Anni Albers and the Abstraction in Textile Art

Sep 27, 2016

When the Bauhaus was established in Germany in 1919, it was a relatively forward-thinking academy. It synthesized the study of art and design in pursuit of a total approach to both, and it opened its enrollment to all genders. Yet when Anni Albers enrolled as a student there in 1922, the Bauhaus still restricted female artists to taking classes only in textiles. Albers was a skilled painter when she applied. Nonetheless, undaunted, she embraced the textile curriculum and found it both challenging and enlightening. In fact, she was so inspired by the textile medium that she devoted the rest of her life to mastering its unique properties. By the time she passed away in 1994, Albers had become one of the most respected textile experts in the world, and one of the most influential abstract artists of her generation. Through her abstract textiles she achieved the epitome of Bauhaus ideals: she fused art, craft and design in service to the architectonic spirit.

A Structure Looking For a Function

Textiles and architecture have much in common. Clothing and shelter are two of the most primitive and fundamental needs of humanity. The first architectural structures built by humans, stone monuments used as calendars, date back 100,000 years. And evidence exists that our ancient ancestors were wearing clothes at least 500,000 years ago. But the word textile does not refer to such clothes as animal hides. Rather, a textile is a fabric made by interlacing fibers into cloth. The earliest evidence of woven fibers dates back about 34,000 years. For perspective, the oldest hand-axes date back 2.6 million years, and the oldest evidence of controlled use of fire by humans dates back 1.7 million years.

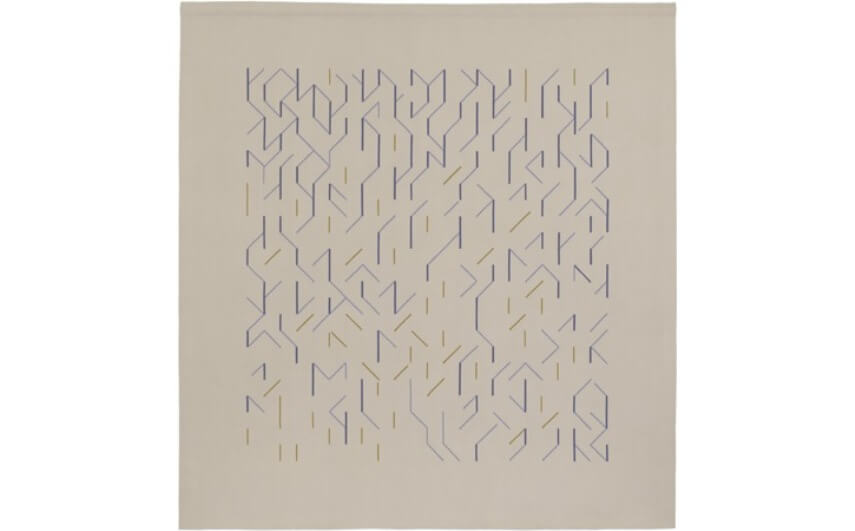

But the craft of weaving may be older than textiles themselves. The earliest woven baskets date back about 50,000 years. One of the techniques used in basket weaving is called the twill weave. Carved stones found in Africa called the Blombos Cave Shells, which date back at least 70,000, show images of a twill weave. Since carbon dating can only tell us when these rocks were buried, not when they were carved, it is impossible to know exactly how old they are. But their very existence is fascinating. They indicate that either weaving is far more ancient than we think, or the patterns involved in the technique existed as abstract structures in the aesthetic lexicon of humans before they found a practical use in the creation of functional forms.

70,000-year old twill weave pattern carved on a pre-historic African stone

The Art of Pre-Industrial Craft

By the time Anni Albers enrolled in the Bauhaus and started learning how to create textiles, the practical necessity for hand weaving was long gone. The process of making textiles had become fully industrialized. High capacity, mechanical looms had already existed for more than a century. Nonetheless, the technical aspects of weaving had hardly changed at all from their prehistoric roots. Even today there remain only three basic types of weaves: plain, twill and satin, all of which date back to antiquity.

Despite its antiquated nature, pre-industrial weaving was exactly what Anni Albers learned at the Bauhaus. She studied traditional tools, such as the backstrap loom, traditional materials, such as flax and hemp, and mastered the underlying structures of the basic weaves. And Albers also learned to experiment, which she believed was the most part of her education. As she wrote in her 1941 essay Handweaving Today: Textile Work at Black Mountain College, “If handweaving is to regain actual influence on contemporary life, approved repetition has to be replaced with the adventure of new exploring.” At the Bauhaus she tested out new materials, such as animal hair and metallic thread, and experimented with new patterns that allowed her to weave elaborate and modern abstract images into her textiles.

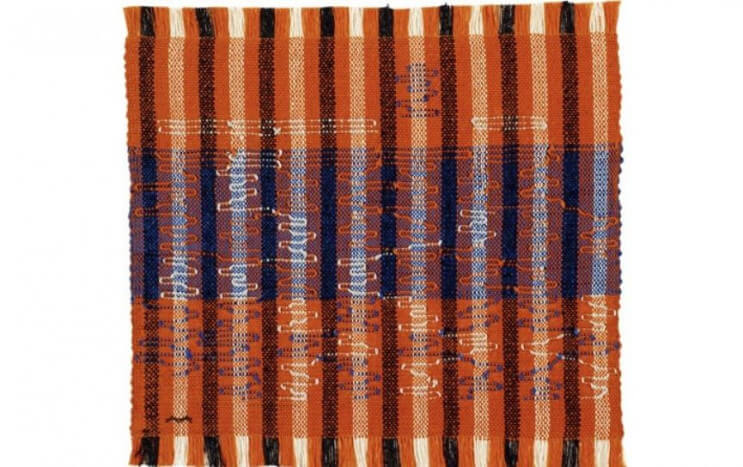

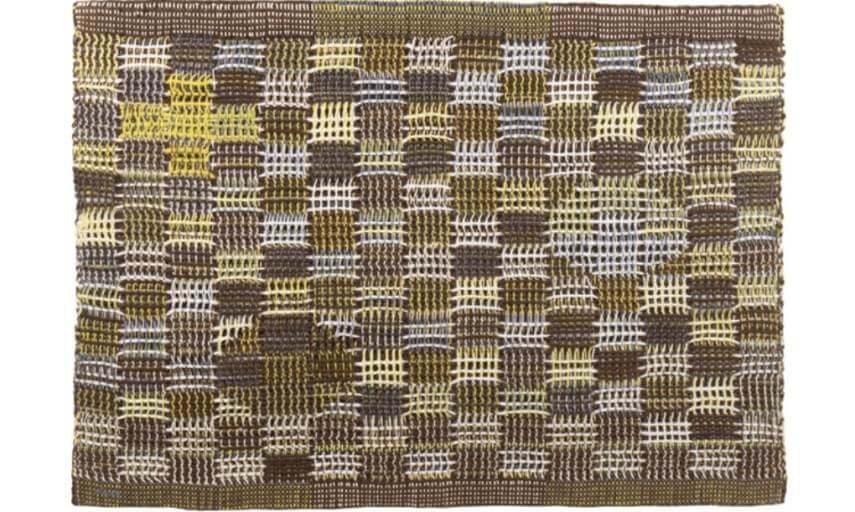

Anni Albers - Wallhanging, 1984. Wool. 98 × 89 in. 243.8 × 226 cm. © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

Abstract Qualities in Anni Albers Textiles

One definition of abstraction is something that deals with the realm of ideas rather than the objective realm. In that sense, Albers learned at the Bauhaus that the process of making art is in itself an abstract experience. By structuring their curriculum as a search for a total approach to art and design, the academy put ideas at the forefront of their education. But another definition of abstraction has to do with content. It was in that sense that abstraction has always been controversial in art, as viewers debate over the meaning of what they see. It was also in that sense that, because of the unique relationship viewers had with textiles, Albers was allowed more freedom to explore abstraction than was granted many of her contemporaries who worked in other mediums.

The reason for popular acceptance of abstract images on textiles may have something to do with the ancient traditions of the medium. For the most part, people consider textiles to be functional items. It matters little what patterns exist on a blanket when you just need it to keep you warm. An abstract geometric painting may evoke outrage for being incomprehensible, but an abstract geometric textile is unlikely to be considered controversial. In fact, it is likely to be considered aesthetically beautiful. Abstract geometric patterns have existed on textiles for tens of thousands of years. Perhaps, though we may have previously looked at them as mere decoration, those ancient abstract textiles, like those Albers made, had a different meaning or function than we know.

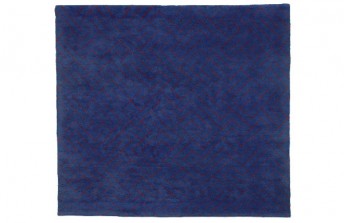

Anni Albers - In Orbit, 1957. Wool. 21 ½ x 29 ½ in, 54.6 × 74.9 cm. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art. © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

On Weaving

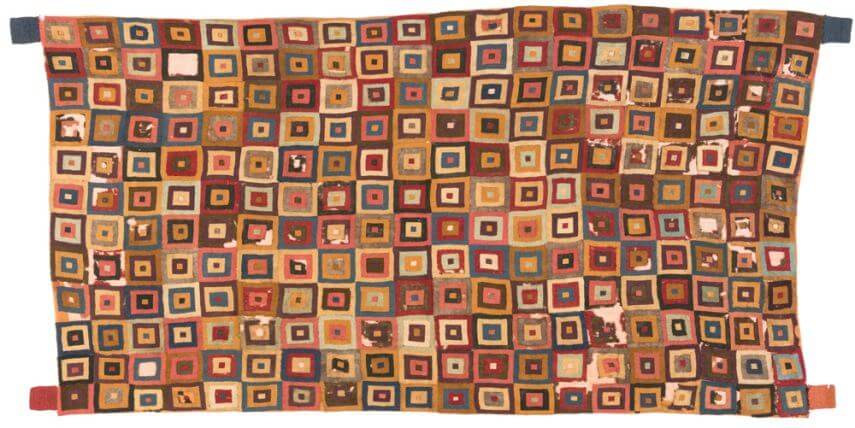

After the Bauhaus closed down in 1933, Albers moved to the United States and taught at the Black Mountain College. Throughout her career she continued teaching, and also wrote extensively about art. She lectured about textiles and advocated for the importance of art education. She also travelled extensively to Central and South America, where she became enthralled with the rich history of textile art of the local ancient indigenous cultures. In 1965, Albers dedicated On Weaving, her seminal book, to “my great teachers, the weavers of ancient Peru.”

Rather than dedicating her book to her Bauhaus teachers or her colleagues at the Black Mountain College she chose to dedicate it to her ancient predecessors. What was it that she learned from them, and how did she learn it? The answer may be found in the demands of having to give up painting and drawing in order to learn a completely new medium. As she wrote in her 1944 essay One Aspect of Art Work, “Our world goes to pieces; we have to rebuild our world. Out of the chaos of collapse we can save the lasting: we still have our ‘right’ or ‘wrong,’ the absolute of our inner voice—we still know beauty, freedom, happiness…unexplained and unquestioned.” The process of relearning how to be an artist allowed her to deconstruct for herself what art is. She already understood the creative impulse and the feeling of completing an artwork. Now could connect with the original, primeval evolution of art, going slowly and intentionally from impulse to action to finished object, same as the ancient weavers had done.

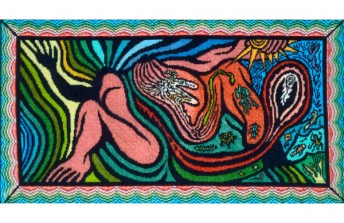

Ancient Peruvian abstract textile

A Special Faculty of the Mind

The wall hangings and textiles Albers created are stunning in terms of their complexity. Their value as abstract artworks rivals that of the work of any of her contemporaries. But even more valuable are the insights Albers gained into the deeper abstract nature of the artistic process, and the ways that process relates to everyday life. She wrote extensively about her thoughts on that subject, and in her writing encouraged us to look at the underlying value of art. She wrote about how it teaches us how to be patient, to trust our instincts, to overcome challenges and to see a project through to the end.

Albers believed that each step in the process of making art reveals its own mysteries about the workings of the mind. Like a textile, the art making process is a structure intertwined with opportunities to analyze our own motivations, and to question the larger meaning of our actions. As Albers expressed it, “Art work deals with the problem of a piece of art, but more, it teaches the process of all creating, the shaping out of the shapeless. We learn from it that no picture exists before it is done, no form before it is shaped.” Through her work she not only conveyed abstract content, she communicated the idea that like science and faith, the quest to make art is a fundamental drive of human consciousness. It is a path not only toward knowledge of the universe, but also toward knowledge of the self.

Featured Image: Anni Albers - Intersecting, 1962. Cotton and rayon. 15.75 × 16.5 in. 40 × 41.9 cm. Private Collection. © 2018 The Josef and Anni Albers Foundation

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio