Vibrancy and Energy in Joan Mitchell Paintings

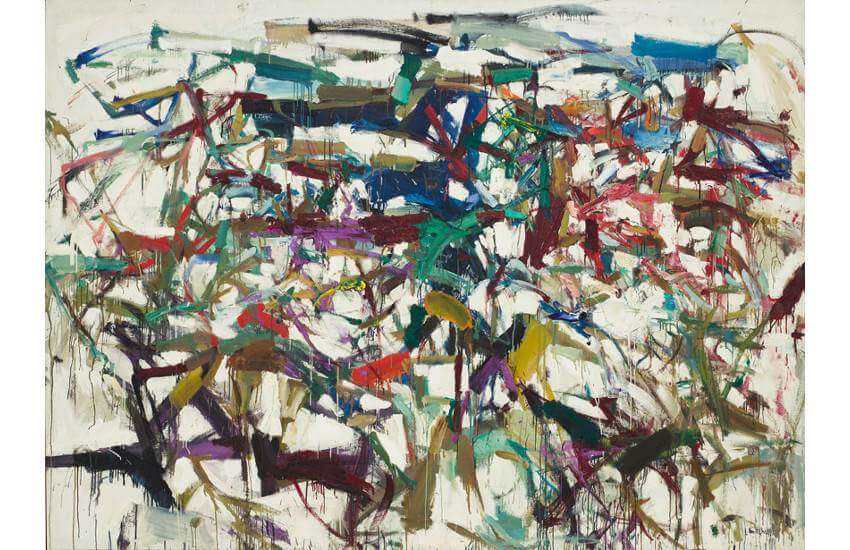

When we look at a Joan Mitchell painting we are looking at an image of liberty. We are looking at abandon made palpable. Mitchell approached the act of painting from a place of total freedom, without a blueprint going in, or a definitive plan. Whatever ended up on the canvas came from her intuition, and was an immediate reflection of her truth. It may be joy that she felt, or anger, or fear; it may be an image formed from bits and pieces of a memory she was holding in her head, or a beloved landscape she was holding in her heart. When we encounter her paintings, in the midst of a quick or casual glance, we may or may not feel what Mitchell felt. We may or may not recognize the exact meaning she hoped to convey. But the energy that flowed through her with every brushstroke screams at us. It arrests us in space and speaks to whatever primal stuff inside of us recognizes it for what it is: the vibrant, timeless, universal echo of love, loss, joy, fear, pride and pain.

Taking Action

Every brushstroke made by a painter is the result of physical motion. Yet not every brushstroke manages to announce that motion to viewers. Some brushstrokes intentionally seek to hide the motion that created them, and to ignore that a human hand was involved at all. It is one of the hallmarks of action painters that they are able to convey on the surface of a canvas the power and energy of the movement of their physical body through space. Joan Mitchell was an action painter, a member of what is considered the second generation of Abstract Expressionist artists. But she did not begin her career focused on gesture and movement, or abstraction, or even necessarily painting. While in school at the Art Institute of Chicago she was a talented figurative artist, who had won awards for her lithography.

But Mitchell was always an extremely physical person. In high school in Chicago she was a nationally competitive athlete, placing as high as fourth in the U.S. Figure Skating Championships. A knee injury ended her sports career. But after she graduated from the Art Institute of Chicago in 1947 she moved to New York and was exposed to the work of gestural abstract painters like Arshile Gorky and Jackson Pollock. She immediately incorporated physicality into her painting technique. By 1951 she had developed a mature, abstract gestural style, and had befriended several of the first generation Abstract Expressionists, like Will de Kooning and Franz Kline, and by invitation had even joined their prestigious Eighth Street Club, which hosted artist get-togethers and talks.

Joan Mitchell - Ladybug, 1957. Oil on canvas. 6' 5 7/8" x 9' (197.9 x 274 cm). The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Collection, New York. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Joan Mitchell - Ladybug, 1957. Oil on canvas. 6' 5 7/8" x 9' (197.9 x 274 cm). The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) Collection, New York. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

The Landscapes of Joan Mitchell

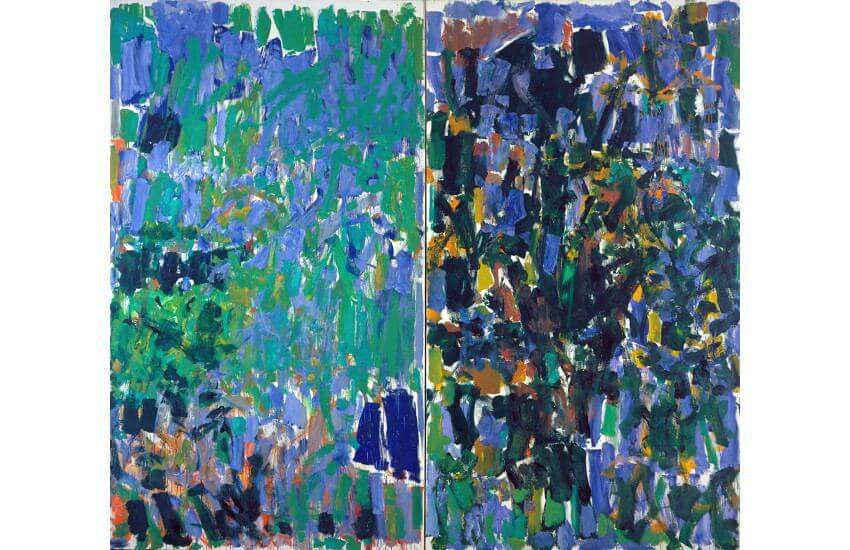

Having grown up just a couple of blocks from the shores of Lake Michigan in Downtown Chicago, Joan Mitchell had, from a young age, developed a profound emotional attachment to the horizon line where the water meets the sky. And as an adult living off and on in the countryside of France, as well as in the Hamptons, she also developed a great love for rural landscapes. Even though her mature works are all considered abstract, she often referred to herself as a painter of landscapes. Many of her paintings had the word landscape in the title, or were named after scenic places that were dear to her heart.

It is possible in many of her paintings to find visual hints of compositions, forms or color palettes that suggest a natural landscape, or even to find faint echoes of horizon lines. But the types of landscapes Mitchell painter were not figurative attempts at capturing the natural world. Rather, Mitchell internalized a sense of the emotions she felt while in certain places that were dear to her. She had a keen aesthetic sensibility and connection to nostalgia, and would strive to capture the color, balance and harmony of her beloved landscapes while also communicating the energy and personal emotion she attached to it in her memory.

Joan Mitchell - Heel, Sit, Stay, 1977, oil on canvas (diptych), Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Joan Mitchell - Heel, Sit, Stay, 1977, oil on canvas (diptych), Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Complementary Opposites

Much of the power we can sense in Joan Mitchell paintings seems to be related to the idea of opposing forces. One prominent example is in the way she shifted away from the so-called all-over painting style, in which the entire canvas is covered with abstract imagery, to a more traditional figure-ground compositional approach, featuring large areas of white or unprimed canvas. But rather than seeing opposing forces at work in her figure and ground compositions, it is more accurate to say the forces are complementary. They do not object to each other or resist each other. The figure and ground shift roles, elucidating one another and trading influence over the gaze of the viewer.

Likewise, the other apparent opposites visible in her works function the same way. Light brush marks complement aggressive brush marks, defining each other with their relative differences; dense, layered, impasto surfaces lend presence to their flat counterparts; geometric or biomorphic forms are exalted by lyrical abstract markings. The unifying essence running throughout the oeuvre of Joan Mitchell is not one of opposition, but one of engagement to a world of complementary relationships building to a harmonious whole.

Joan Mitchell - Edrita Fried, 1981. Oil on canvas. Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Joan Mitchell - Edrita Fried, 1981. Oil on canvas. Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Abstraction Inchoate

Over the course of her career, Joan Mitchell changed her aesthetic several times. Each change was connected to either a geographical shift or a change in personal circumstances. One of the biggest periods of change she experienced was in the 1960s, when she lost both of her parents and a dear friend in just a few years. Another came in the 1980s when she was diagnosed with cancer. Whereas each aesthetic change seems expressive of different distinct emotional nuances, none feel like an end to something. Each evolution in her work possesses a sense of the inchoate; the embryonic promise of something new and as yet unformed.

After the decade of losses she experienced in the 1960s, Mitchell shifted toward geometric figuration, and then soon shifted again, back toward all-over painting. Her palette changed to deep greens and vibrant yellows, reflecting the colors of nature. Then in the 1980s her palette changed to include more pure and primary colors: blues, oranges, greens and reds. Her brushstrokes became short and stout, electrified, and almost vibrational. Each new phase communicates the idea of a new, undetermined beginning, and is thus inherently communicative of something hopeful and new.

Joan Mitchell - Trees, 1990-91. Oil on canvas. Private collection. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Joan Mitchell - Trees, 1990-91. Oil on canvas. Private collection. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

Letting Go

Throughout all of the stages of her oeuvre an enduring sense of energy and vibrancy is present in the paintings of Joan Mitchell, whether through her brushstrokes, her compositions, her harmonies or her use of complementary opposites. That energy continues to inspire the third generation of Abstract Expressionist painters working today, like Francine Tint. It also informs the work of contemporary gestural abstractionists like Ellen Priest.

A universe of emotions opens up in the work of these painters, always fluctuating between the darkest energy and the lightest, the most aggressive and the most serene, jumping off the surfaces of their paintings with a frantic sense of immediacy. Mitchell once described the source of that frantic immediacy by likening the way she felt when painting to an orgasm. She also once described it as “riding a bike with no hands.” Both descriptions speak to the utter joy of emotional release possible with an act of total abandon. And both speak to the expression of human honesty only possible when someone is free.

Featured image: Joan Mitchell - Untitled, 1977, oil on canvas, Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York. © Estate of Joan Mitchell

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio