Post-Painterly Abstraction - The Meaning and the Scope

Jun 20, 2016

In art historical terms, Modernism wasn’t a movement. It was more a process of art self-awareness. Rather than focusing on objective representation, Modernist painters explored what they could express through abstraction, or through painting’s formal qualities such as color, form, gesture and surface. Among Modernist painting movements, Post-Painterly Abstraction was one of the last to emerge before Post-Modernist attitudes gained prominence in the late 20th Century. It focused on painting’s most essential element—two-dimensionality, or flatness. It eliminated any reference to narrative subject matter as well as to the artist’s own personality. It achieved what the art critic Clement Greenberg considered the very point of Modernist painting, which was to reduce painting to it’s “viable essence.”

The Tenets of Post-Painterly Abstraction

To understand Post-Painterly Abstraction, it helps to consider its opposite: Painterly Abstraction, the perfect example of which is Abstract Expressionism . Imagine one of Jackson Pollock’s splatter paintings, with its primal energy and inherent drama. It’s an expression of Pollock’s subconscious self. Paint accumulates in layers and heaps, creating ridges and valleys. Detritus like glass and cigarette butts intermingles with the medium, creating a vivid, “painterly” work, where the artist’s hand, personality and ego are evident in every mark.

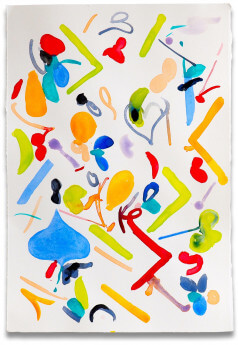

Helen Frankenthaler - Approach, 1962, Oil on canvas, 82 x 78 in., Anderson Collection at Stanford University, © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In a Post-Painterly Abstract painting there are no visible brush strokes. The surface of the painting is flat. Paint and surface are one. Colors are linear, not layered, and are also vivid and bright, expressive of their own essential qualities but nothing else. There are no details in the painting other than color, form and space. Rather than the composition telling a story or conveying subconscious drama, the composition is open, allowing the formal qualities of color and surface to be the subject of the work. A perfect example is Bridge, painted in 1964 by the American artist Kenneth Noland.

Kenneth Noland - Bridge, 1964, Acrylic on canvas, 89 x 98 in., © Kenneth Noland

Modernism vs. Post-Modernism

It potentially sounds confusing to call Post-Painterly Abstraction one of the last Modernist art movements. After all, there are many who believe Modernism is still going on today. Whether you consider yourself to be a Modernist or Post-Modernist basically boils down to what you believe. Post-Modernism considers history to be relative, and considers concepts of linear “progress” to be bunk.

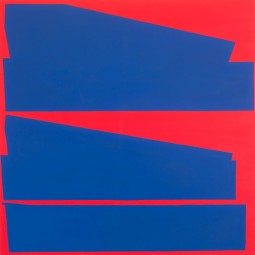

Jack Bush - Nice Pink, 1965, Acrylic on canvas, © Jack Bush

Modernism was based on the idea of a mutually agreed upon formal artistic past. Modernism demanded an artistic evolution. It demanded newness, which required invention, which in turn required an understanding of what had come before. In essence, Modernism tells a story. It says, “Artists used to do this until they started doing this,” and so on. In order to understand the contextual impact of any one work of Modernist art, you first need to understand why it was innovative for its time, which requires an understanding of its place within its particular movement as well as that movement’s place within the larger art historical narrative.

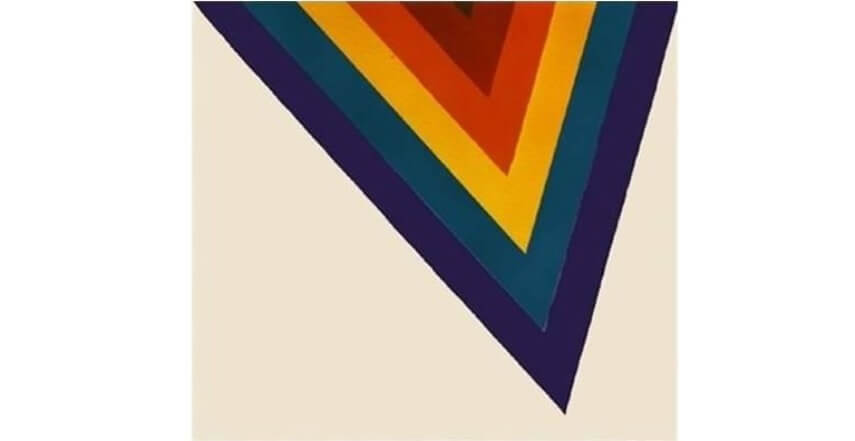

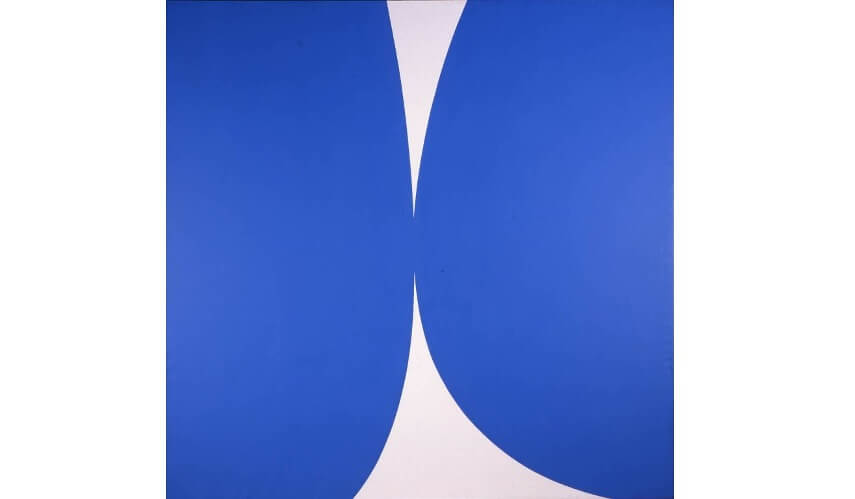

Ellsworth Kelly - Blue White, 1962, Oil on canvas, © Ellsworth Kelly

The 1964 Post-Painterly Abstraction Exhibit

The art critic Clement Greenberg was a true Modernist, meaning he believed in art history’s overarching narrative and felt a compulsion to contextualize contemporary tendencies in relation to that larger story. Greenberg’s sincerity and depth of historical knowledge made him one of Modernism’s most influential storytellers. Throughout the 20th Century, his extensive writings defined the Modernist narrative by describing its evolution from the mid-1800s on, contextualizing its advancements and even by naming its most well known, post-WWII movements, including Abstract Expressionism.

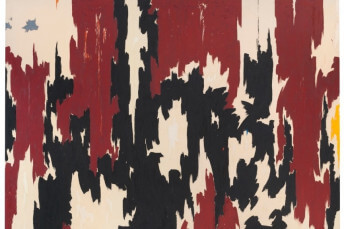

Morris Louis - Earth Gamut, 1961, Acrylic resin (Magna) on canvas, 86 7/8 x 60 in., Copyright © MICA / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Greenberg coined and defined the term Post-Painterly Abstraction by curating an exhibition with the same name at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1964. The LACMA Post-Painterly Abstraction exhibition featured the work of 31 artists, all of whom Greenberg considered to be making work representative of what he considered to be this new tendency in Modernist art. Among those included in the show were several artists who subsequently went on to become some of the 20th Century’s most famous painters, including Helen Frankenthaler, Jack Bush, Ellsworth Kelly, Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland and Frank Stella.

Kenneth Noland - Cadmium Radiance, 1963, Magna on canvas, © Kenneth Noland

The Stars of Post-Painterly Abstraction

Helen Frankenthaler contributed three works to the LACMA Post-Painterly Abstraction exhibition. Included was Approach, featuring Frankenthaler’s unique “soak stain” technique. This technique involved pouring thinned paint directly onto unprimed canvas in order to allow the medium to adopt organic forms while also eliminating brush strokes in order to minimize the appearance of the artist’s hand.

Jack Bush was a Canadian abstract painter associated with the group called Painters Eleven. The artists in Painters Eleven did not share a common style. Rather they were simply all devoted to making abstract work and supporting each other’s efforts. Clement Greenberg was an influential champion of the group, and took a particular interest in Bush’s work, encouraging him to continue refining and simplifying his colors and forms.

Ellsworth Kelly’s vivid, ultra-flat paintings incorporate an iconic visual language based on the distillation of shapes he observed in nature. In addition to his contribution to the advancement of Post-Painterly Abstraction, he also made an impact on Minimalism and Conceptual Art with his shaped, monochromatic works. Included in Kelly’s contribution to LACMA’s Post-Painterly Abstraction exhibition was the painting Blue White.

Like his contemporary Helen Frankenthaler, Baltimore-born Morris Louis poured paint directly onto unprimed canvas in order to avoid the appearance of brush strokes. His aesthetic incorporated vibrant, colorful bands of poured color, represented by the painting Earth Gamut, which was included in the LACMA exhibition.

For Kenneth Noland the objective of his work was to remove all semblance of emotion. He created an aesthetic vocabulary based on flat surfaces comprised of concentric circles and bands of color. His works were devoid of texture, revealing nothing of gesture or the artist’s hand. He is considered a pioneer not only in Post-Painterly Abstraction but also in ideas influential to Minimalism.

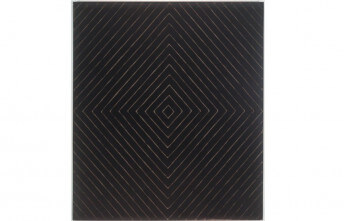

Still active today at age 80, Frank Stella has become one of contemporary abstraction’s most recognizable names. His efforts span multiple movements and defy categorization. Stella made his name with his early works in Post painterly Abstraction, and had three works included in the LACMA show. Among them was this piece, Henry Garden.

Featured Image: Frank Stella - Henry Garden, 1963, Oil on canvas, 80 x 80 in., Leo Castelli Gallery, New York, © Frank Stella

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio

Featured Artists

Joanne Freeman

1954

(USA)American

Holly Miller

1958

(USA)American

Ulla Pedersen

1967

(Denmark)Danish