Poetic Charge of an Abstract Print

Mar 3, 2016

At an opening of your favorite abstract painter’s work, you’re immediately drawn to a painting, like a happy moon being pulled toward a welcoming star. You know you want it. Then you see something written in the bottom right corner: 1/10. It’s not an abstract painting; it’s an abstract print. Your mind shifts. Questions of uniqueness intrude. It’s not a one-off; it’s one of ten. Should you still buy it?

Visual Poetry

Who can claim to understand a poet’s process? But we know this: Poets arrange words in abstract configurations in order to invite the unexpected in the mind of the reader. When we read a poem, as we attempt to comprehend what we’re reading, electrical activity increases in our brain. When we finally make a connection, and somewhere deep within our consciousness meaning is ascertained, our brain releases pleasure-inducing chemicals and we experience joy. We feel a sense of rhythm and beauty. That’s called poetic charge.

Abstract paintings are also said to possess a poetic charge. They are to imagery what poems are to words. When you look at an image of an apple, light hits the surface of the image and reflects back at your retina. Your brain analyzes the colors, shapes and lines as they come through the retina, and says “apple.” But when you look at an abstract image, though the same optical science occurs, at the end of the process your brain doesn’t know what to say. It scrambles to engage in neurological maneuvers in order to ascertain the conceptual meaning of the colors, shapes, and lines it sees. When it finally arrives at some inner sense of meaning from the image, rhythm and beauty come flooding in.

The question is, can an abstract print have the same effect? Can an abstract print possess the same poetic charge as an abstract painting? To find out, let's look at the differences between paintings and prints and consider the ways the brain might respond to each.

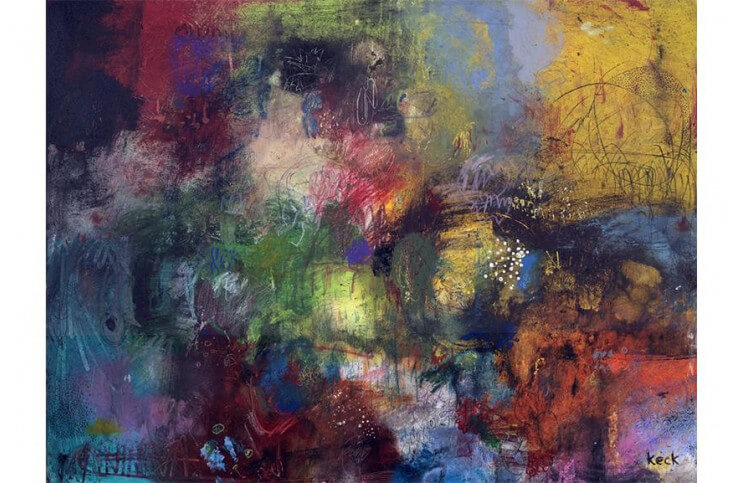

Clayton Kashuba - High Tade (detail), © Clayton Kashuba

Clayton Kashuba - High Tade (detail), © Clayton Kashuba

The Artist is Present

First of all, let's be clear that we are not talking about reproductions here. We’re not talking about mass-produced copies of original works of art. We’re also not talking about giclee prints with glaze brushed on them to make them seem like paintings, nor photographs of paintings made into posters. What we’re talking about here are artists’ prints: limited edition, hand-made multiples of an artist’s original work. Reproductions are just copies. Prints are considered unique, authentic works of art.

Artists’ prints are made in a number of different ways. They can be made from an engraving, like a woodcut. They can be made through lithography, which entails burning an image into metal or stone. They can be made by serigraphy, which is a fancy word for silk screening. Or they can be made by some variation of these methods involving the artist’s hand and some additional quasi-mechanical process.

When making prints from an engraving or a lithograph, each iteration of the print wears down the original plate slightly, subtly altering subsequent prints. When silk screening, the process involves the application of medium by the artist, and the application of pressure from the artist’s hand. This results in innumerable variations between prints due to inevitable deviations, environmental changes, or changes in the quality of the surface or the medium.

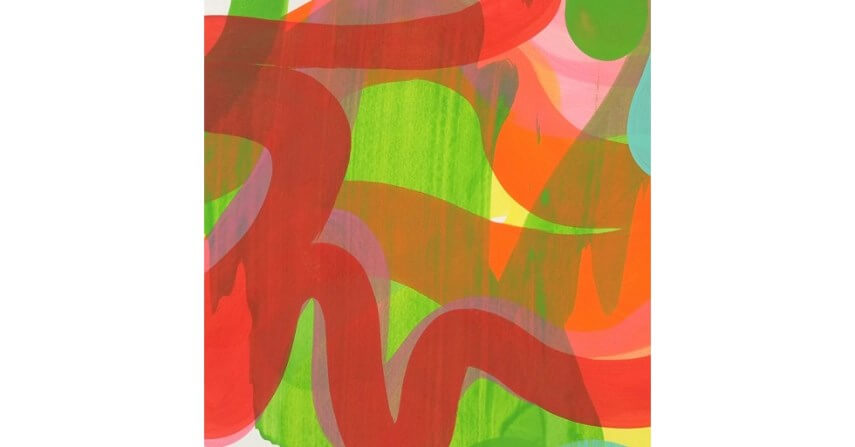

Matthew Langley - So Though, 2015, 22 x 28 in

Matthew Langley - So Though, 2015, 22 x 28 in

Uniqueness

What this all means is that artists’ prints are unique. They seem like they’re the same, but even if in the subtlest of ways, they’re not. This bodes well for the poetic charge of a print, since humans respond viscerally to things that are rare. If a viewer senses that more of something can be found elsewhere, an element of awe goes away.

Perhaps in this sense, a print might possess less potential for poetic charge than a painting, since a painting is a total one-off. However, since every print an artist makes varies from every other print due to the inevitable, inherent deviations in the process, as long as the series of prints is small enough, and the pool of buyers large enough, scarcity will still be created. And scarcity is a close enough substitute for rarity that it should give the print back whatever uniqueness it may have lost.

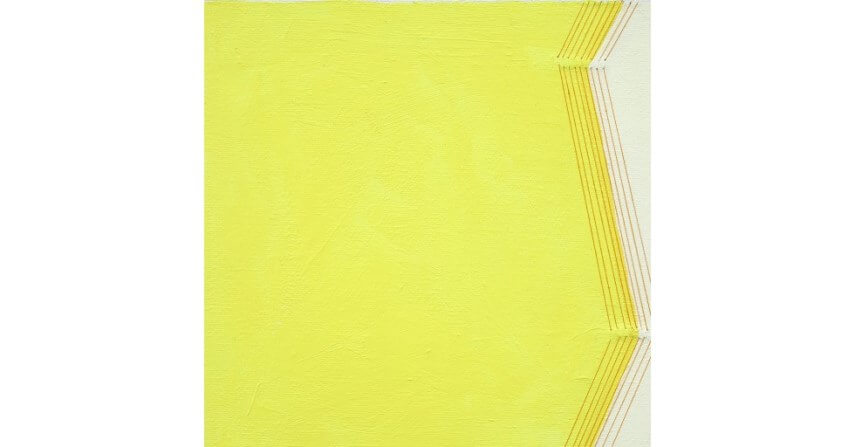

Margaret Neill - Groove 1, 2005, 22.8x22in

Margaret Neill - Groove 1, 2005, 22.8x22in

Medium Specificity

The human brain responds differently to different mediums because of the way various mediums interact differently with light. Oils reflect light differently than do acrylics or gouache. Watercolors reflect light differently than do charcoal or ink. Each medium also possesses other inherent physical qualities, such as viscosity, grittiness, or even aroma or taste from chemicals or metals in the medium. Each element of a medium’s essential qualities might potentially transfer meaning to viewers, thus affecting a work’s poetic charge.

But does medium specificity affect a print differently than it does a painting? Both paintings and prints are made with a medium. Both can be made with ink or paint or any other medium the artist can devise. What matters is whether the right medium is chosen for the right work. Prints involve different tools than paintings, so an inappropriate choice of the medium could interfere with the viewer’s connection to the work. As long as the appropriate medium is chosen, it shouldn’t affect the poetic charge of a print.

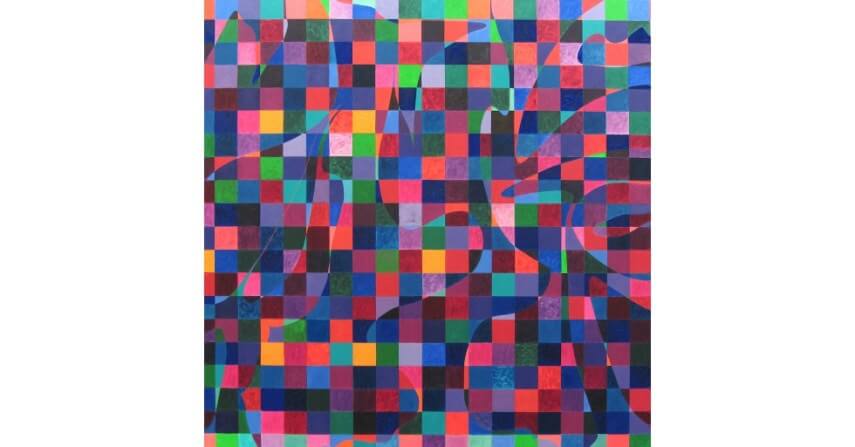

Jose Heerkens - L28. Passing Colours, 2012, 13.8 x 13.8 in

Jose Heerkens - L28. Passing Colours, 2012, 13.8 x 13.8 in

Flatness vs. Impasto

What might matter a lot is how the medium is applied. Each medium has a perceptible visual weight to it, and tactile qualities all its own. How it’s applied to a surface fundamentally alters how light reacts to it. The word impasto refers to the quality paint has when it’s glooped onto a painting’s surface. The texture and ridges paint develops as it’s layered onto a surface give it depth. The more the medium extends off the surface of the work, the more impasto, and the less flatness, the work has.

Since prints are made with the aid of a machine or other device, they do not posses impasto. The medium lays flat upon the surface and does not contain brush strokes. This flatness gives the work a look of mechanized perfection that is decidedly different from the “painterly” qualities of a work with impasto. But flatness should not reduce a print’s ability to possess a poetic charge. Flatness can be a highly desirable trait in a work of art. Flatness caused Clement Greenburg to tout the desirable traits of the post-painterly abstractionists. He praised them for the clarity of their images, which he felt was enhanced by their minimal “painterly” qualities.

Holly Miller - Bend #2, 2013, 9.8 x 9.8 in

Holly Miller - Bend #2, 2013, 9.8 x 9.8 in

On the Edge

When a painter is making a painting, the process often involves going beyond the edge of the surface, for example by dripping paint over the edge and onto the side of a canvas. That sense of imperfection can affect poetic charge by conveying passion, energy, or freedom, bringing additional layers of conceptual excitement to the work.

Prints are rolled out on flat surfaces in controlled ways. The process of making a print tends to result in clean edges and relatively precise corners. This look tends to convey more of a sense of control from the work than what would be communicated through a painting, but that doesn’t necessarily reduce the poetic charge of a print. It simply communicates something more subdued.

Dana Gordon - Night (detail), 2012, 59.8 x 78 in

Dana Gordon - Night (detail), 2012, 59.8 x 78 in

Below the Surface

Paintings generally begin with some kind of a primer surface, like a gessoed canvas or panel. This subsurface gives the painting an under layer that brings depth to the subsequent layers and hides the materiality of the surface. Additional under-layers can go on to add profound luminosity and value to the colors that end up comprising the final layer of a painting.

Prints are generally not composed of multiple layers of medium. Though some artists make prints with numerous layers of medium, often a print is made of a just a single layer printed onto a sheet of paper, or some other unprimed surface. This can give a print the sense of resting atop a surface rather than being incorporated into it. In this way, a print might lose some ability to draw a viewer in, since it could bring attention to the surface on which it rests.

Anya Spielman - Bloom, 2010, 7.9 x 5.9 in

Anya Spielman - Bloom, 2010, 7.9 x 5.9 in

Add it Up

A print and a painting share many similarities. They both use the medium to convey meaning. They can both possess medium specificity. But they also differ in important ways. Though unique, they’re differently unique. Prints also possess more flatness than paintings. They utilize fewer layers. They’re less painterly. In some ways, that enhances a print’s poetic charge. The colors can be more pure, more intense, maybe more modern. And who said modernity and poetry can’t mix?

We believe an abstract painting’s ability to affect a viewer is undeniable. And although different, why should an abstract print be less capable of touching someone in similar ways? When you’re thinking of buying a work of art, and you see that little 1/10, or 3/50, or 100/300 in the bottom corner of the image, just step back, clear your head then look back to the work. If what you see before you is beautiful, and your heart opens, that’s poetic charge. It’s a deluge: an outpouring. Celebrate that it’s coming from a print.

Featured image: Michael Keck - Running Free, © Michael Keck

Featured Artists

Matthew Langley

1963

(USA)American

Holly Miller

1958

(USA)American

Dana Gordon

1944

(USA)American

Anya Spielman

1966

(USA)American