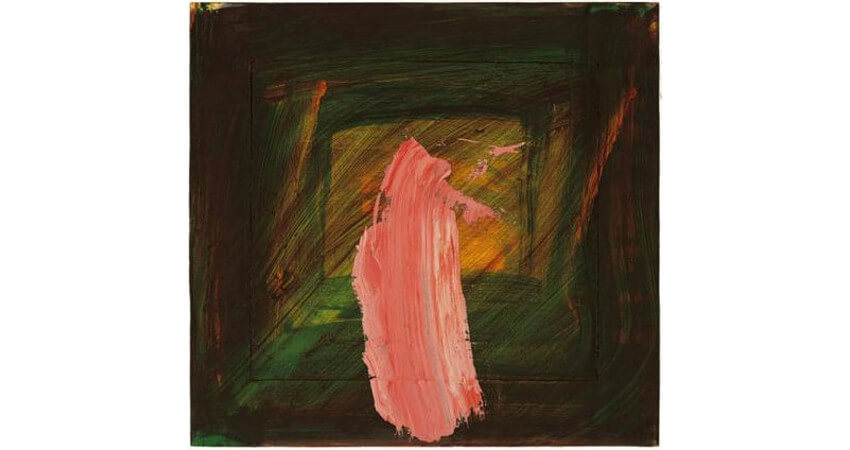

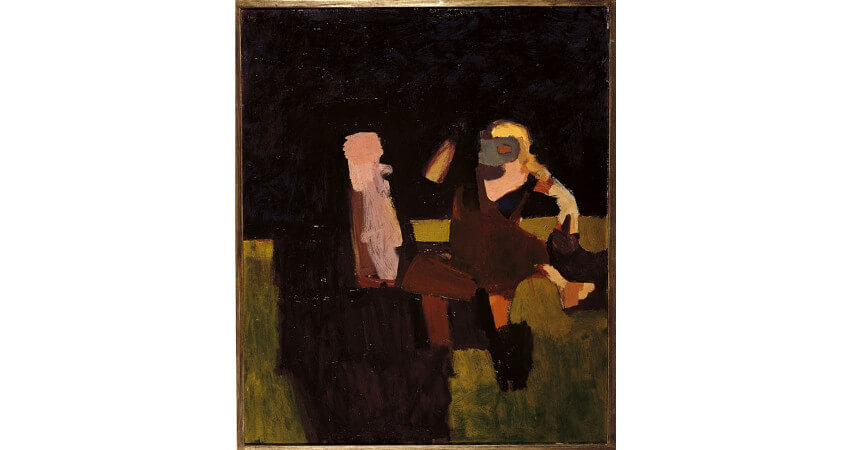

Howard Hodgkin - Art, 1999-2005. Oil on wood. 52.4 x 55.3 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Howard Hodgkin - Art, 1999-2005. Oil on wood. 52.4 x 55.3 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Howard relates to the paintings he makes as objects, but intends for them to be interpreted by viewers on an emotional level. Each painting he makes begins as he experiences impressions of a moment: the colors, the light, the surroundings and the forms. He then takes those impressions home and expresses them in his studio through paint. We call his process associative abstraction, since he creates non-objective imagery from personal associations. He calls himself a figurative painter of emotional situations.

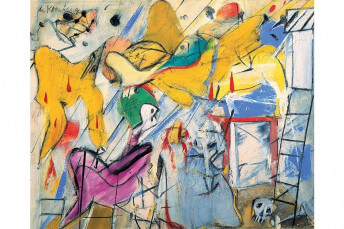

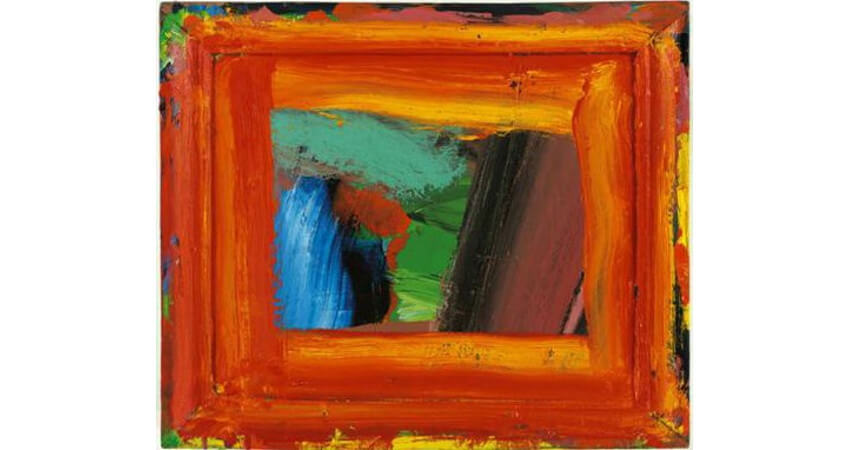

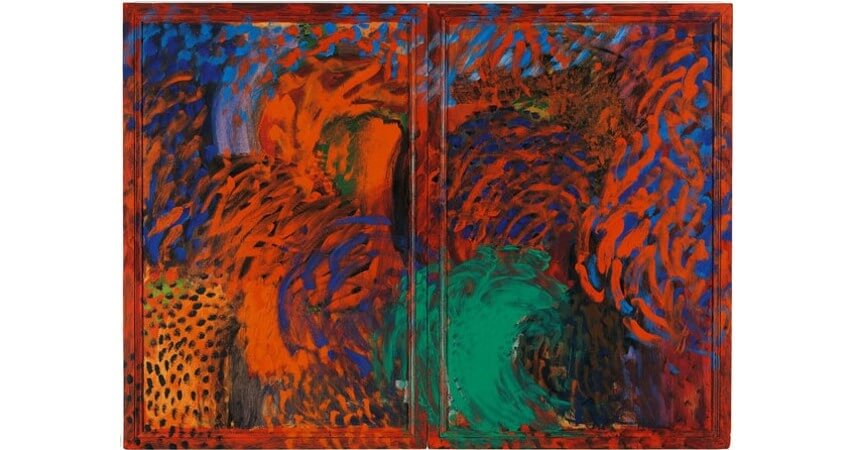

Howard Hodgkin - Learning about Russian Music, 1999. Oil on wood. 55.9 x 65.4 cm. Private Collection. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Howard Hodgkin - Learning about Russian Music, 1999. Oil on wood. 55.9 x 65.4 cm. Private Collection. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Finding Abstraction

The earliest works Hodgkin painted were figurative and representational. But in his late 20s he transformed his style to become more abstract. His forms became pared down, and he used color less to convey precise forms and more to express the overall emotional essence of the composition. He gave his abstract compositions non-specific, yet subtly communicative titles that hinted at private experiences and recollections.

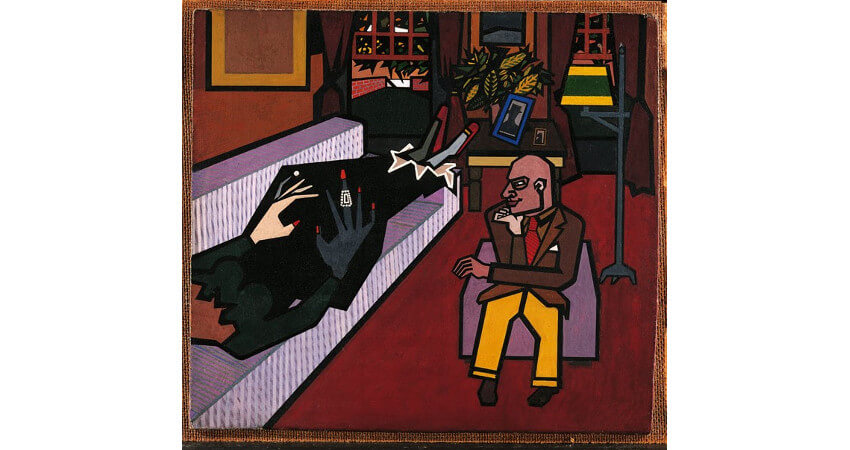

Howard Hodgkin - Memoirs, 1949. Gouache on board. 22 x 25 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Howard Hodgkin - Memoirs, 1949. Gouache on board. 22 x 25 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

As Hodgkin was embracing abstraction, his friend and contemporary David Hockney was becoming known as a figurative painter. Hockney garnered attention and financial success while Hodgkin remained relatively anonymous and struggled financially. Nonetheless, Hodgkin pursued his personal, intimate aesthetic style, searching for more nuanced ways of communicating his emotions through color and paint rather than strictly pursuing critical acclaim.

Howard Hodgkin - Gramophone, 1957. Oil on board. 76.2 x 63.5 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Howard Hodgkin - Gramophone, 1957. Oil on board. 76.2 x 63.5 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Controlled Objects

In the 1970s, Hodgkin developed a strategy for increasing his control over how viewers conceived of his paintings. He felt that the more he could get his paintings to stand out as objects, the more he could draw viewers in to consider them for a longer amount of time. Realizing that frames that were added to the images represented an intrusion into the image, he began either painting borders along the edges of his images or framing his paintings first and then painting the frames as part of the composition.

By painting the frame, he completely defied the painting as an object, and prevented it from being altered by additional aesthetic elements. He extended this act of control even onto the walls on which his paintings were hung, which he also considered to be a potential barrier between viewers and the work. At the Venice Biennale in 1984, Hodgkin painted the walls in his exhibition green. He noted in an interview at the time that white walls reflect too much light. The green walls did not reflect light, so all of the light could be reflected by his pictures.

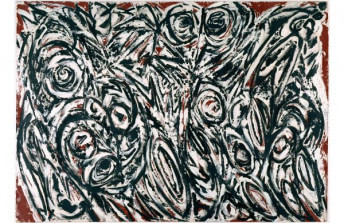

Howard Hodgkin - When Did We Go to Morocco, 1988 – 1993. Oil on wood. 196.9 x 269.2 cm

Howard Hodgkin - When Did We Go to Morocco, 1988 – 1993. Oil on wood. 196.9 x 269.2 cm

Maximum Expression

Hodgkin is still active as a painter today in his mid-80s. In a recent interview, he talked about the difficult time he had achieving recognition for his work. He mentions that although he found his mature style relatively young, it took decades more before anyone took him seriously. He even mentions contemplating suicide in his 30s. But he also found that as he aged he cared less and less about fame and recognition, and was able to focus more on developing strategies for the ever more direct expression of emotion.

His original transformation toward abstraction was about trying to show less and express more. By not painting things the way they look, he hoped to paint them the way they feel. He focused on the expressive potential of color, and the power of paint itself to communicate complexity. The more his work simply became about color and paint, the more the true subject matter—emotion—could show. Essentially, over time, he learned to let more be unsaid. Now in what he calls “old age,” he says he has finally allowed himself to let his paintings say as little as possible, so they can achieve maximum expression.

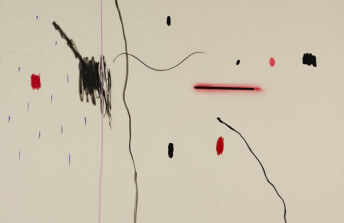

Howard Hodgkin - Night Thoughts, 2014 – 2015. Oil on wood. 37.1 x 47.9 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Howard Hodgkin - Night Thoughts, 2014 – 2015. Oil on wood. 37.1 x 47.9 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

Featured image: Howard Hodgkin - Tears for Nan (detail), 2014. Oil on wood. 28,6 x 29,8 cm. © 2019 Howard Hodgkin

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio