The Week in Abstract Art - Why Do We Do It?

May 26, 2016

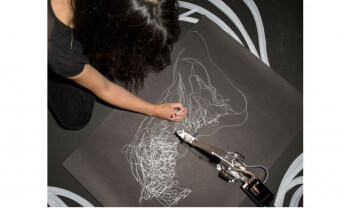

We saw two stories recently about computer programs making abstract art. One concerned a pinball-based video game in which the ball smashes digital paint blobs then tracks paint across the screen, creating an “abstract picture.” The other highlighted a “former painter” (not sure what that means) who fed a computer thousands of abstract art images then had it create its own images based on what it learned. Both stories said the computers were making “art.” But is that what art is? Output? True artists have motives. It isn’t only about what they do; it’s about why they do it. Here are some stories about true artists whose work isn’t only about the what, but also the why. Because sure, computers can imitate stuff humans do. The difference is, when we do it there’s a point.

Analyze This

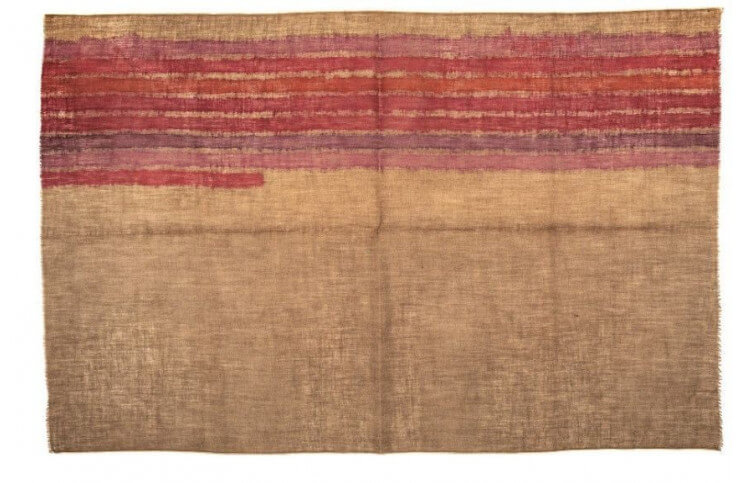

In the 1970s, a group of Italian artists embarked on a crusade to save painting. It was widely believed that through the various Abstract and Modernist art movements, painting had exhausted itself. Enter the Pittura Analitica movement, or Analytical Painting, which sought to break painting down to its essential elements once again, to understand its components and materials, and to contextualize the relationship paintings have to their creators. The movement gave painting a new breath of life. If you’ve never seen works by these artists, London's Mazzoleni Art has the work of 14 Pittura Analitica painters on view now through 23 July.

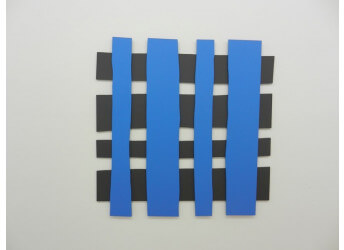

Patrick Heron - Six in Vermilion with Green in Yellow, 1970

Patrick Heron - Six in Vermilion with Green in Yellow, 1970

Creativity and Intention

Intellect isn’t the same as creativity. Imitating art others made isn’t the same as being an artist. Making art requires creativity and intention. The British painter Patrick Heron exemplified the right way to be inspired by other artists. In 1953, he wrote an essay detailing how non-figurative Parisian artists of the time were making the most important work since Cubism. Pierre Soulages, Nicolas de Staël and Hans Hartung taught him that an illusion of space existed within the materiality of a painting’s surface, something dismissed by previous abstract artists who focused on flatness. He said the materiality of paintings’ surfaces displayed “vibration of space.” A current exhibition of Heron’s abstract paintings borrows that phrase. Vibration of Space: Heron, de Staël, Hartung, Soulages is on view now through 9 July at London’s Waddington Custot Galleries.

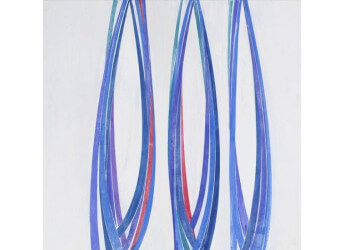

Robert Ryman - Untitled, 1958

Robert Ryman - Untitled, 1958

Right There In Black and White

Many humans bemoan monochromes, denouncing them as meaningless, easy, or even boring, proof that computers aren’t alone in underestimating art. (If we showed a computer a thousand monochromes, could it create one of its own?) Two New York exhibitions this summer challenge us to think more deeply about artists who choose to limit their color palette. Through 31 July, Dia: Chelsea presents a comprehensive exhibition showcasing five decades of Robert Ryman’s achromatic surfaces (what Google calls white paintings). And opening 23 June just three blocks north of Dia at PACE Gallery, the exhibition Blackness in Abstraction explores monochromatic black works curated from an “international and intergenerational” group of artists.

Could a computer be the next Robert Ryman or Patrick Heron? Is playing a video game the same as making art? Eventually we’re going to have to specify the differences between humans and machines. Art is the perfect field on which to explore this question. If a thousand artists painted a thousand white monochromes, maybe Google couldn’t explain the difference between them. But we know that even if paintings look similar, the difference is in their intent. Why did the artist do it? That’s always of interest. Because motive is what makes us human.

Featured Image: Giorgio Griffa - Linee Orizzontali, 1975, acrylic on canvas, 116 x 183 cm