AAA Stands for American Abstract Artists - Heralds of Abstract Expressionism

If you highly regard Rothko, appreciate Pollock, are crazy for de Kooning, frankly love Frankenthaler or are mad about Martin, get your party hat out. This year marks the 80th birthday of American Abstract Artists (AAA). Officially the 2nd AAA in the United States (the American Automobile Association was founded in 1902), American Abstract Artists organized in 1936 to combat mainstream resistance to abstract art in America. Since founding, the group has held hundreds of exhibitions and served as the theoretical and philosophical backbone for the development and preservation of American abstract art.

American Abstract Artists vs. MoMA

Years prior to 1936, a small group of what would eventually become AAA’s founders were regularly meeting at the residence of abstract sculptor Ibram Lassaw. The group was composed of artists who made what founding AAA member Esphyr Slobodkina called “the non-objective form of art.” They met to talk about their work and the philosophies behind it, and to discuss the difficulties they were having as abstract artists breaking into the American mainstream consciousness. In March of 1936, the MoMA held its first major exhibition of abstract Art. The show consumed four floors of the museum. Among the 400 artworks included in the show nearly all were made by European artists. A year earlier, the Whitney had held an exhibition of American abstractionists. The MoMA cited that show as a defense of their choice not to include Americans in their own exhibition. The artists who had been meeting at Lassaw’s home took offense to the slight, and officially formed the AAA.

Esphyr Slobodkina - Tubroprop Skyshark, 1950, Oil on masonite, 16 3/4 x 20 3/4 in, © Slobodkina Foundation

Show and Tell

The goals of the AAA were two: first, they wanted to give American abstract artists opportunities to exhibit their work to the public; second, they wanted to develop a theoretical foundation for the validity of abstract art that would resonate with American critics and the public. The first exhibition held by AAA was in 1937. It was generally derided by critics, but more than 1500 people came to the show, demonstrating powerful, latent public interest in the work. The group held seven exhibitions in 1938: three in New York, plus a traveling exhibition that went to Seattle, San Francisco, Kansas City, MO, and Milwaukee. Meanwhile, the members shared their thinking through lectures, panels and by publishing their writings. What began as casual conversations in those early meetings at Lassaw’s home led to a number of concise statements that expressed the enduring philosophy and principals of American abstract artists. Wrote Ibram Lassaw in 1938, “The artist no longer feels that he is ‘representing reality,’ he is actually making reality. Reality is something stranger and greater than merely photographic rendering can show.”

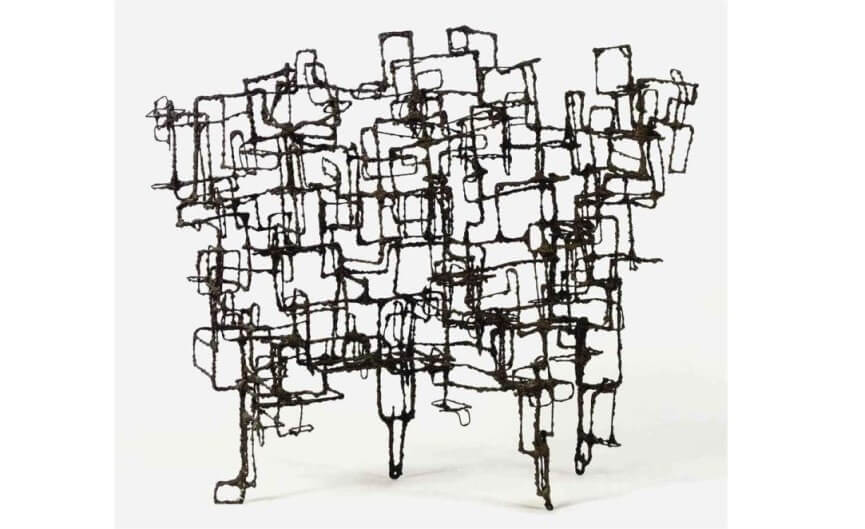

Ibram Lassaw - Coma Berenice, 1952, Bronze, 65 x 75 x 40 cm.

Roll Call

In addition to Ibram Lassaw and the fore mentioned Esphyr Slobodkina, who was an influential illustrator, painter and teacher, the AAA’s founders included many who have come to be recognized as influential American abstract artists. Among them: Bauhaus alumni, “Homage to the Square” painter, and teacher of Robert Rauschenberg , Josef Albers; Abstract Expressionist painter John Opper; painter, teacher and one-time Director of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Burgoyne Diller; abstract painter, teacher, and star student of Hans Hofmann, Rosalind Bengelsdorf; and art writer, illustrator and painter Ilya Bolotowsky. As Director of the WPA, Burgoyne Diller played a particularly important role in the survival of several artists in the AAA. The WPA was a Depression-era, federal New Deal program designed to provide employment to millions of out of work American laborers. Their mural program was the first major attempt by the American government to fund the creation of public artwork. Diller and fellow AAA founder Louis Schanker, who was also an administrator with the WPA, made sure many struggling abstract artists found paying jobs with the WPA painting public murals.

Louis Schanker - WNYC Radio Station mural, 1939

Rise of the New York School

The efforts of the AAA were vital to helping turn New York City into the center of the American modern art scene. After World War II, scores of AAA members and their colleagues lived in close proximity to each other in New York. Many even spent summers near each other on Long Island. Together they were engaged in a common search for new ways to express the anxiety and character of their time, an era marked by war, atom bombs, famine and massive global industrialization. The work these post-WWII New York abstractionists were making was far different than what the public had gotten used to. Though the AAA had been successful in helping abstract art gain acceptance among American critics and audiences, it was mostly only a certain type of abstract art that was being embraced, work possessing what the abstract painter and Bard College professor Stephen Westfall calls “a dynamic, geometric clarity.” As Westfall puts it, abstract art “had come to be equated with the clean lines and aesthetic pragmatism of the machine-age.”

Clyfford Still - PH-1082, 1978, oil on canvas, © Clifford Still Museum

Clyfford Still - PH-1082, 1978, oil on canvas, © Clifford Still Museum

AAA + AbEx

The AAA encouraged and supported diversity among abstract artists. Wrote Lassaw: “We must make originals. All aesthetic phenomena produced by artists belong to the field of art, whether they fit into the former concepts and definitions or not.” As the new generation of New York abstract artists frantically pushed the boundaries of their work, exploring the subconscious and seeking more intuitive ways to paint, the AAA gave them practical and theoretical support. Without the AAA’s support it is unlikely the Abstract Expressionists would have gained the traction and momentum that helped them change the world of modern art. Among these artists whose controversial works needed occasional defending and explaining from the AAA were Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Clyfford Still, Willem de Kooning and Barnett Newman, all of whom eventually became associated with Abstract Expressionism. The art critic Clement Greenberg, who championed the work of the Abstract Expressionists, was also a member of the AAA, as was the Abstract Expressionist painter Lee Krasner, wife of Jackson Pollock.

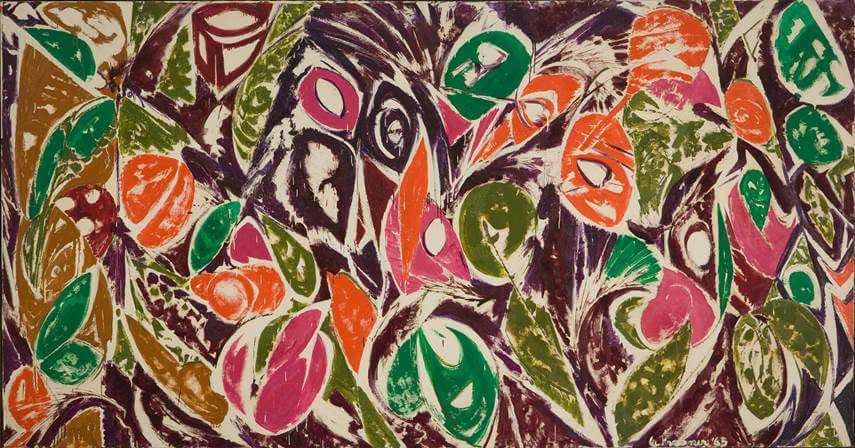

Lee Krasner - Right Bird Left, 1965. David Owsley Museum of Art

Lee Krasner - Right Bird Left, 1965. David Owsley Museum of Art

The AAA Today

In its contemporary form, the AAA has dual roles. First, it continues to support the activities of American abstract artists. Second, it works to protect the legacy of American abstraction’s past. The AAA advocates on behalf of preservation of works, and continues to provide an intellectual and theoretical basis on which abstract artists might build. As the Italian-born, American abstract artist Lucio Pozzi wrote in 2010, “AAA has become the field where personal sensibility and intellectual discourse are freely cultivated with no end in sight…the sheer persistence of these artists, each in his or her concentration, is now the beacon of the creative present.”

Feature Image:Clyfford Still - PH-401 (detail), 1957, Oil on canvas,© Clyfford Still Museum

All images used for illustrative purposes only