Alberto Burri and the Transformation of Materials

If we say a work of art has meaning that implies we believe meaning exists. But if meaning exists, shouldn’t life itself be the most meaningful thing? After all, it’s only because we’re alive that we can enjoy pondering the meaning of other things. Alberto Burri became an artist during a time of paradox regarding meaning. He started painting as a prisoner of war during World War II. He had been a doctor before the war, and served on the front lines in the Italian infantry, and as such had witnessed firsthand the conclusion civilization had evidently come to regarding the apparent meaninglessness of human life. Yet at the same time, artists in Europe and America were throwing themselves headfirst into modes of expression that were entirely about personal meaning: unconscious meaning, psychological meaning, hidden meaning and universal meaning. Somehow society was holding two opposite thoughts: that a living thing can have such little meaning that it can be wasted in war, and that an inanimate object can possess such meaning that it can become priceless. Burri’s work, at least in part, addresses his feelings about what should and does have meaning. By considering it closely we can perhaps arrive at some of what this unique artist uncovered; truths that might increase our understanding of abstract art and ourselves.

Alberto Burri’s Roots

In a sense, without war maybe Alberto Burri wouldn’t have become an artist. He would have become a country doctor instead. Burri was born in a small town in Umbria, Italy, in 1915, to a father who sold wine and a mother who taught school. The countryside of his home is idyllic. Its landscape would eventually serves as subject matter for many of Burri’s first paintings, the ones he taught himself to paint as an American prisoner of war in Texas. In 1940, Burri graduated university with a medical degree. He had just begun o practice as a medical doctor when later that same year Italy entered World War II. Burri was drafted into the infantry. For nearly three years he fought as a frontline soldier in North Africa, also serving as a physician in the field.

When Burri’s unit was captured, he was sent to a prisoner of war camp in Hereford Texas. There, Burri wasn’t allowed to practice medicine. So like many other POWs he took up painting to pass the time. Lacking proper canvases he painted on burlap sacks. He painted idyllic landscapes of what he saw in Texas, and of what he had seen earlier in life, in Umbria. After the war, upon being repatriated to Italy, Burri abandoned medicine forever, throwing himself completely into his art. But he took his aesthetic in a much different direction. He reduced his visual language, creating images that were entirely abstract. He continued using burlap, which was in surplus in post-war Italy, and also incorporated whatever other materials, mediums and tools were cheap and readily available. His palette and his images resembled the torn apart landscape of his home country and the texture and appearance of so much that had been wasted.

Alberto Burri - Bianco, oil, fabric collage, sand, glue and burlap on canvas, 1952. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Alberto Burri - Bianco, oil, fabric collage, sand, glue and burlap on canvas, 1952. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

The Rush to Meaning

The fact that Burri’s newly abstracted style incorporated colors, textures, materials and forms reminiscent of destruction and carnage seems like an invitation to viewers to assume he was making work about his experiences as a doctor and a soldier. But Burri asserted throughout his career that there was no such meaning to be found in his choices, and that there was no meaning at all in his images. In 1994, he said in reference to his entire oeuvre, “Form and Space! The end. There is nothing else.”

Perhaps in that statement lays the deeper truth Burri discovered about meaning and existence. The only universality shared by all things, including humans and paintings and animals and bombs, is that everything is just matter taking different forms in space. In philosophy, Material Realism prioritizes the physical world over the conscious world. Sometimes atheists use the term in reference to their denial of a spiritual realm. Sometimes scientists use it to separate objective observations from their personal reactions to those same observations. If we are to believe what Alberto Burri himself says about his work (and why shouldn’t we?), his artwork exemplifies Material Realism. It explores the reality of the formal, physical properties of his materials, and nothing more.

Alberto Burri - Sacco e Rosso, acrylic paint and jute sack on canvas, 1954 (Left) / Sacco 5 P, fabric on canvas, burlap and hand stitching, 1953 (Right). © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Alberto Burri - Sacco e Rosso, acrylic paint and jute sack on canvas, 1954 (Left) / Sacco 5 P, fabric on canvas, burlap and hand stitching, 1953 (Right). © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Burri’s Material Realities

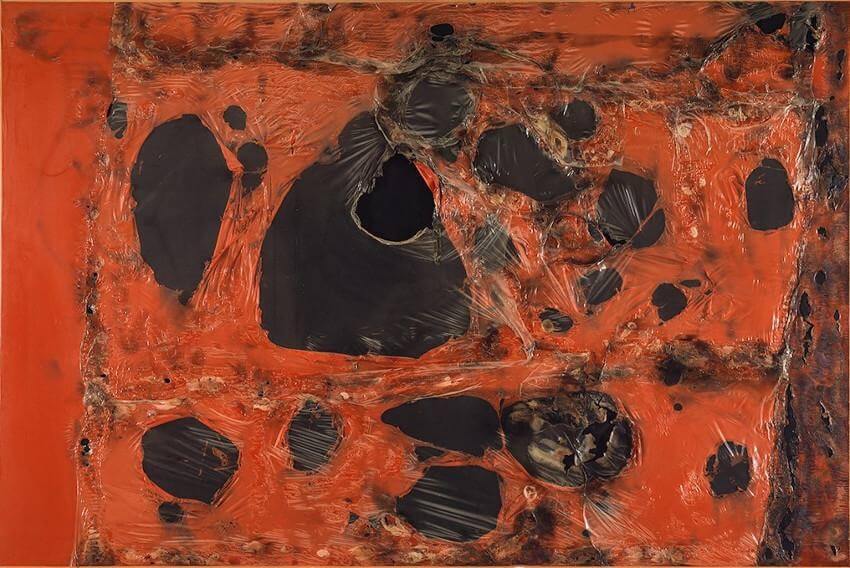

In terms of the formal qualities of his oeuvre, Burri was a wildly creative innovator. He pioneered a range of techniques to create his work, and incorporated an equally diverse range of materials to highlight the impact of those techniques. Borrowing the concept of collage, his images took on a layered appearance that blurred the line between painting, relief and sculpture. His earliest works were mixtures of paint and layered fabric, which he stitched and sewed together. Later he added dimensionality by cutting, slashing and poking holes in his surfaces. He used fire to burn wooden elements of his work, using the charring process to create his forms. He used heat to melt plastic, adding oddly organic dimension and texture to his compositions.

Alberto Burri - Rosso plastica M 2, 1962. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Alberto Burri - Rosso plastica M 2, 1962. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

In an effort to reiterate the formalist nature of his artwork, rather than giving his work poetic names he simply titled them according to their physical nature, using the Italian words for their color, material or the technique he used to make them. His works made with tar he called Catrami, his melted plastic works were Plastichi, his works in wood were called Legni. He called his burlap works Sacchi, the Italian word for bags. The works he made with fire were called Cumbustiono, and his iconic bulging works, which he made by inserting foreign obtrusions behind the surfaces; he named Gobbi, the Italian word for hunchbacks.

Alberto Burri - Rosso Gobbo, 1953. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Alberto Burri - Rosso Gobbo, 1953. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

The Big Crack

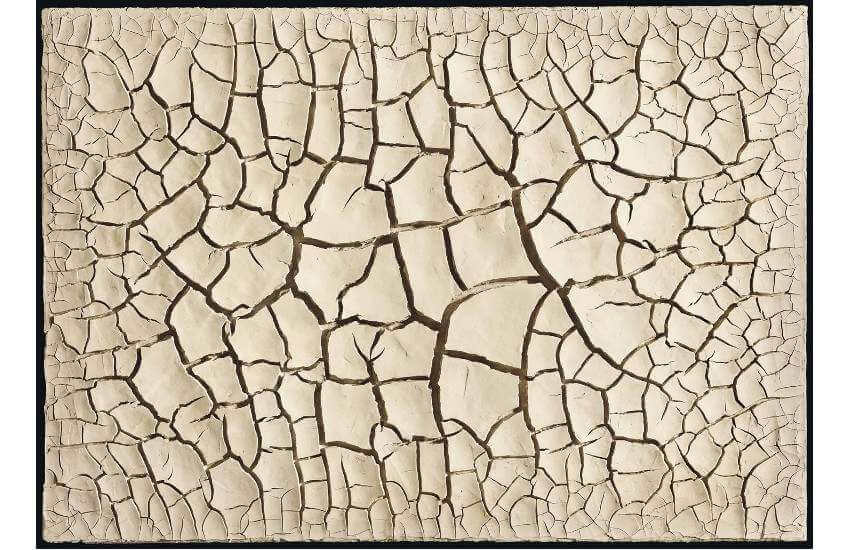

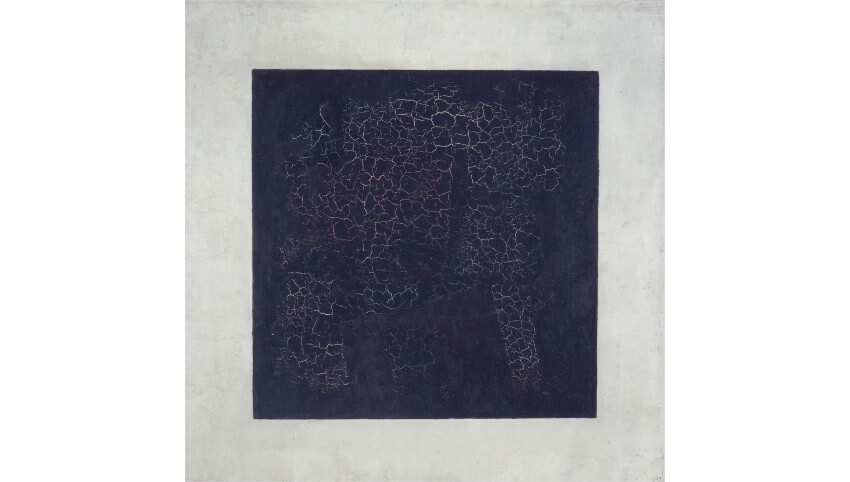

One of the most iconic achievements of Burri’s career came in the form of an aesthetic he pioneered that he called Cretto, a Tuscan slang word for crack. To achieve Cretto, he exaggerated the processes that led to the natural appearance of fine, hairline cracks in various painting mediums as they aged over time, an effect known as called craquelure. The effect is normally considered to be a detrimental thing to a painting. For example, Kazimir Malevich’s seminal painting Black Square, which was once a solid black form, now has aged so poorly that it appears similar to one of Burri’s Cretto paintings.

Alberto Burri - Cretto, Acrovinyl on cellotex, 1975. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Alberto Burri - Cretto, Acrovinyl on cellotex, 1975. © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini Collezione Burri, Città di Castello/2018 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome

Through the appropriation of a process normally attributed to decay, turning it instead into a process of creation, Burri again expresses an essential dichotomy about the meaning of things. He creates through the act of destruction. He finds beauty in decay. The ultimate manifestation of this expression came in 1985 when Burri used it to create his most monumental work, Il Grande Cretto. One of the largest known works of land art, Il Grande Cretto was built over the former site of an annihilated town, the town of Gibellina in Sicily, which was destroyed in an earthquake in 1968. Il Grande Cretto sits above its ruins, a massive assemblage of stone forms and crevices measuring approximately 120,000 square meters.

Kazimir Malevich - Black Square, 1915, 80 cm x 80 cm, © State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Kazimir Malevich - Black Square, 1915, 80 cm x 80 cm, © State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

A Legacy of Innovation

Burri wasn’t the only artist inspired to turn to this kind of an aesthetic after World War II. By the 1960s, so many artists were using discarded, seemingly worthless materials in their work the term Arte Povera, or poor art, was coined to refer to their style. And the term Art Informel was coined to refer to the wild, expressive canvases painters were making through intuition and emotive action. Although Burri’s aesthetic has caused him to be associated with both Arte Povera and Art Informel, he have had a much different reason for embracing this aesthetic than did the others who came in his wake.

Arte Povera was a reaction to something else happening in art; it was a return to a proletarian aesthetic. Arte Informel was an embrace of personal expression and the power of making work that was expressive of something deep and hidden within the work. What Burri did was not a reaction against something else. And no meaning was hidden in his work. He said, “The words don’t mean anything to me; they talk around the picture. What I have to express appears in the picture.” This unique, confident approach to a completely formal examination of materials, form and space left an example that stated something hopeful: Paintings are just paintings. It’s the artist that determines their meaning, and therefore the artist – the living, breathing, creative individual—that should be valued.

Featured image: Alberto Burri - Ferro, 1954, photo credits Guggenheim Museum

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio