The Mesmerizing Animations of Oskar Fischinger

Jul 22, 2017

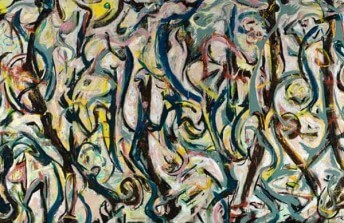

This year is the 50th anniversary of the death of Oskar Fischinger, a prescient genius who came closer than any other artist has to expressing the mystifying, abstract commonalities that exist between music and images. Through his animated films, Fischinger correlated the visual languages of shapes, forms, lines and colors with the musical language of notes, beats, harmonies and dissonances. Through his invention of the Lumigraph, a light-emitting device manipulated by hand similarly to a musical instrument, he demonstrated the potential for aesthetic-emotional bonds to be created by improvised, dynamic color compositions played on a machine. And through his paintings he conveyed the heightened conceptual planes hidden in his motion pictures by freezing them on simplified, two-dimensional surfaces. Meanwhile, throughout his career, in writings and speeches, he thoroughly laid out his artistic intentions. “I want this work to fulfill the spiritual and emotional needs of our era,” he wrote in 1950. “For there is something we all seek—something we try for during a lifetime...hoping...one day, perchance, something will be revealed, arising from the unknown, something that will reveal the True Creation: the Creative Truth!”

Oskar Fischinger: A Born Artist

Some artists are made; others are born. Oskar Fischinger never studied art in school. Born in 1900 in Hesse, Germany, he was, like most members of his generation, drafted into military service as a teenager. But due to his poor physical condition he was not forced to fight for Germany in the war. Instead, he took a job in an organ factory. That early exposure to the mechanisms of musical creation would prove fateful for Fischinger later on, especially when added to the engineering education he was able to receive after the war, when his family moved to Frankfurt. Perhaps these experiences were not typical of someone destined to become a great artist, but they were creative in their essence, and as it turns out they were perfect for the destiny that awaited this particular artist.

In 1921, Fischinger made the acquaintance of avant-garde German film director Walter Ruttman. Ruttman was one of a handful of artists experimenting with film as an abstract medium, exploring the ways it might interact with other art forms. Fischinger was inspired by the work Ruttman was doing, and thanks to his mechanical and engineering backgrounds he managed to find a way to impress Ruttman in return. He did so through the invention of a mechanical animation device: a “wax slicing machine.” After hearing about the device, Ruttman was so impressed he asked Fischinger for the rights to use it. Fischinger licensed the rights to his machine to Ruttman, and also subsequently moved to Munich, where he gained access to more equipment, which enabled him to experiment further on his own.

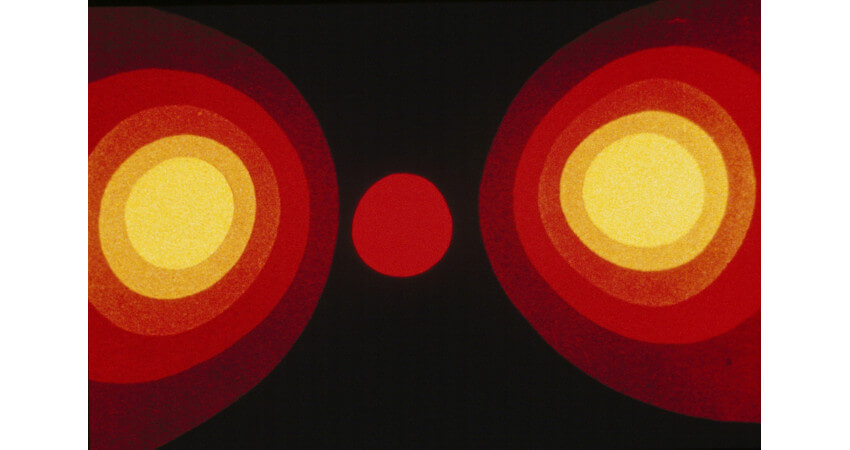

Oskar Fischinger - still from Radio Dynamics, 1942, © Center for Visual Music

Oskar Fischinger - still from Radio Dynamics, 1942, © Center for Visual Music

The Films

While in Munich, Fischinger made some of his earliest films.Rather than mimicking the realistic world, they studied the other ways light and soundcould interact in a motion picture. In 1926, he wrote one of his seminal essays, titled Eine neue Kunst: Raumlichtmusik, or A New Art: Spatial Light Music. Though it appears not to have ever been published in his lifetime, it is now on file at The Center for Visual Music in Los Angeles, which owns and manages the Fischinger oeuvre, including his films and papers. The thoughts Fischninger expressed in this essay, along with the achievements evident in his early films, put Fischinger in the philosophical company of artists such as Wassily Kandinsky, who believed strongly in the ability of non-objective imagery to communicate spiritually on the same abstract level as music. But by focusing on films rather than painting, Fischinger was able to understand an essential difference between music and images: that music, unlike static imagery, occurs in time.

A single note lasting only a moment does not have the same emotional effect on a listener as a symphony played over the course of an hour. And the same is true for images. A single visual composition on a painting does not have the same emotional effect on a viewer as a visual composition that plays out over the course of time in a moving picture. By applying that basic thought process, Fischinger spent the next two decades creating some of the most groundbreaking abstract, animated films ever made. Some were set to music, and have been called the first music videos. But they were nothing like music videos as we know them today. They were set to music only in an attempt to examine the similarities in the ways visual compositions and musical compositions communicate abstractly to our brains.

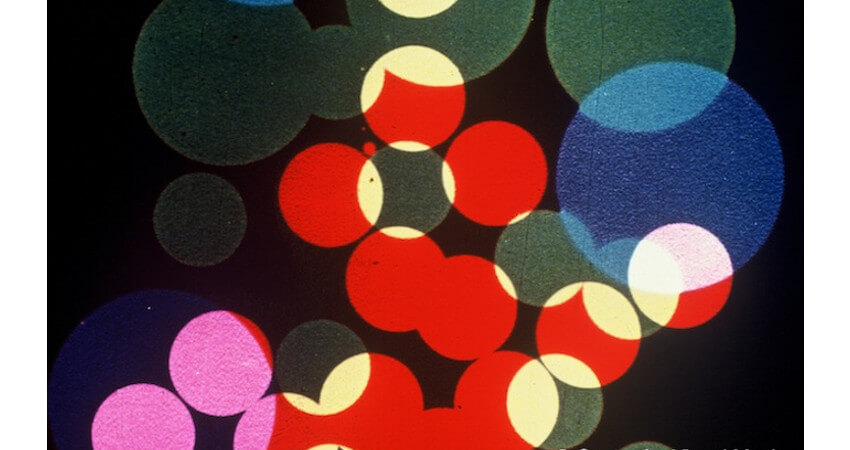

Oskar Fischinger - still from Kreise, 1933-34, © Center for Visual Music

Oskar Fischinger - still from Kreise, 1933-34, © Center for Visual Music

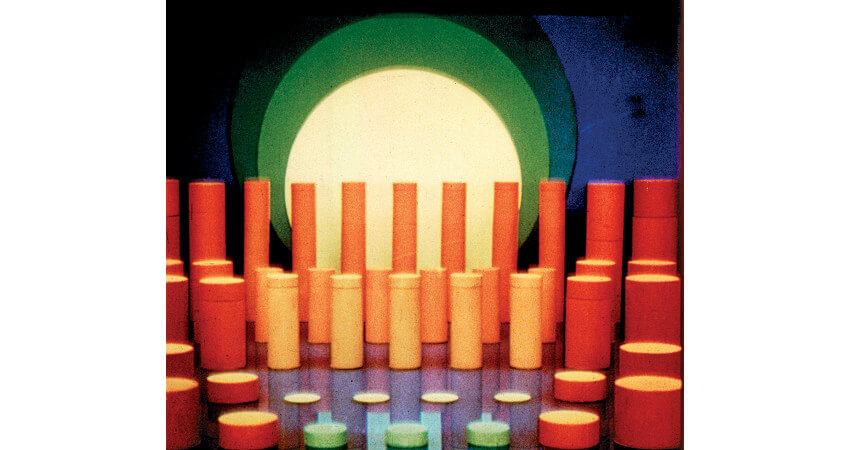

Composition in Blue

In 1935, while living in Berlin, Oskar Fischinger accomplished what many people consider to be his magnum opus: a film titled Composition in Blue. Shot on 35 mm color film, the animated short is set to a tune from The Merry Wives of Windsor, an opera by the German composer Otto Nicolai, based on the play by the same name by William Shakespeare. Throughout the film, vividly colored, abstract forms dance in perfect sync with the music. The background seems to shift from two to three dimensions, and frequently collapses into itself, transforming in an endless, whimsical, visual delight.

One remarkable aspect of Composition in Blue is how it was made. Fischinger hand-built each of those little forms dancing around in the film. Those are painted models, meticulously moved as the film was shot, one frame at a time. Each frozen frame could, under different circumstances, constitute an abstract painting. Or, had he wished, each composition prior to being filmed could have been considered as a sculptural installation. But it was only in motion, playing out over the course of time, that Fischinger believed these abstract images could attain the same impact as musical compositions, so it was toward that end that he directed the work.

Oskar Fischinger - still from Composition in Blue, 1935, © Center for Visual Music

Oskar Fischinger - still from Composition in Blue, 1935, © Center for Visual Music

The Paintings

Composition in Blue achieved international recognition. Due in part to its success, Fischinger was able to come to America in 1936, where he took various positions in Hollywood working for Paramount, Walt Disney, and other studios. But he quickly learned about the chasm that exists between the idealistic goals of artists and those of commercial film production companies. Unable to find the financial support to continue making his purely artful animation work, eventually Fischinger was forced to abandon film. He instead focused much of his attention in the late 1940s on his invention, the Lumigraph. And then ironically, he spent the last 15 years of his life as a painter.

The paintings Fischinger created are remarkable in their variety. Like his earlier animations, they seem to contain the abstract visual language of every other abstract artist of the 20th Century. But these are not derivative works. On the contrary, most of these images were initiated by Fischinger long before artists like Josef Albers, Bridget Riley, Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland arrived at them on their own. And contrary to expectations, rather than taking anything away from his films, his paintings add power to his ideas about music and images and the effects of experiencing them in time. Each painting is a captured moment—an isolated fragment of a larger experience. Seeing them in his movies takes us on a journey. Seeing them in his paintings lets us appreciate them like connoisseurs.

Oskar Fischinger - still from Motion Painting no I, 1947, © Center for Visual Music

Oskar Fischinger - still from Motion Painting no I, 1947, © Center for Visual Music

Worst Homage Ever

Oskar Fischinger was obviously a pioneer, so it is no surprise people often want to pay homage to him and his accomplishments. But last June, on what would have been his 117th birthday, Google “paid homage” to Fischinger with a Google Doodle—one of those interactive distractions Google offers users on its search page. The doodle gave visitors a chance to alter a musical-visual composition by clicking on the screen. Though amusing, it was an absurd homage to Fischinger. Said Fischinger once in reference to his experiences in Hollywood: “No sensible creative artist could create a sensible work of art if a staff of co-workers of all kinds each has his or her say in the final creation...They change the ideas, kill the ideas before they are born, prevent ideas from being born, and substitute for the absolute creative motives only cheap ideas to fit the lowest common denominator.”

How Google thought a highly paid programmer working for a commercial factory could pay homage to this artist by offering literally everyone with an Internet connection a “say in the final creation” is unknown. Somewhere, something is getting lost in translation. But will the rest of humanity ever catch up to Oskar Fischinger? Perhaps. It is not difficult to understand what Fischinger intended for us to do with his work. He intended for us to use it for spiritual and emotional sustenance. Maybe the best ways for us to pay homage to his legacy is not by creating silly parlor games, or by reducing his accomplishments to statements like, “Wow, he did all that without a computer?!” Instead maybe we should give him his due as an artist, a philosopher and a poet and try to understand the deeper purpose to his work, which calls us to reconnect with the hidden mysteries that bind our varied, and still quite misunderstood, sensory powers.

Google celebrating 117th birthday of Oskar Fischinger, © Google

Google celebrating 117th birthday of Oskar Fischinger, © Google

Featured image: Oskar Fischinger - still from Allegretto, 1936-43, © Center for Visual Music

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio