Defining the Lyrical Abstraction

Lyrical Abstraction is a seemingly self-defining term, and yet for generations its origin and meaning have been debated. The American art collector Larry Aldrich used the term in 1969 to define the nature of various works he had recently collected that he felt signaled a return to personal expression and experimentation following Minimalism. But the French art critic Jean José Marchand used a variation of the term, Abstraction Lyrique, decades earlier, in 1947, to reference an emerging European trend in painting similar to Abstract Expressionism in the US. Both uses of the term referred to art that was characterized by free, emotive, personal compositions unrelated to objective reality. But those tendencies can be traced back even farther still, at least to the first decade of the 20th Century and the work of Wassily Kandinsky. To uncover the true roots and meaning of Lyrical Abstraction, and to understand how to interact with its tendencies in art, we have to look to the earliest days of abstract art.

Putting the Lyrical in Lyrical Abstraction

In the 1910s, several different groups of artists were flirting with abstraction, each from a unique perspective. Cubist and Futurist artists were working with imagery from the real world and altering it in conceptual ways to express abstract ideas. Suprematist and Constructivist artists were working with recognizable forms in their art, but using them in ambiguous or symbolic ways, or in a way that attempted to convey universalities. But another group of artists was approaching abstraction from a completely different perspective than the rest.

Epitomized by Wassily Kandinsky, this group approached abstraction from the perspective that they did not know what meaning there might be in what they painted. They hoped that by simply painting freely, without preconceived notions of aesthetics or the objective world, something unknown could be expressed through their work. Kandinsky likened his paintings to musical compositions, which communicated emotion in a completely abstract way. His abstract paintings were imaginative, emotive, expressive, personal, passionate and completely subjective; in other words, lyrical.

Wassily Kandinsky - Composition 6, 1913. Oil on canvas. 76.8 × 118.1" (195.0 × 300.0 cm). Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Wassily Kandinsky - Composition 6, 1913. Oil on canvas. 76.8 × 118.1" (195.0 × 300.0 cm). Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

Post-War Lyrical Abstraction

The Lyrical Abstraction of Kandinsky contrasted with many of the other abstract art tendencies of the 1920s and 30s. His art was not specifically associated with any religion, but there was something overtly spiritual to it. Other artists associated with styles like De Stijl, Art Concrete and Surrealism were making art that was secular and lent itself to objective, academic interpretation. Kandinsky was seeking something that could never be fully defined or explained. He was expressing his personal connection with the mysteries of the universe in an open way. It was like he invented a kind of spiritual Existentialism.

Existentialism was a philosophy that came to prominence after World War II, when people were struggling to understand what they perceived to be the meaninglessness of life. Critical thinkers could not believe that a higher power could exist that would allow the kind of destruction they had just witnessed. But rather than becoming nihilistic in the apparent absence of god, the Existentialists attempted to work their way through the overarching meaninglessness of life, by seeking personal meaning. As the existentialist author Jean-Paul Sartre wrote in his book Being and Nothingness in 1943, “Man is condemned to be free; he is responsible for everything he does.” The search for what is essentially personal was paramount to Existentialism, and also to the widespread re-emergence of Lyrical Abstraction after World War II.

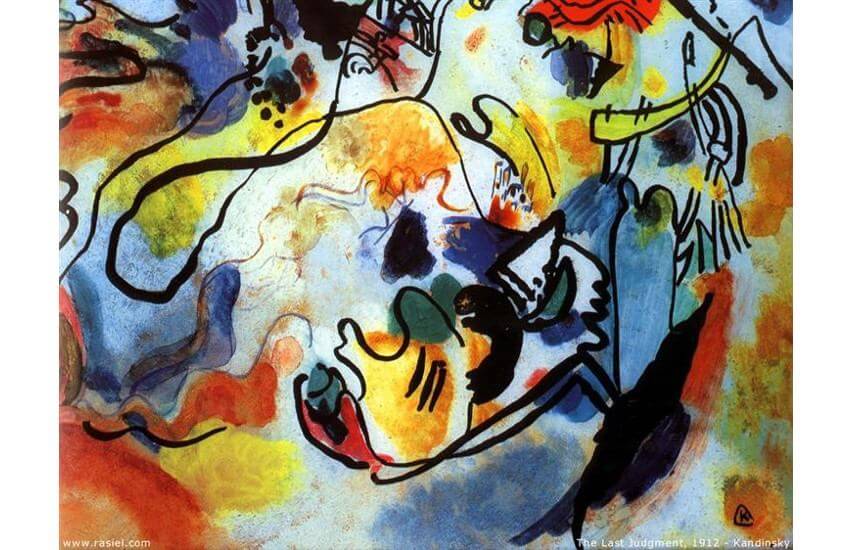

Wassily Kandinsky - The Last Judgment, 1912. Private collection

Wassily Kandinsky - The Last Judgment, 1912. Private collection

By Any Other Names

Throughout the 1940s and 50s, a great number of abstract art movements emerged that all in one way or another involved subjective personal expression as the foundation for expressing meaning in art. Abstraction Lyrique, Art Informel, Tachisme, Art Brut, Abstract Expressionism, Color Field art, and even conceptual and performance art all, to some degree, could be traced back to the same general existential quest. One of the most influential art critics of this time, Harold Rosenberg, understood this when he wrote, “Today, each artist must undertake to invent himself...The meaning of art in our time flows from this function of self-creation.”

But as the culture changed with the next generation many of these existential tendencies in art fell out of favor. And once again an unemotional, concrete, geometrical approach to abstract art, epitomized by Minimalism, took their place. But not all artists abandoned the lyrical tradition. By the end of the 1960s, the tide had once again turned. As was pointed out by Larry Aldrich, who re-coined the term Lyrical Abstraction in 1969, “Early last season, it became apparent that in painting there was a movement away from the geometric, hard-edge, and minimal, toward more lyrical, sensuous, romantic abstractions in colors which were softer and more vibrant…The artist’s touch is always visible in this type of painting, even when the paintings are done with spray guns, sponges or other objects.”

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Composition, Oil on canvas, 1954. © Jean-Paul Riopelle

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Composition, Oil on canvas, 1954. © Jean-Paul Riopelle

Contemporary Lyrical Abstraction

It is apparent that, as is often the case with movements in art, the tendencies that define Lyrical Abstraction pre-dated the coining of the term. In the first decades of the 20th Century artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Alberto Giacometti, Jean Fautrier, Paul Klee and Wols first embodied lyrical tendencies in abstraction. And decades later artists like Georges Mathieu, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Pierre Soulages and Joan Mitchell next carried them forward. Then in the late 1960s and 70s, artists like Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski, Mark Rothko and dozens of others revitalized and expanded the relevance of the position.

In 2015, one of the most fascinating voices in contemporary Lyrical Abstraction, the Spanish artist Laurent Jiménez-Balaguer, passed away. But its concepts, theories and techniques continue to manifest in powerful ways today in the work of such artists as Margaret Neill, whose instinctive compositions of lyrical, intertwined lines invite the viewer into a subjective participation of personal meaning, and that of Ellen Priest, whose work brings alive her lifelong and ongoing, personal aesthetic conversation with jazz music. What holds all of these artists together in a common bond is the fundamental quest of Lyrical Abstraction: to express something personal, subjective and emotive, and to do it in a poetic, abstract way.

Ellen Priest - Dolphin dance study 15.

Ellen Priest - Dolphin dance study 15.

Featured image: Margaret Neil - Switchback (detail).

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio