Frank Stella - the Art of Object

Many bemoan the apparent oncoming death of printed books. But the function of books is to tell stories, and apparently screens and disembodied voices tell stories just as well. Since books as objects have never been separated from their storyteller role, they’ve outlived their use. Thanks to Frank Stella, art will not face the same fate. Stella divorced art from its narrative purpose. Rather than allowing painting and sculpture to continue functioning as they had for centuries as delivery devices for illusion, Stella played a key role in redefining art, bestowing upon it objective meaning and purpose. Through his aesthetic creations, Stella demonstrated that an art object is worthy of consideration not for the story it might tell or for the interpretation it might contribute to, but for its own formal aesthetic qualities and the satisfaction they might provide.

Frank Stella Art vs. Abstract Expressionism

Had the young Frank Stella been in better health he may never have become a famous artist. After graduating from Princeton, Stella was drafted to fight in Vietnam. But he failed his physical. So rather than fighting actual battles overseas he joined the cultural battle in his homeland, striving against the prevailing art movement of the time: Abstract Expressionism. Said Stella about the Abstract Expressionists, “(They) always felt the painting’s being finished was very problematical. We’d more readily say that our paintings were finished and say, well, it’s either a failure or it’s not, instead of saying, well, maybe it’s not really finished.”

Stella felt that Abstract Expressionist artists and their admirers were attributing “humanistic” qualities to art, meaning that they looked for more in the art than what was objectively there. Certainly he was correct that many abstract artists then, as now, openly believe that their work is open to interpretation. For many abstract artists that’s the point. They even offer their works up as totems, or as transcendental mediums to be utilized in the search for heightened experiences. In fact, many art lovers derive an immense amount of satisfaction interpreting what abstract paintings could possibly mean. But Stella wanted none of that kind of interaction to occur between his work and its viewers, leading him to make his most famous statement about his art: “My painting is based on the fact that only what can be seen there is there. It really is an object. What you see is what you see.”

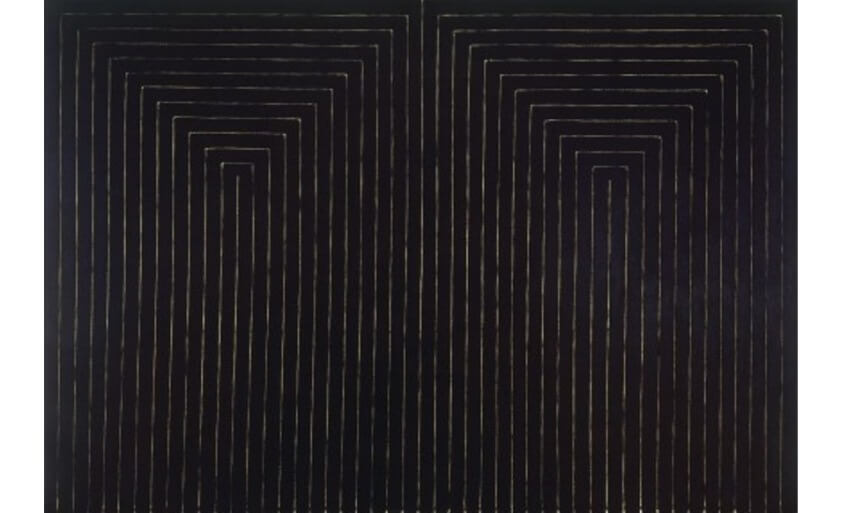

Frank Stella - The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II, 1959, Enamel paint on canvas, 91 x 133 in. © Frank Stella

Stella’s Two Problems

The first problem Stella identified with his desire to reduce painting to its objective essence was to discover what exactly a painting is. To follow him down his path of reasoning, it’s helpful to first identify what he believed that a painting is not. He believed that a painting should not be a delivery mechanism for narrative. Nor should it be an arena in which to demonstrate or experience drama or illusion. So what should a painting be in Stella’s opinion? It should be a surface covered in paint. It should be an assortment of parts, which include the support for the surface, the surface itself, the devices connecting the surface to the support, the devices connecting the total object to the wall or the floor, and of course the medium.

Once Stella understood that for him a painting was an object, and nothing more, his next problem was determining how to make one. That second question is one that he has endeavored to answer repeatedly throughout his career, and one that he has addressed in a number of different ways. Still active today in his 80s, Stella has continually sought new methods of making paintings. He has made paintings on traditional, rectangular canvases, paintings on differently shaped canvases, murals, prints, three-dimensional relief paintings and paintings that many people would describe as sculptures.

Though some of Stella’s works do seem to fit the traditional definition of sculpture, Stella finds that distinction to be irrelevant. He has commented to the effect that sculptures are only paintings that have been taken off the wall and set on the ground. His so-called sculptural works are surfaces covered in medium attached to supports, same as his paintings. By maintaining this critical stance, Stella forces us to confront the notion of why exactly paintings are defined as things that must hang on a wall. Like many other conceptual leaders, Stella understands painting and sculpture to be the same thing, simply displayed differently.

Frank Stella - La Pena de Hu, 1987-2009, Mixed media on etched magnesium, aluminum and fiberglass. © Frank Stella

The Purpose of Geometry

As Stella searched for ways to make paintings without emotion, narrative or drama, he found himself drawn to patterns and to repetition. Geometric symmetry was helpful to him because, as he put it, it “forces illusionistic space out of the painting at constant intervals by using a regulated pattern.” He relied on this simple approach to make some of his earliest and most beloved works, his iconic “black paintings,” such as The Marriage of Reason and Squalor, II. These works presented flattened surfaces completely covered in black paint with the addition of geometrically symmetrical white lines.

Stella’s Black Paintings made him instantly famous when they were first shown. They weren’t the first mostly black abstract paintings in the history of Modernist art. They also weren’t the first geometric abstract works, or the first flat surface paintings. What made them groundbreaking was their utterly objective presence. They were not in the least open to any type of interpretation. There was no content. They were simply aesthetic objects, demanding to be considered according to their own formal, objective qualities. Rather than experiencing transcendence from something hidden within the painting or from some interpretive element in the work, the only transcendent experience Stella intended for viewers of these paintings to have came from the psychological relief of being allowed to interact with an aesthetic object on its own terms.

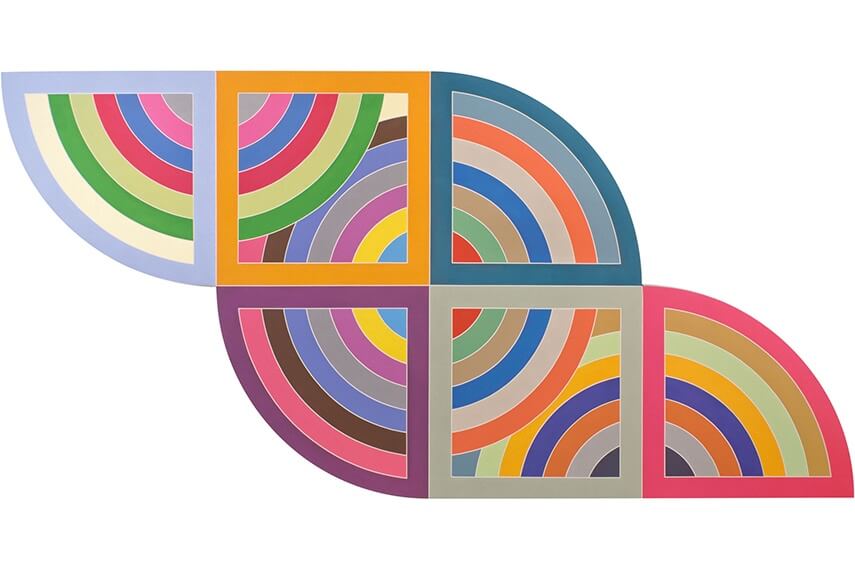

Frank Stella - Harran II, 1967, Polymer and fluorescent paint on canvas, 120 × 240 in. © Frank Stella

A Lifetime of Experimentation

After gaining fame in the 1950s with his Black Paintings, Stella added a vivid color palette to his works and began shaping his canvases in order to be able to create painted forms without causing the presence of unused surface. Over the coming decades, he continued to challenge the boundaries of aesthetic space, creating paintings that presented three-dimensional reality as a tactile, objective thing rather than an illusion.

Though Stella’s extensive and multi-faceted body of work has evolved many times, it has always reflected his core belief in art as object. His efforts have been a major influence on movements as far ranging as Post-Painterly Abstraction, Minimalism, Pop Art and Op-Art. The legacy of his thinking is that we know the precious essence of being in the physical presence of a unique work of art. A photograph of a Stella work is inadequate. Only the object itself suffices. Whether we like the work or not is irrelevant. The work itself is undeniable.

Featured Image: Frank Stella - Jill, 1959, Enamel on canvas, 90 x 78 in. © Frank Stella

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio