Art Informel - The Painterly Reflection of Post-War Europe

Apr 5, 2016

The artists associated with Art Informel are sometimes called the international equivalents of the Abstract Expressionists. Coming to prominence in the years following World War II, they rejected pre-War art logic and made paintings from improvisation and experimentation. But unlike Abstract Expressionism, Art Informel wasn’t so much an art movement as it was an umbrella term for a number of loosely related art movements, all of which had one thing in common: the rejection of reason in favor of intuition.

Painting Minus Logic = Art Informel

People today look back at World War II as a just war in which clear divisions existed between good and evil. The horrors suffered by both sides are often validated because the good guys won in the end. But to understand the rise of Art Informel, we need to enlarge our view. Human beings guided by logic and reason caused World Wars I and II, the Great Depression, global famine, genocide, and atomic warfare. The logic of civilization is that it requires security, which requires power, which to be believed must be asserted.

After World War II ended, the scientist J. Robert Oppenheimer, who had contributed immensely to the creation of the atomic bomb, said, “We knew the world would not be the same.” That was common attitude among artists at the time as well, that historical logic is what had gotten the world into its tragic mess and that everything had to change. Many embarked on a quest for something deeper than logic that could guide their art. Seeking something to which all humans could relate they abandoned form. They abandoned planning. For the first time in art history, rather than beginning with an idea and then finishing with a painting, painters simply began painting, guided by instinct, letting their gestures, mediums and subconscious feelings guide their creations. Only when their works were finished did they venture to assign them meaning.

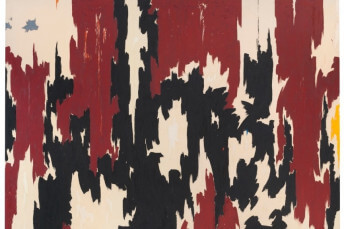

Georges Mathieu - The Battle of Hastings, 1956, © Georges Mathieu

Georges Mathieu - The Battle of Hastings, 1956, © Georges Mathieu

The Magic Tache

In the United States, the trend toward a subconsciously guided, instinctive art culminated in the rise of what became known as Abstract Expressionism. Internationally, and especially in Europe, it resulted in a variety of different movements, including CoBrA, Lyrical Abstraction and Art Brut. Each of these movements can be arranged under the larger heading of Art Informel, as each in some way embraced a rejection of prior artistic logic in lieu of something more primal, more subconscious, and more instinctive. The most successful and influential among the Art Informel movements was called Tachisme. The origin of the word Tachisme is the French word tache, which means stain. Tachisme is characterized by many of the same elements associated with Abstract Expressionism, such as paint splatters, drips, spontaneous brush strokes, primal techniques such as scratching the surface with knives, fingers, sticks and other tools, burning, slicing or otherwise damaging the canvas, or any other gesture inspired by the artist’s intuition.

Jean Fautrier - La Juire, 1943, 65 x 73 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

Jean Fautrier - La Juire, 1943, 65 x 73 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris

The Leading Figures of Art Informel

Truly a global phenomenon, the key figures of Art Informel hailed from many countries, including France, Italy, Germany, Spain and Canada. In France, the leading painters associated with the tendency were Pierre Soulages, Jean Fautrier and Georges Mathieu.

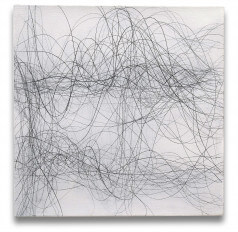

Pierre Soulages

Pierre Soulages was well known for his powerful, confident gestures and his simplified improvisational aesthetic. He became known as the “Painter of Black” due to the special attention he gave to what he called the “color and non-color” of black, which he considered a source of illumination.

Pierre Soulages - Painting, 25 February 1955, 1955, Oil on canvas, 100 × 73 cm

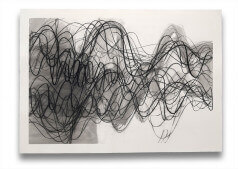

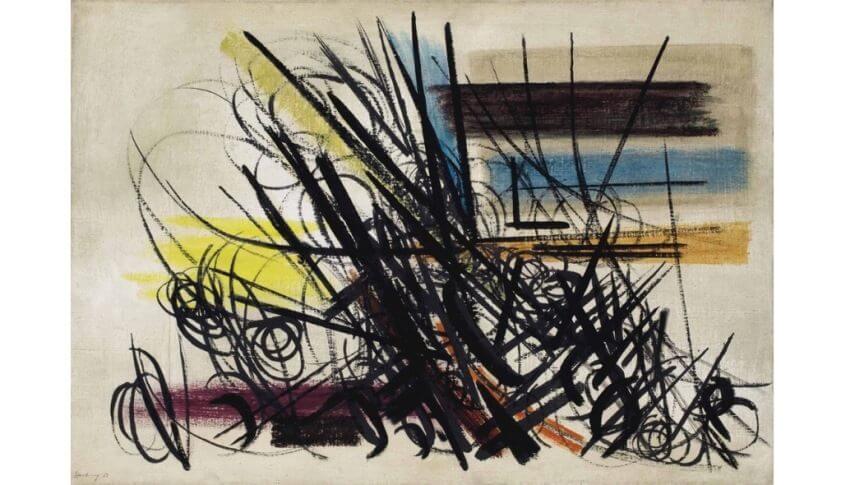

Hans Hartung

From Germany came Hans Hartung, one of many artists who were labeled “degenerate” by the Nazis. Hartung fled his native country for France in 1935. He enlisted in the French Foreign Legion and fought in North Africa during World War II, losing his right leg in battle.

Hans Hartung - T1950-43, 1950, Oil on canvas, 38 x 55 cm, © Hans Hartung

Emilio Vedova

In Italy, Art Informel was widely embraced, giving rise to the careers of artists like Alberto Burri and Emilio Vedova. Vedova went on to become one of Italy’s most influential modern painters. In addition to being a leading figure in Art Informel, he exerted a tremendous influence on the Arte Povera movement and achieved global recognition. Vedova was supported and collected by Peggy Guggenheim and he won the Grand Prize for painting at the 1960 Venice Biennale.

Emilio Vedova - Ciclo 61N.8, 1961, Oil and collage on canvas, 146.5 x 200 cm, © Emilio Vedova

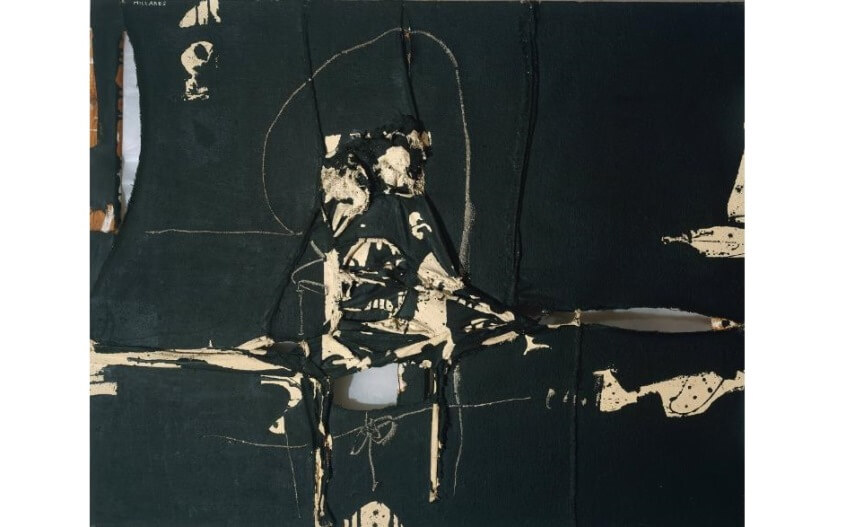

Manolo Millares

From Spain came the self-taught painter Manolo Millares, who transitioned to Informalism from Surrealism, attaining global recognition in the early 1960s. Millares incorporated a vast range of mediums and techniques into his works, including the slashing of his surfaces and the addition of collage elements using discarded cloth and other found materials.

Manolo Millares - Painting 150, 1961, Oil paint on canvas, 1308 x 1622 mm, © The estate of Manolo Millares

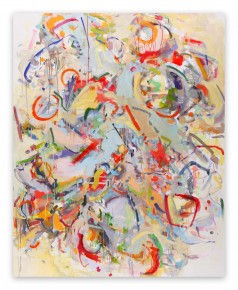

Jean-Paul Riopelle

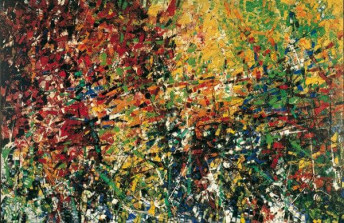

From Canada came the painter Jean-Paul Riopelle, considered the most successful Canadian abstract artist. Riopelle spent most of his productive years living in France, and was the long-time companion of the American Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell.

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Epiphanie, 1956, Oil on canvas, 29 x 39 in, SODRAC Succession Riopelle

Automatic Improvisation

The unifying, driving force that guided all participants in Art Informel was what the Surrealists called automatism: actions without conscious premeditation. Perhaps underlying their efforts was a desire to purge themselves of images that resided within their subconscious; images dominated by scenes of carnage and destruction. Perhaps this way of making art helped the entire culture to re-imagine civilization through a return to primitivism. But what was most consequential about Art Informal was its aspect of improvisation. It was pure personal expression. It elevated the importance of the individual artist. It valued self-discovery, and encouraged viewers to interpret the work, offering them a chance to discover themselves as well.

Because the artworks connected with Art Informel were so intimately connected to the inner psychological workings of the individual artists who made them, they can be seen as truly humanistic. They elevate the precious nature of the individual above all else. After decades of so-called civilization doing everything in its power to make individuals feel worthless except as bullet sponges, workers, corpses and tools, the artists of Art Informel reversed the tide, returning individual creative dignity to a world in desperate need.

Featured Image: Jean-Paul Riopelle - Composition (detail), SODRAC Succession Riopelle

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio