From Abstract to Figuration - The Path of Richard Diebenkorn

Jan 20, 2017

When Richard Diebenkorn died in 1993 he left behind a body of work that defended the importance of painting. Despite rubbing elbows with some of the most influential artists of his generation he remained staunchly individualistic, creating an oeuvre that stands today as unique and instantly recognizable. After beginning his career as an abstract painter in the 1940s, one that incidentally believed no worthwhile modern painter should bother with figurative work, Diebenkorn suddenly shifted his focus to portraiture, still life and landscape painting. The unexpected move had the odd effect of branding him as avant-garde, since it defied his convictions and those of almost every other painter of note. But then a decade later he transitioned back toward abstraction. In the midst of being told he was revolutionary, he said, “I'm really a traditional painter, not avant-garde at all”, adding that all he really wanted to do was “follow a tradition and extend it.” To his way of thinking the apparently different directions he took were part of a single path: a gradual evolution away from ideological confusion and toward an understanding of the ancient and everlasting problems involved in simply making good paintings.

A Traditional Rebel

Richard Diebenkorn is known today as a quintessential California painter. His loose-yet-balanced compositions and washed out color palette helped define the aesthetic of a culture of freedom, breeziness and amazing light. But Diebenkorn was born in Portland, Oregon. He moved to California at age two. Before becoming a professional painter, he served for two years as a US Marine during World War II. After the war he used his GI Bill privileges to attend art school. As did most artists of his generation, Diebenkorn threw himself wholeheartedly into Abstract Expressionism, the dominant art trend of the time. He made gestural compositions that conveyed the angst and energy of an artist obviously searching. And he was in good company, studying and teaching alongside other emerging California painters like Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still.

But Diebenkorn soon started moving around, studying and teaching in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and Urbana, Illinois, before moving back again to California. In his travels he became aware of a larger conversation occurring between painters of many different mindsets: one that had less to do with what he began to see as the false separation between abstraction and figuration, and more to do with the deeper relevance of what a painting can accomplish. He arrived at the conclusion that “all paintings start out of a mood, out of a relationship with things or people, out of a complete visual impression. To call this expression abstract seems to me often to confuse the issue.”

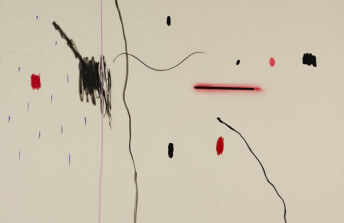

Richard Diebenkorn - Berkeley 3, 1953. Oil on canvas. 54 1/10 × 68 in. 137.5 × 172.7 cm. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

Richard Diebenkorn - Berkeley 3, 1953. Oil on canvas. 54 1/10 × 68 in. 137.5 × 172.7 cm. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

A World of Colors and Planes

The changing attitude Diebenkorn adopted toward abstraction put him in a strange position for a Modernist. Since the late 1900s, most abstract artists had originally trained as realistic figurative artists then transitioned into abstraction through a process of reduction toward a simpler visual language. Diebenkorn began with abstraction then transitioned into figuration. But now freed from the illusion of the philosophical differences between abstraction and figuration, he found that he was able to paint what he saw—human figures, faces, and urban and natural landscapes—while still exploring within these images the qualities and elements of abstraction he found most interesting.

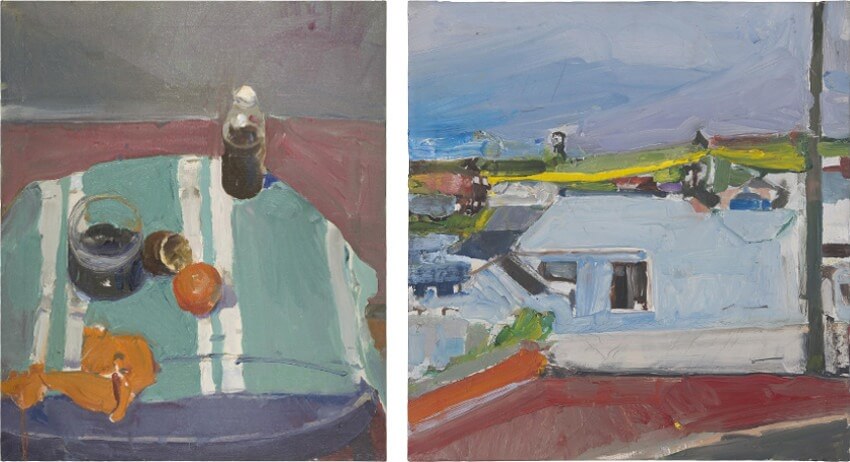

Richard Diebenkorn - Still Life with Orange Peel, 1955. Oil on canvas. 29 3/10 × 24 1/2 in. 74.3 × 62.2 cm (left) / Richard Diebenkorn - Chabot Valley, 1955. Oil on canvas. 49,5 x 47,6 cm (right). © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

Richard Diebenkorn - Still Life with Orange Peel, 1955. Oil on canvas. 29 3/10 × 24 1/2 in. 74.3 × 62.2 cm (left) / Richard Diebenkorn - Chabot Valley, 1955. Oil on canvas. 49,5 x 47,6 cm (right). © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

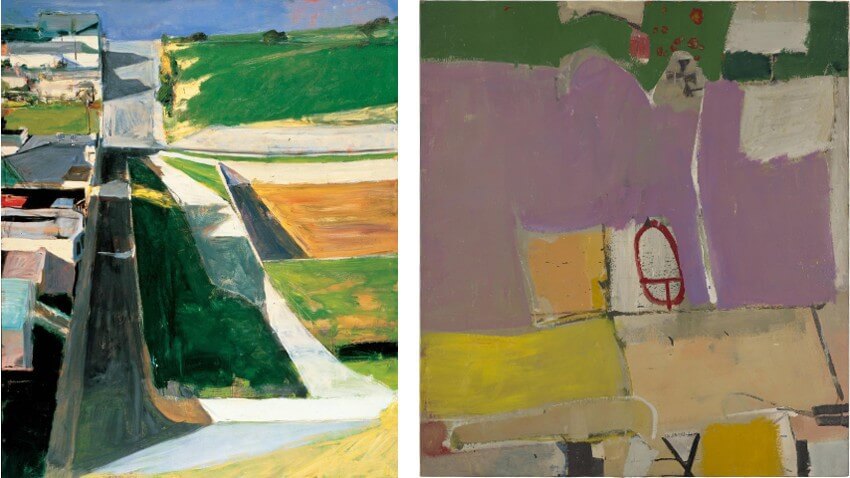

Rather than mimicking real life with hyper-realistic paintings, Diebenkorn translated the visible world into arrangements of color fields, lines, and quasi-geometric shapes. He worked with charcoal and oil paint, allowing multiple layers to show through to the final composition. Cityscape I is one of his most famous early figurative paintings. In it, geometric shapes, linear planes, abstract color fields, under layers, and the tortured marks of compositional perfectionism combine in a figurative vision that is simultaneously expressionistic, and somewhat abstract. Comparing it side-by-side to an earlier abstract work from his Albuquerque series, it is easy to see the hand of the artist is the same.

Richard Diebenkorn - Cityscape I, 1963. Oil on canvas. 60 1/4 in. x 50 1/2 in. 153.04 cm x 128.27 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Collection (left) / Richard Diebenkorn - Albuquerque 4, 1951. Oil on canvas. 50 7/10 × 45 7/10 in. 128.9 × 116.2 cm (right). © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

Richard Diebenkorn - Cityscape I, 1963. Oil on canvas. 60 1/4 in. x 50 1/2 in. 153.04 cm x 128.27 cm. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art Collection (left) / Richard Diebenkorn - Albuquerque 4, 1951. Oil on canvas. 50 7/10 × 45 7/10 in. 128.9 × 116.2 cm (right). © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

The Beauty of Paint

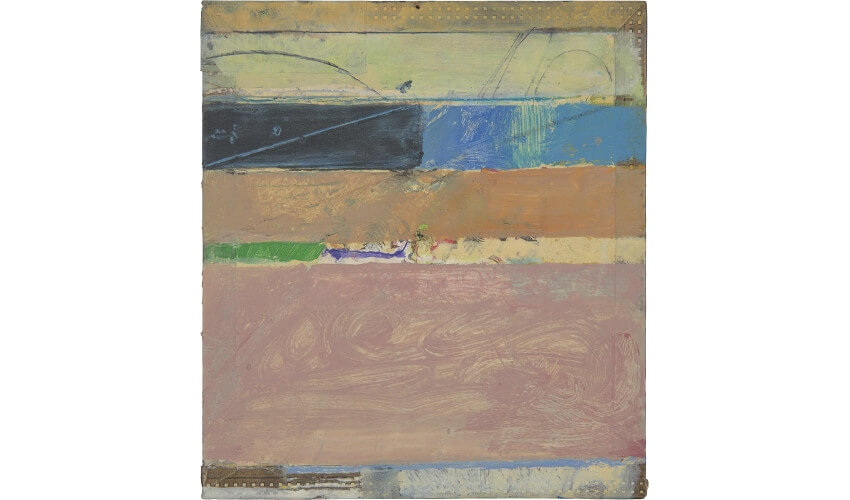

Around 1966, after a decade or so of figurative painting, Diebenkorn began a new series that to art historians heralded the return of the artist to pure abstraction. He named the series Ocean Park, after the beachfront Santa Monica neighborhood where his painting studio was located, north of Los Angeles. Indeed the Ocean Park paintings seem to lack any obvious reference to figurative elements. They appear geometric and abstract. But to simply call these paintings geometric abstraction, and label them as another departure from his previous work, is a simplistic reading.

In an interview Diebenkorn gave to CBS Sunday Morning in 1988, he mentions the impact his environment always had on his work. He elaborates that a sense of place more than anything else informed his mature paintings. The Ocean Park paintings are not a return to something anymore than the figurative paintings of the earlier decade were a departure from something. In both periods Diebenkorn explored the issues of composition, harmony, color and balance. The Ocean Park series does the same, using the light, shapes, and aesthetic arrangements of space Diebenkorn encountered in the real world, in this case the world of the Santa Monica beachfront, to inform a further investigation into the same issues.

Richard Diebenkorn - Ocean Park 43, 1971. Oil and charcoal on canvas. 93 × 81 in. 236.2 × 205.7 cm. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

Richard Diebenkorn - Ocean Park 43, 1971. Oil and charcoal on canvas. 93 × 81 in. 236.2 × 205.7 cm. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

How to Begin a Painting

Late in his career, it is unclear when, Diebenkorn wrote down a list of what he considered to be the accumulated lessons of his experience as a painter thus far. The list included ten original aphorisms. He called it “Notes to Myself on Beginning a Painting.“ The full list is available elsewhere online since he shared it often, so no need to include it here. But a glimpse at a few of the items on the list reveals much about his style, and about the mature attitude Diebenkorn developed toward abstraction, figuration and experimentation.

The first item on the list states: “Attempt what is not certain. Certainty may or may not come later. It may then be a valuable delusion.” Another item simply states, “Tolerate chaos.” These notes reveal an artist committed to searching. They show that he saw the objectivity of the so-called real world as only a starting point in an inward creative process. Whether painting a portrait, a figure or a geometric abstract composition he was working in a direction away from certainty, toward a universal sense of harmony. Another item on the list states, “Mistakes can’t be erased but they move you from your present position.” This sentiment manifests in the rich layers and textures of all of his paintings, through which his often difficult, time-consuming efforts assert their presence.

Richard Diebenkorn - Ocean Park 135, 1985. Oil, crayon, and ink on canvas. 16 3/4 x 17 1/2 in. 42.5 x 44.5 cm. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

Richard Diebenkorn - Ocean Park 135, 1985. Oil, crayon, and ink on canvas. 16 3/4 x 17 1/2 in. 42.5 x 44.5 cm. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

A Humble Giant

Richard Diebenkorn attained many highpoints over the course of his career. He was a founding member of the Bay Area Figurative School in the 1950s, which is credited with reintroducing figurative painting to modern American art after Abstract Expressionism. By the mid-1980s he had become one of the highest paid living artists in the United States. And in the 1990s, he even received the National Medal of Arts, one of the highest honors the US Government bestows upon an artist.

But despite his impact, or perhaps in an attempt to defend himself from it, he remained a humble and hard working artist. He eventually left the city, moving back north to the Russian River Valley west of Napa. There, he continued painting until sickness debilitated him. As long as he could work, whether painting abstractions, as in his late Cigar Box Lid series, or painting landscapes of his wilderness home, he remained true to his lifelong passions: an investigation of color, space and harmony, and a dedication to the ancient challenges and traditions of painting.

Richard Diebenkorn - Cigar Box Lid 8, 1979. Oil and graphite on wooden cigar box lid. 6 1/2 x 5 3/4 in. 16.5 x 14.6 cm. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

Featured image: Richard Diebenkorn - Ocean Park 89.5 (detail), 1975. Oil and charcoal on canvas. © The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation, Berkeley

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio