Genius and Innocence: Rediscovering Karel Appel

Dec 29, 2015

IdeelArt recently had the opportunity to visit the Karel Appel exhibition currently on display at the George Pompidou Center in Paris. This was a great chance for us to rediscover the work of this important Dutch abstract artist. (Click here to see our Facebook album)

Whenever a discussion of abstract art arises, a refrain is eventually sounded that the work is open to interpretation. It is certainly true that much, if not all abstract work by definition defies simple, universal explanation by the viewer. But perhaps the question needs to be posed whether interpretation is possible at all, or whether it is even the point.

Karel Appel spent an entire lifetime engaged in the type of experimentation that intentionally sought to confound attempts at interpretive explanation. He went out of his way to seek ways of guaranteeing himself freedom of expression. For more than seven decades, he created imagery founded purely in the imagination. He went out of his way not to interpret his work. It makes us wonder: should we?

A Life of Free Expression

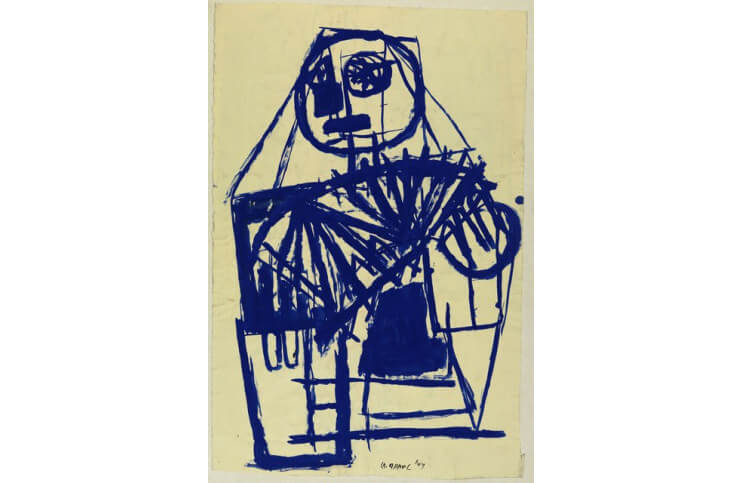

Appel painted his first work on canvas at the age of 14, in 1935. He died in 2006, after 71 years of making art. He has not had a major exhibition of his work in more than 25 years. Currently his works on paper are on display at the Pompidou Center in Paris. Appel's paper works are full of exhilarating motion and color. They're immediately recognizable for their playfulness, their nonjudgmental air and their childlike whimsy.

The Pompidou Center's retrospective includes 84 of Appel's works on paper. The collection ranges from 1947 all the way to 2006 and includes a large number of works that have never before been exhibited in public. Seeing this body of work on display all at once in a single viewing leads to the inescapable sense that the work communicates the overriding feeling of freedom which Appel so tirelessly sought.

We know that freedom of expression was of paramount importance to Appel because of his association with the CoBrA movement. CoBrA took root in the Netherlands during the German occupation of World War II. It derived its name from the hometowns of its founding members, which were Copenhagen, Brussels and Amsterdam. The movement was a reaction against other leading artistic movements of the time, such as Surrealism and Naturalism. The founders of the movement, of which Appel was one, turned to the creative expressions of children for their inspiration. Their groups's manifesto invokes childlike freedom in its argument in favor of unrestricted freedom in the use of form and color.

CoBrA only lasted a few years, but the members of the group carried with them their desire for artistic freedom and their lust for experimentation. Appel in particular pushed the boundaries of his work continuously. He traveled extensively, often continuously, and spent a great deal of time living, working and exhibiting alongside many of the famous American Abstract Expressionists. Throughout the many decades of his life, regardless of the changing tastes of the art world, Appel continued to explore his childlike freedom, evolving to work with glass, ceramic, sculpture, painting, drawing and any other medium he happened to find inspirational. He defied the trends, producing a profoundly prolific and unified body of work, actively working until his death in 2006 at age 85.

The Resurgence of CoBrA

The work of the CoBrA group has not been in favor for a long time with curators, dealers and collectors. But Appel's retrospective at the Pompidou Center is already creating renewed interest in the movement throughout the art world. Appel's works on paper reflect an undying sense of modernity. They reach out across decades, bridging multiple movements and tying them with the now.

When we at IdeelArt visited the exhibition we collected photographs of the work in order to create albums that will be viewable on social media platforms. What we found most exciting seeing all of these works together for the first time is the work's ability to appear simultaneously both innocent and mature. The collection has such undeniable weight to it as a whole, as do so many of the works individually. Yet many of the pieces, in their lightness of spirit, seem to almost lift off the paper.

We hope this retrospective of Appel's works on paper will lead to more exhibitions of his work in the near future. Until then, consider this anecdote making the rounds about Appel, especially in context of the recent resurgence of interest collectors are having in his work. Before Appel died, he set up a foundation dedicated to the preservation of his oeuvre. A large collection of the work disappeared while en route to the foundation. That missing work was rediscovered ten years later and returned to the care of the foundation. The mystery of who took the work has never been unraveled. But now that the art world is taking a fresh look at Appel's work, the thieves have new reason to regret their misadventure.

Photo Credit: Tom Haartsen Ouderkerk © Karel Appel Foundation / Adagp 2015