The Importance of “The Field”, Australia’s Landmark Exhibition, 50 Years On

Jun 15, 2018

Half a century ago, what would end up being the most influential Australian museum exhibition of the 20th Century opened at the brand new location of the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV). At the time, however, almost no one involved expected the show to make history. Titled The Field, the exhibition opened in a temporary gallery. It featured 74 works representing 40 artists, most of whom were less than 30 years old. The artists themselves were surprised, by and large, to have even been asked to exhibit at the NGV. The curators who organized the show assumed it would be little more than a showcase of what they saw as an emerging trend in Australian art. What happened instead is the Australian art media trashed the exhibition, ridiculing the art and declaring that the artists were of no value to Australia at all. The controversy inspired a great debate about the work. On one side was the established Australian art world, which overtly favored traditional figurative art styles. On the other side was a growing collective of artists, writers, and art lovers with an eye towards the rest of the world. Amazingly, many in Australia still look back at The Field with distaste, signaling that this debate still has yet to be resolved. Staking its ground firmly on the side of the curators who originally mounted the exhibition, the NGV recently opened The Field Revisited, a complete re-staging of the original exhibition in its entirety, presented for the consideration of a new generation.

The Power of Bad Criticism

The name of The Field was given as a reference to Color Field Painting, which by the late 1960s had become a dominant aesthetic position in the United States. Yet the title also referred to the idea that there was a much larger, expanding field of abstract concepts being pursued internationally, including Hard Edge Abstraction and Geometric Abstraction. It also referred to the growing field of Australian artists who were pursuing such international trends. All of the work in the show reflected the reality that Australia was part of a global movement towards innovative new aesthetic tendencies, and that those tendencies were decidedly abstract. Looking back today, it seems odd that such a premise would arouse controversy. After all, abstract art had been dominant in much of the rest of the world for decades by 1968. But the mainstream Australian art critics were fundamentalists who believed newfangled abstract creations had no business being called art.

Col Jordan - Daedalus - series 6, 1968, synthetic polymer paint on canvas. 164 x 170 cm. National Gallery of Australia, Canberra. Purchased 1969

To show just how extreme the critics were, The Guardian recently ran an article showing images of original works from The Field alongside actual quotes from the major Australian art critics from the time. One critic said, “the artists have nothing to say ... either about themselves or about their country.” Another said that exhibiting the work of these young, experimental artists was “like sending the college athletic team to represent Australia at the Olympics.” Among the more generous comments was one critic who called the work delightful, but then compared the exhibition to “a party where nothing is served but champagne. One soon begins to feel the need for something rather more substantial.” Such criticisms were not only in vain—they actually led to poor sales, and even caused some promising Australian abstract artists to feel defeated. One artist in the show, John Adam, responded to the critics by saying, “The real threat to the future of Australian painting is … that such vague, coloured emotional nonsense can be passed off as art criticism.”

Janet Dawson - Rollascape 2, 1968, synthetic polymer paint on composition board. 150.0 x 275.0 cm irreg. Art Gallery of Ballarat, Ballarat. Purchased with the assistance of the Visual Arts/Craft Board, Australia. Council, 1988 (1998.2). © Janet Dawson/Licensed by VISCOPY, Australia

The Hard Edged Truth

That legacy of shoddy art criticism re-emerged recently as a major source of concern for curators at the NGV when they first decided to try to re-stage The Field. They already knew that only a tiny handful of works from the original exhibition found buyers. The question they had to answer was how many works from the original show even still existed. Their investigation revealed a rather hard to swallow reality: 14 of the works from the original exhibition had been destroyed or lost. It may sound unbelievable that paintings and sculptures that were included in a major museum exhibition would have been so poorly cared for. Yet the hard truth is that since most of the artists who participated were young and had little resources, they had no choice but to either find places to store their works or get rid of them some other way.

Michael Johnson - Chomp, 1966, polyvinyl acetate on canvas. 122.0 x 305.5 cm. Private collection, Brisbane. © Michael Johnson/Licensed by VISCOPY, Australia

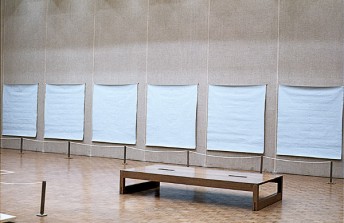

One particularly tragic story is that of Normana Wight, one of only three female artists who had their work in The Field. Wight created a massive, 3.6-meter grey painting for the show that, in pictures, declares itself as one of the most innovative works in the show. Nonetheless, it did not sell. Speaking to Sharne Wolff of Art Guide Australia, Wight explained that back in 1968 her studio was in her bedroom, and she had no money for storage. When the painting failed to attract a buyer, she “cut the work into 30cm squares,” and had the pieces burned. As tragic as that story is, however, at least Wight lived to see her work be appreciated at last. More than half of the artists in The Field, including some whose works were lost or destroyed, have already died. Those missing works are represented in The Field Revisited by silhouettes placed in the empty spaces where they were originally displayed. These silhouettes are reminders that art is not just a visual experience. Art museums are custodians of human culture. They have a responsibility to care for the human efforts they spotlight. And critics have a responsibility to avoid getting stuck in the past, or lashing out at what they clearly do not understand. The Field Revisited in on view at the NGV through 26 August 2018.

Featured image: Rollin Schlicht - Dempsey, 1968, synthetic polymer paint on canvas. 286.0 x 411.5 cm. Private collection, Brisbane © The Estate of Rollin Schlicht, courtesy of Charles Nodrum Gallery, Melbourne

By Phillip Barcio