Impasto Painting in Abstract Art

Perhaps the most symbolic building in America is One World Trade Center in Lower Manhattan. As the centerpiece of the development that replaced the twin towers that were destroyed in 2001, its very existence is a powerful statement. Adding prominently to its symbolism are two massive, abstract impasto paintings permanently installed in the lobby of its south entrance. The building is nicknamed Freedom Tower, and it is the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere. It rises 1776 feet: a deliberate reference to the year America declared its independence. The fore-mentioned impasto paintings that adorn the south lobby walls are by the American artist Donald Martiny. One of the paintings is named Lenape, and the other is named Unami. The titles reference the pre-Columbian history of New York. The Lenape are the native tribe that originally inhabited the ground on which Freedom Tower was built. Unami is a Lenape dialect. At the top of Freedom Tower is an observation deck called One World Observatory. As far as the eye can see from the observatory, the entire surrounding environment once supported the Lenape culture. So what is being communicated by this building? It was designed to memorialize one of the worst terror attacks in human history. It puts forward the ideas of one world, freedom, independence and trade. It encourages visitors to take the long view. And its most prominent artworks are named for those who were subjugated to build the nation responsible for its creation. What conversation is taking place here? What is the meaning of all this symbolism? Perhaps there is something to be learned from the artworks themselves, and from the abstract qualities impasto painting represents.

Shadow and Light

The term impasto comes from the Italian word for dough. In painting, it references the technique of applying thick layers of medium on a surface in order to provide a textural dimension to an artwork. The 16th Century Italian painter Titian was one of the first artists known to have intentionally incorporated impasto techniques into his paintings. He began using the technique during a time when paintings were prized for their smooth surfaces and lack of visible brushstrokes. A masterful realistic painter, Titian realized that by accumulating paint in certain areas on a surface he could create variations in how light reflected off of it, giving elements of a painting a life-like feel.

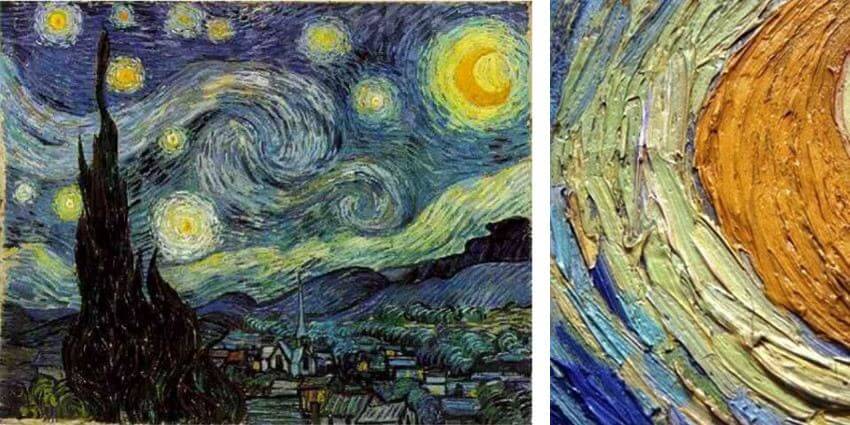

Each impasto painting brushstroke causes gradations in color to appear from the shadows caused when light hits the raised paint. Depending on the position of lights and the point of view of a spectator, an impasto painting can shift in subtle ways, adding variations of depth and a heightened sense of realism. In his own century, Titian was bucking tradition by allowing his brushstrokes to be visible and the material properties of his medium to show. But he was so masterful at the technique that his influence caused it quickly to catch on. In the 17th Century, Rembrandt was famously incorporating impasto painting into his works. And by the 19th Century, the technique was so well regarded that Van Gogh made it his trademark style.

Van Gogh - The Starry Night, 1889, 1889. Oil on canvas. 29 x 36 1/4 in. MoMA Collection. © Van Gogh (Left) and detail (Right)

Van Gogh - The Starry Night, 1889, 1889. Oil on canvas. 29 x 36 1/4 in. MoMA Collection. © Van Gogh (Left) and detail (Right)

Abstract Expressions

Around the turn of the 20th Century, a group of painters called the Expressionists were looking for ways to express inner emotional states in their paintings rather than simply capturing outer reality. They adopted impasto painting as one of their preferred techniques. Thickly layered paint possesses many inherent qualities, such as weight, depth and gravity. The thicker it is applied the more shadow it creates. It abstracts imagery, distorting the way viewers interact with subject matter. The Expressionists found it ideal for communicating seriousness, intensity and drama.

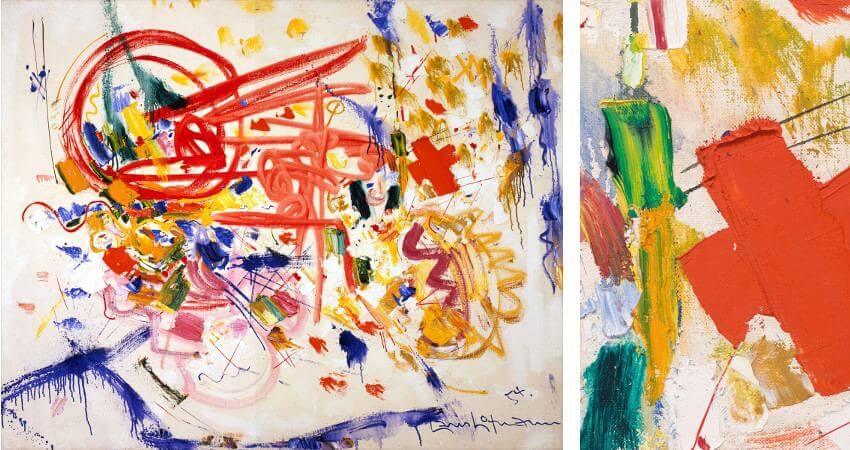

Around the same time as Expressionism was gaining in prominence, abstraction was also becoming a growing concern for many artists. Impasto painting turned out to be an ideal technique for abstract painters since it helped shift the focus of a painting away from subject matter and onto the formal qualities of the work. An abstract impasto painting therefore, does not have to be about anything but the paint. Hans Hofmann was one particularly influential abstract artist who fully embraced impasto painting. Hofmann believed that by focusing on the formal elements of aesthetics rather than mimicking reality, artists could express deeper truths. He used impasto painting to express the abstract qualities of structure, space, color, form and illusion.

Hans Hofmann - Laburnum, 1954. Oil on linen. 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm). Private collection. Courtesy Tom Powel Imaging (Left) and painting detail (Right)

Hans Hofmann - Laburnum, 1954. Oil on linen. 40 x 50 in. (101.6 x 127 cm). Private collection. Courtesy Tom Powel Imaging (Left) and painting detail (Right)

Sculptural Dimensions

In addition to being a painter, Hofmann was also a teacher. Many of the students he taught, such as Helen Frankenthaler and Lee Krasner, the wife of Jackson Pollock, went on to become leading figures in the Abstract Expressionist movement. Hofmann had a profound effect on the way these painters related to their mediums. Since the focus of many Abstract Expressionist painters was to convey their subconscious feelings, and to capture on canvas the emotion and intensity of the act of painting, Hofmann instilled in them that the material qualities of their medium should be a key element in their work.

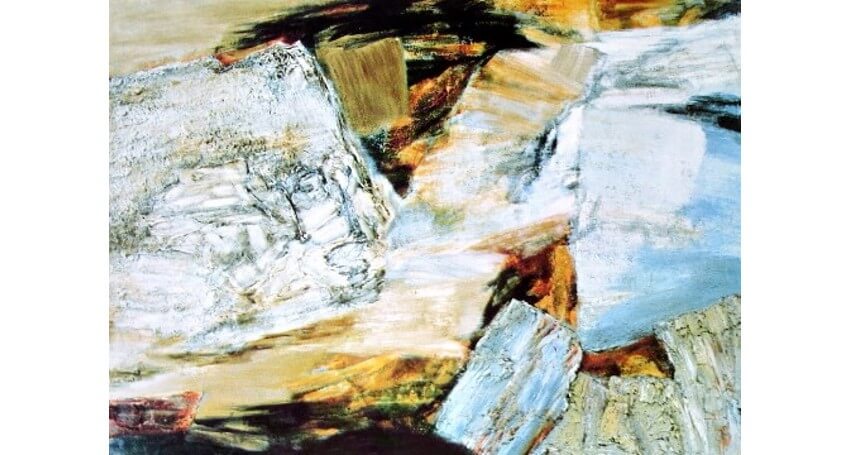

He taught them that, “each medium of expression has its own order of being.” In the hands of painters like Jackson Pollock and Jane Frank, impasto painting took on an entirely new dimension, literally. Jane Frank built sculptural layers of mediums onto her impasto surfaces. Jackson Pollock splattered, dripped and poured paint in such massive amounts that the sheer weight of his impasto layers threatened to destroy the supports of his works. The Abstract Expressionists furthermore expanded the concept of impasto painting to include stuff other than paint, like unusual mediums and detritus such as broken glass, stones, cigarette butts. By adding unusual materials and mediums to their impasto layers these painters expressed conceptual as well as physical depth.

Jane Frank - Crags and Crevices, 1961. Oil and spackle on canvas. 70 x 50 in. © Jane Frank

Jane Frank - Crags and Crevices, 1961. Oil and spackle on canvas. 70 x 50 in. © Jane Frank

All About the Paint

In response to the emotional intensity of Abstract Expressionism, impasto painting fell out of favor with many artists in the 1960s and 70s, especially those associated with Minimalism. These artists sought to create smooth surfaces that eliminated evidence of the individual artist who made the work. To create ultra smooth surfaces they turned to techniques such as staining and spraying, and used mechanized and industrial processes. But by the 1980s the love for impasto returned.

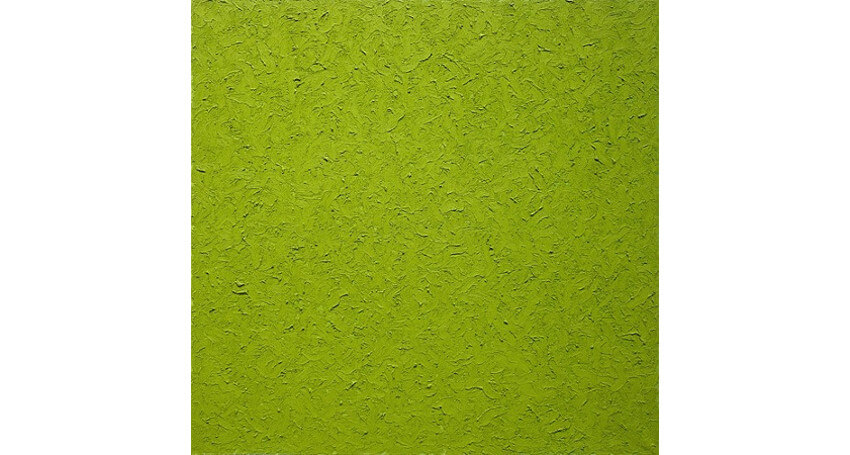

Alan Ebnother - Abide 95-11, 1995. Oil on linen. 28.25 x 28.25 in. 71.76 x 71.76 cm. Courtesy George Lawson Gallery. © Alan Ebnother

Alan Ebnother - Abide 95-11, 1995. Oil on linen. 28.25 x 28.25 in. 71.76 x 71.76 cm. Courtesy George Lawson Gallery. © Alan Ebnother

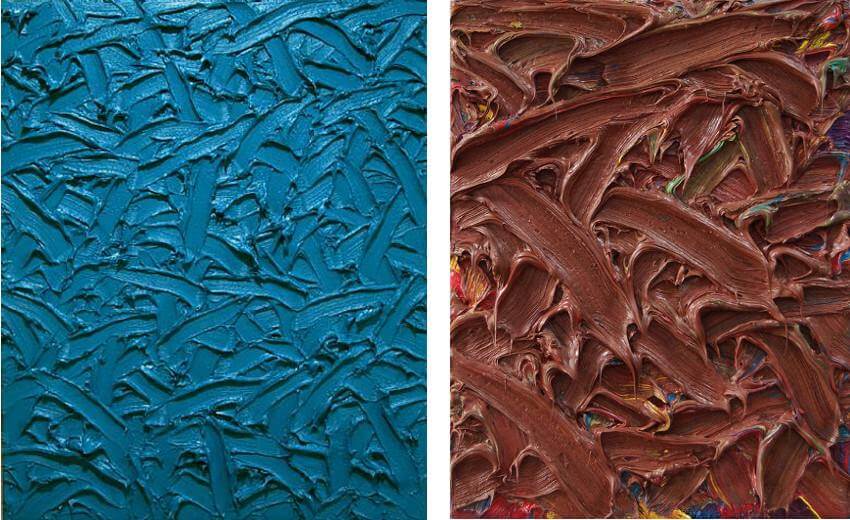

One reason the technique regained its favor was a reaction against the perceived soullessness of Minimalism. Another reason was a growing interest in the formal qualities of artistic materials. One particularly successful expression of the Minimalist aesthetic was the monochrome painting. Monochromes express pure color and flatness. In the 1980s, painters such as James Hayward and Alan Ebnother began re-imagining the monochrome through impasto painting. Their impasto monochromes embraced the expression of color but added a dimension of physicality and medium specificity. By eliminating the industrial anonymity of Minimalist monochromes and reintroducing the mark of the artist they reprioritized emotion and personality, and brought renewed attention to the essential qualities of paint.

James Hayward - Abstract 31, 2001. Oil on canvas on board. 30 x 28 in. © James Hayward (Left) and Asymmetrical Chromachord 38, 2009. Oil on canvas on wood panel. © James Hayward (Right)

James Hayward - Abstract 31, 2001. Oil on canvas on board. 30 x 28 in. © James Hayward (Left) and Asymmetrical Chromachord 38, 2009. Oil on canvas on wood panel. © James Hayward (Right)

Beyond Impasto

Looking back over the history of impasto painting it is clear the technique carries with it a range of abstract associations. In its earliest days, it took the unprecedented step of not hiding the fact that a work of art was made from paint. In that sense, it shattered illusion. It later served to highlight the subtle and often shifting differences between darkness and light. In the Modernist era, impasto painting became a way to express the deep emotion and primal sensibilities of the subconscious mind. And in its contemporary use it has become an expression of the power and simplicity of the artistic gesture itself. So what can we ascertain about the conversation taking place between One World Trade Center and the abstract impasto paintings by Donald Martiny that occupy its lobby?

Though these paintings appear to be massive impasto brushstrokes, they were actually meticulously made in a laborious process, during which Martini pours, drips and smears layer after layer of medium, sometimes using his bare hands. They express hard work, adaptation, patience, vision, and the strength inherent in the careful building up of layers over time. Beyond that, like all impasto paintings Lenape and Unami also symbolize the shattering of illusions, the evolving nature of darkness and light, the range of emotional and physical depth, and the primal realities of the subconscious human mind. Considered from this perspective they become more than aesthetic objects, and more than symbolic gestures. They become the perfect abstract representatives of their medium, their environment, their namesakes, their history and their time.

Featured image: Donald Martiny - Lenape, One World Trade Center, 2015, © Donald Martiny

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio