Is Art Brut Essentially Abstract or Rather a Figurative Movement?

Before we begin, we have to admit that analyzing whether Art Brut should be read as figurative or abstract is a bit of a folly. By definition, Art Brut designates art that exists beyond the scope of outside analyses. Jean Dubuffet, who coined the term, described Art Brut as art that is, “completely pure, raw, reinvented in all its phases by its author, based solely on his own impulses. Art, therefore, in which is manifested the sole function of invention.” Dubuffet first described Art Brut in a letter to his friend, the artist René Auberjonois, in the 1940s. The description compared raw art to raw gold, which he said he liked “better as a nugget than as a watchcase.” Dubuffet had become intrigued by raw art while reading the book Artistry of the Mentally Ill, published in 1922 by the German psychiatrist Hans Prinzhorn. The book contains the first serious aesthetic analyses of artwork created by institutionalized psychiatric patients. Dubuffet noted the spirit with which these untrained, unknown creators approached their art, which ignored all formal, social and academic conventions. Their art was neither intended for the marketplace nor for critique nor interpretation. It was not made to be questioned; nor necessarily even to be looked at. The artists created it, as Dubuffet said, “for their own use and enchantment.” Nonetheless, we will engage in our folly and analyze Art Brut anyway, because whatever the intent of the artists we believe their creations might hold some meaning for us, and we want to understand them better if we can.

The Uncanny Mind

Who can define the boundaries of mental illness? Sometimes our brains guide us one way, and our instincts another. Sometimes both are absurd. Other times both seem valid. Prior to becoming famous as the doctor who initiated the serious study of art made by people considered to be mentally ill, Hans Prinzhorn was told by his brain to leave Germany and study art history in Vienna. His instincts then told him to move to England to become a professional singer. But before he could achieve his dream, World War I, a sort of global foray into questions of sanity, called him back to Germany, where he was made a surgeon in the war.

The war ended eleven years after Prinzhorn finished his doctorate in art history. Seeing no future in his earlier passions, and having seemingly been misled by both his heart and his brain, he remained in post-war Germany and took a job as an assistant in a psychiatric hospital. And that is when his original instinct to study art history, however seemingly delusional at the time, ended up serving him. His assignment at the hospital was to take responsibility of a large collection of art made by psychiatric patients, assembled by the controversial psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin, a leading proponent of eugenics. Given the task of expanding the collection, Prinzhorn became inspired to write a book detailing the artwork of ten specific psychiatric patients, whom he dubbed the schizophrenic masters.

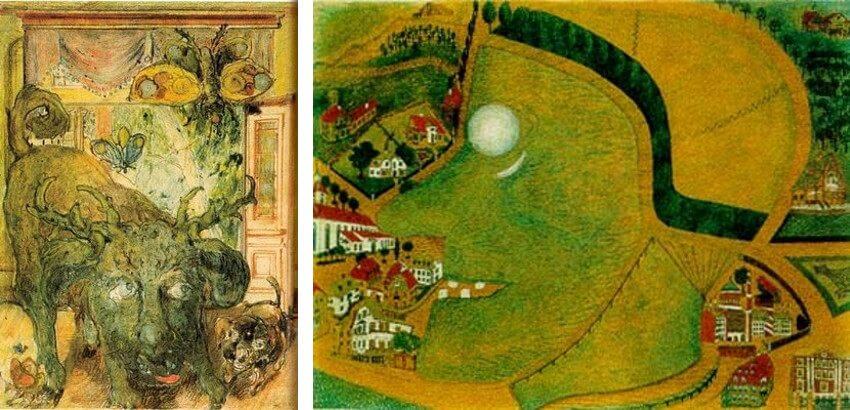

Franz Pohl - L'Horizon Ovipare (Left) / August Natterer - Hexenkopf (Witch's head), c. 1915, Prinzhorn Collection (Right), two works by so-called schizophrenic masters

Franz Pohl - L'Horizon Ovipare (Left) / August Natterer - Hexenkopf (Witch's head), c. 1915, Prinzhorn Collection (Right), two works by so-called schizophrenic masters

The Art Brut Impulse

What Jean Dubuffet saw in the work of the so-called schizophrenic masters was a sense of anti-culture. We all experience creative impulses, sparks of energy leading to the sudden desire to externally manifest internal sensations. But most of us live in cultures that discourage the following of impulses. And even those of us willing and able to act on our impulses inevitably edit or censor them in order to present them to our culture in a comprehensible way. Dubuffet considered culture to be a hindering force that manipulates creativity to fit predetermined definitions of acceptable art.

He saw that these psychiatric patients were not expected to observe the same cultural expectations as the general population. They were not anti-culture in the sense that they were opposed to the culture. They were anti-culture in the sense that they had no cultural reference point at all. They were free to set their own artistic standards. They pursued their artistic impulses with total individuality, giving authority for aesthetic validity entirely to whatever force they perceived to be inspiring them to create. Sometimes that force was a spirit, a god or a demon, or sometimes it was a complex, fabricated, often magical personal narrative. But whatever it was it was unique, and undetermined by academic, historical or social ideas about art.

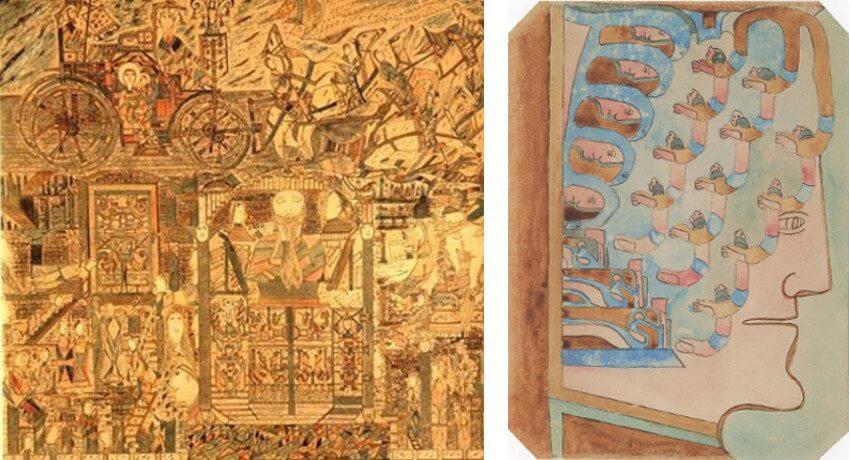

Peter Moog - Destruction of Jerusalem (Left) / August Klett - Wurmlocher (Right), two works by so-called schizophrenic masters

Peter Moog - Destruction of Jerusalem (Left) / August Klett - Wurmlocher (Right), two works by so-called schizophrenic masters

Good Art, Bad Science

Dubuffet said that the creations of these artists came, “from their own depths and not from clichés of classical art or art that is fashionable.” But there was an inherent flaw to that Utopian assumption. Each patients featured in Artistry of the Mentally Ill was previously a productive member of society. They were grown adults, sometimes college educated and often married or divorced, when they were institutionalized. Prior to suffering their illness their own depths had been made filled quite full of cultural expectations, including clichés, fashions, and the many possible reasons for making art. To suppose that they were all free and unhindered in their creative expressions is a leap of the imagination. Perhaps they were. But their true intentions died with them, a secret.

But Dubuffet must have known that. Because when he began collecting examples of Art Brut he did not limit his collection to artwork made by psychiatric patients. He also collected artwork by prisoners, little children, self-taught artists, artists representing primitive cultures, and any other artist he deemed to exist outside of the conventions of the primary, formal artistic culture. He must have realized that the art was good not because it was made by someone who had never known about cultural conventions, but because it was made by someone who had the courage to be idiosyncratic in spite of them. And that is what he eventually tried to achieve in his art, by trying to enter a state of primitiveness while creating his own paintings, hoping to reverse the effects the culture had on his artistic development so that he could return to his own original state of Art Brut.

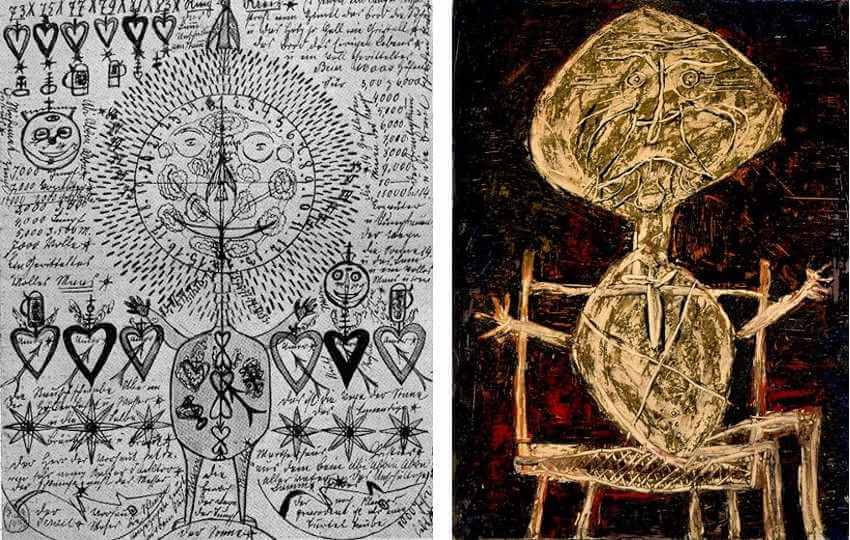

Johann Knopf - Lamm Gottes (Lamb of God), Johann Knopf was one of the artists included in Artistry of the Mentally Ill, (Left) / Jean Dubuffet - Paul Léautaud in a Caned Chair, 1946. Oil with sand on canvas. 51 1/4 x 38 1/8 in. New Orleans Museum of Art. © 2019 ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London (Right).

Johann Knopf - Lamm Gottes (Lamb of God), Johann Knopf was one of the artists included in Artistry of the Mentally Ill, (Left) / Jean Dubuffet - Paul Léautaud in a Caned Chair, 1946. Oil with sand on canvas. 51 1/4 x 38 1/8 in. New Orleans Museum of Art. © 2019 ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London (Right).

A Wider Scope

As to the question of whether Art Brut should be read as abstract or figurative, it seems like that might depend on which Art Brut you mean. Art Brut, like all art, is capable of being both abstract and figurative, perhaps simultaneously so. But in the case of most of the patients featured in Artistry of the Mentally Ill, they often claimed to be reporting specific visions they received in their hallucinations. In other cases they wrote lengthy tomes describing elaborate stories of their imagined life, and the pictures they made were illustrations of those stories. In those cases their work should be considered figurative. It was an illustration of their world, as they realistically perceived it.

But in the case of the Art Brut made by Jean Dubuffet and other artists who followed his lead, we would have to say that there is something fundamentally abstract about it. Regardless of the apparent subject matter, this art emerges straight out of a world of ideas. There are the unknowable ideas that inspired the artist during the act of creation, and there are the ideas that the viewer may extrapolate while interpreting what the artist proposed. But then there is also the overarching idea that it is possible to override the effects of culture, and that what we are looking is the result of the efforts an artist made to accomplish that noble feat.

Featured image: Jean Dubuffet - The Cow with the Subtle Nose, 1954. Oil and enamel on canvas. 35 x 45 3/4" (88.9 x 116.1 cm). Benjamin Scharps and David Scharps Fund. 288.1956. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio