How an Abstract Digital Drawing by Claire Malrieux Responds to Weather

Dec 6, 2017

Claire Malrieux has a knack for devising artworks that elucidate the concept of abstraction in fascinating ways. Her most recent work, Climat General, premiered at the 2017 Venice Biennale in the Hyperpavilion, a space dedicated to post-digital art. The work was simultaneously on view in the Gothic sacristy of the Collège des Bernardins in Paris. It consists of an animated, digital drawing projected onto a screen. The image evolves in real time according to the direction of a computer program. That means each time you look at the drawing it will be different. And since there is no predetermined aesthetic end point toward which the work is moving, every moment is as demonstrative of the concept as every other moment. Malrieux calls the work a picture of the Anthropocene (an era in the history of Earth defined by the moment when the impact of humans on the ecosystem became measurable). To create Climat General, she began by digitally drawing a series of forms, shapes, and linear patterns which she felt were representative of Gaia, the mythological Greek personification of Earth. She then associated each of those drawn elements with data points correlating to global meteorological data. The computer program monitors incoming weather data and instigates visual output, which translates into the slowly evolving, animated drawing that unfolds on the screen. Viewers can sit and watch as long as they want. A minimalist, droning soundtrack and low ambient lights create an environment conducive to lengthy viewings. The question then becomes, what are the viewers seeing? Is this art or science? Is it beautiful or horrible? And is it concrete or abstract?

Generative Art

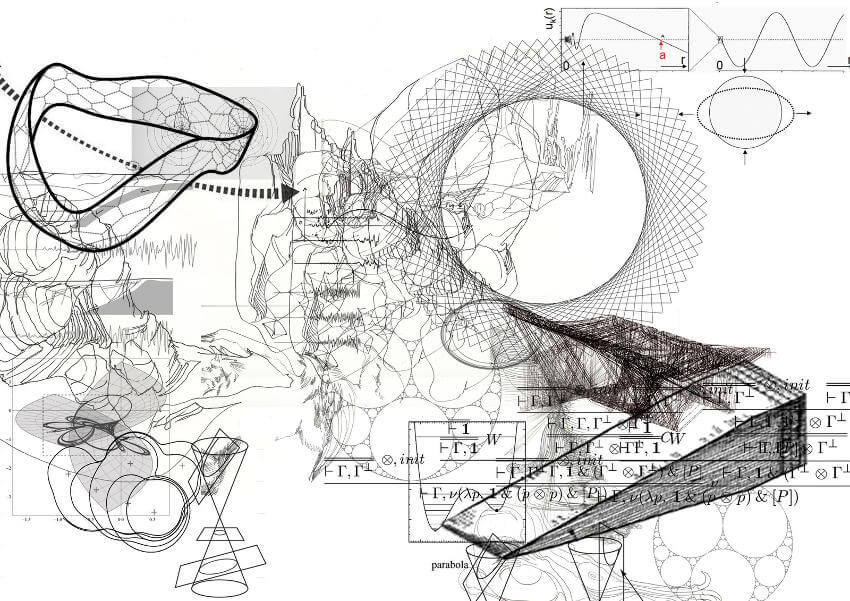

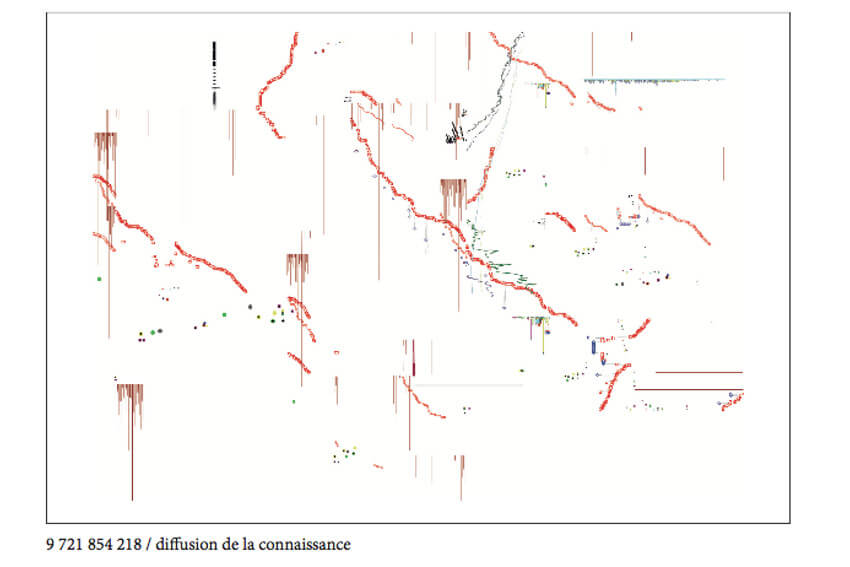

A graduate of the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, Malrieux has been working in the realm of computer generative conceptual art for several years. In 2014, she initiated a project called the Atlas of the Present Time, which is still ongoing. Like Climat General, Atlas of the Present Time uses a computer program to create drawings based on incoming data. In this case, her collaborators are scientists around the world. Says Malrieux, “[The project] builds itself through the daily generation of a canvas showing a collection of written notes, diagrams and sketches collected from the scientific community.” The work is partly a collection of drawings made by other people, partly a kinetic documentation of spontaneous academic thoughts, and partly an aesthetic news feed showing current advancements in science, no matter their interconnectivity or meaning.

Claire Malrieux - Atlas du Temps Preset, Composition 6 12 2017, © Claire Malrieux

Claire Malrieux - Atlas du Temps Preset, Composition 6 12 2017, © Claire Malrieux

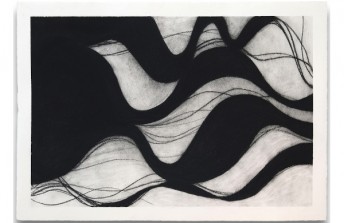

In 2015, Malrieux expanded on her idea with a series of five drawings titled The Vibratory Economy. For this series, she connected various graphic elements associated with high frequency stock trading with the mathematical theories of fringe Russian scientist Grigory Grabovoy. Grabovoy is the author of a book called The Practice of Control, The Way to Salvation, which alleges people can live forever and even return from the dead. He is currently imprisoned in Russia for fraud after taking payments from families in return for falsely promising he could resurrect their murdered children. His scientific equations relate to an idiosyncratic brand of quasi-spiritual geometry. By combining them with stock market data, Malrieux created pictures of moments in human culture that combine extremes of thought and theory, commenting broadly on the human connection between money and belief.

Claire Malrieux - Generative Drawing , 2015, © Claire Malrieux

, 2015, © Claire Malrieux

The General Climate

With the realization of Climat General, Malrieux takes her concept to a new level. She combines the ontological rigor of Atlas of the Present Time with the atmosphere of speculation and fear that surrounds The Vibratory Economy. We are watching real scientific data that would, were we able to translate it, show us concrete reports about what is happening around the world at this moment. If we were to watch the drawing unfold over a long enough period of time, we would see meteorological patterns emerge. We might be able to see climate change represented on the screen. We might even be able to isolate localized variations in weather that we could perhaps tie in with the particular habits of the humans who live in that area. Except there is one problem stopping us from doing that: we do not understand the drawings we are watching. We do not know what each form, shape, line or pattern correlates to in terms of weather data. So the experience we are having is not concrete. Although we know the pictures relate to weather, we cannot reach any conclusions about what they mean.

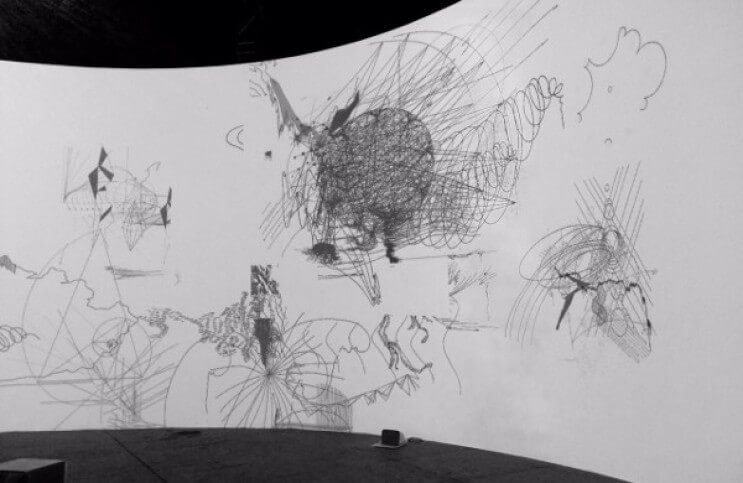

Claire Malrieux - Climat General, 2017, Computer generative graphics, © Claire Malrieux

Claire Malrieux - Climat General, 2017, Computer generative graphics, © Claire Malrieux

What we are left with is the abstract experience offered by Climat General. We can interact with the evolving pictures on our own terms. We can assign meaning to the images beyond the parameters set up by the artist. Or we can just sit back and enjoy the show if we want. Such a thought—contemporary art viewers smiling pleasantly as a kinetic drawing shows them the slow catastrophe of climate change—might conjure images of the Roman emperor Nero, playing his fiddle while he watches Rome burn. But the success of this work lies in the fact that Malrieux is not overtly making that statement. The climate is always; that is all this picture shows us. We cannot say how that will affect humanity or the other creatures on this planet. We cannot predict what will happen in the future with the weather any more than we can predict what will happen in the future with the drawing. Nor can we predict what it will mean, not only for us later in life but for those who come after us. Maybe our descendants will see us as Neros, and artists like Malrieux as our fiddles. Or maybe Malrieux is showing us something hopeful by demonstrating to us that we can never fully predict the long term effects of the systems we create.

Featured image: Claire Malrieux - Climat General, 2017, © Claire Malrieux

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio