Elles Font l’Abstraction - An Interview with Pompidou Chief Curator Christine Macel

Apr 28, 2021

Centre Pompidou will write history this summer with Elles font l’abstraction - the most comprehensive elucidation ever of the contribution of female artists to the development of abstract art. Pompidou Chief Curator Christine Macel assembled more than 500 works by 106 artists for the exhibition. Far from simply filling galleries with art, Macel took this opportunity to demonstrate what the role of a curator truly is-curators write, and at their best correct, art history. Dozens of the artists she selected will be familiar to audiences. Scores of others will be completely new, even to experts in the field. That is because Macel and her team have done the incredibly hard work of discovering and spotlighting global female voices who, despite their genius and influence, were omitted from the art historical canon. Spanning from 1860 through the 1980s, the exhibition and supporting documentation-including writing, films and lectures-will forever change our understanding of the evolution of abstraction as a plastic language. After my recent interview with Macel, I have come to believe it is only the beginning. Our conversation follows below.

Thank you for speaking with us, Christine, I have been a fan of your work since you curated the Venice Biennale in 2017. Is Elles font l’abstraction the most ambitious institutional attempt that you know of to appropriately recognize the international contribution of female abstract artists?

Yes, indeed. That is why I decided to make this research and exhibition. There was clearly a process of invisibilisation of women artists in the historiography of abstraction.

What was the most challenging part of bringing this exhibition to Centre Pompidou?

The loan process and the budget issues, as well as the pandemic situation. But I must say that there was an incredible support from the museums and private collectors all over the world, as well as sponsors. In the middle of the pandemic, I could count on the support of Van Cleef and Arpels, Luma Foundation, the Friends of the Pompidou, etc., that were decisive to realize this project. Not to mention the collaboration with the Guggenheim Bilbao that was crucial for this exhibition. A lot of art historians and scholars have been also very supportive. First of all Griselda Pollock, who is one of the many writers of the catalogue and our guest of honor for the symposium with Aware association. Artists themselves were also so enthusiastic. It was a big boost of energy! I had great discussions with Sheila Hicks, Dorothea Rockburne, Tania Mouraud, and Jessica Stockholder, to only name a few.

Those four artists in particular have such different visual languages. It is refreshing to see the incredibly broad range of visual positions represented in this show.

My statement is to open the definition of mediums concerned by abstraction, following the positions of the artists themselves. Spiritualism, dance, decorative arts, photography, and film have been part of this historiography. I want also to insist on each artist as particular and original.

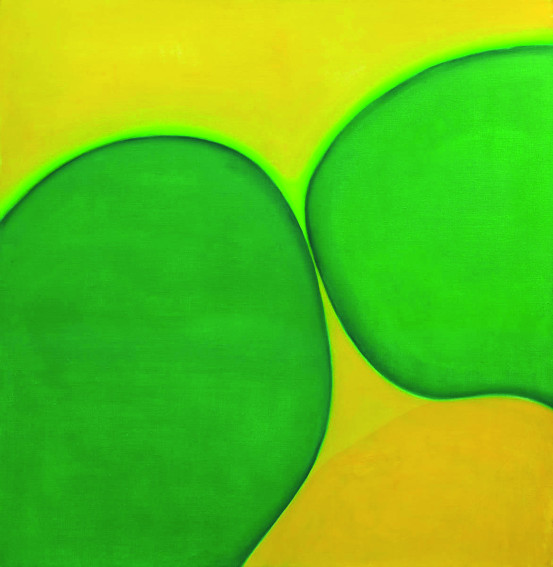

Huguette Caland - Bribes de corps, 1973. Courtesy the Caland Family. Photo Elon Schoenholz, Courtesy the Caland Family

What would you say is the tone you are hoping to set with this exhibition?

An explosion of joy and pleasure; an admiration and respect to all these artists; a consciousness of the long path in front of us to really deepen this history.

So many artists in this show have never received proper admiration and respect. Does it remain an alienating experience to be a female abstract artist today?

No, today we are not in a situation of alienation but of openness, of discovery and rediscoveries. The door is largely open, and many museums, art historians and young scholars are working to make a different future.

You undoubtably could have included many more artists in this exhibition. How did you narrow your selections?

It is such a complex process that I cannot describe it in few words. Availability of the works, cost of transportation, space issues, etc., are also a part of the final result. But I have realized a big part of what I wanted to make.

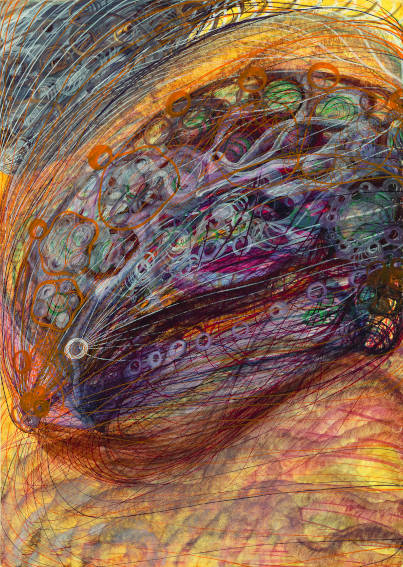

Georgiana Houghton - Album of Spirit Art, 1866-84. Image courtesy of The College of Psychic Studies, London

Were you afraid of omitting someone crucial?

It is less a fear than a certain sadness, a regret, sometimes, to be forced to choose. Omission is always part of the job, as history is always a partial story. This consciousness of the very impossibility of a total narrative is something that is at the core of research in general. Art history is always unfinished and rewritten. Nothing definitive, just a proposal.

You were an 8-year-old when you first visited Centre Pompidou. How would your perception growing up have been different if Elles font l’abstraction had been the exhibition on view during that visit?

It would have been a total different approach. It took a time to realize how art history was dominated by male art historians and artists. I remember clearly the artists I discovered when I went to the Pompidou as a child: Arman, Ben, John de Andrea, Jean Tinguely, all males! But as an adolescent I was very much into female writers: Anais Nin, Lou Andreas Salomé, Simone de Beauvoir, Marguerite Yourcenar, Marguerite Duras. I remember also reading Shere Hite, who was on the same shelf as Freud in the public library! That is why maybe as a student I decided to write my thesis on Rebecca Horn and translate all of her films from German into French.

To re-phrase the question you asked in 2017 as Director of the Visual Arts Sector of the Venice Biennale: What does it mean to be a female abstract artist today?

Actually, being an artist "tout court" should be the correct position. We are now over essentialism, hopefully. I never thought of myself as a “female curator.” As I used to say, nobody has actually asked Okwui Enwezor whether he was a father or married during his interviews as a director of the Venice Biennale. I found this very annoying to be always asked about my gender and so-called situation as a “woman,” instead of about my work. We need again a lot of research and exhibitions to arrive to this point for “women artists” as well. But the door is now wide open and there will be no step back thanks to the younger generation of art students.

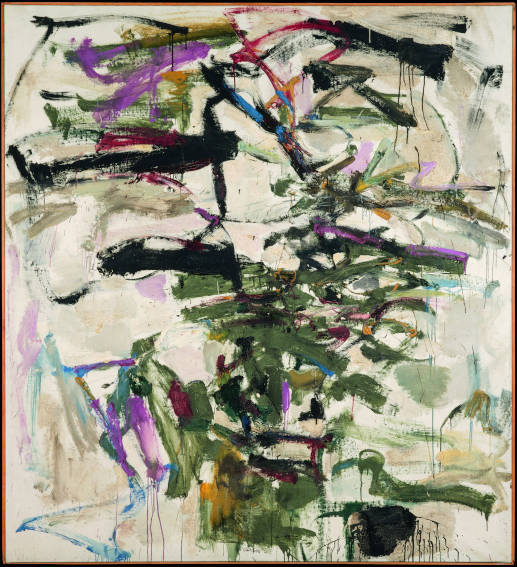

Joan Mitchell - Mephisto, 1958. © Estate of Joan Mitchell © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Jacques Faujour/Dist. RMN-GP

So your whole career you have been telling a more complete story of history. But abstraction is not about telling stories as much as it is about challenging perception. Does the appearance of this show at this time signal that you believe our generation needs to return to more esoteric pursuits?

No, I would not say that. But at the moment when people live with virtuality and images, in a parallel world, mostly figurative, I feel that the presence of abstract art leads us into a different sphere. It tells us about something both anchored into our cognitive and spiritual dimensions. You can feel very precisely what an abstract work tells you, whether it is materialistic or transcendental for example, whether it is funny or haptic, without any words. It is a bit like music. The perception is enough to get the points, and even to feel who is the artist behind it. In a moment where art is sometimes too much loaded by explanations and parallel discourses, I love to be with works that “speak” by themselves.

Our thanks to Christine Macel for generously granting IdeelArt this interview. Elles font l’abstraction is on view 5 May - 23 August 2021 at Centre Pompidou in Paris.

Featured image: Hilma Af Klint - The Swan, No. 16, Group IX/SUW, 1915. Courtesy the Hilma af Klint Foundation. Photo: Moderna Museet, Stockholm

All images used for illustrative purposes only

Interview by Phillip Barcio