Jean-Paul Riopelle and the Expression Between Layers of Color

Each nation, like each person, possesses a unique character. Nations express their character through culture, and culture is influenced by art. By challenging how people perceive of their societies and themselves, artists can affect culture, and by extension alter the character of their nations. In the 1940s, Jean-Paul Riopelle joined a group of artists dedicated to the idea that they could radically change the culture and character of Canada. In a sense, they were the first generation of truly Canadian artists, since it was only in the 1930s that Canada gained legislative independence from the United Kingdom. Dissatisfied with what they perceived as the emergence of a stagnant, backwards-looking Canadian culture, these artists published a manifesto titled La Refus Global (Total Refusal). It spelled out their secular, liberal, experimental vision for the future of Canadian art and society. “Make way for magic!” the manifesto announced. “Make way for objective mysteries! Make way for love! Make way for necessities!” Although it quickly became clear that Canada was not ready for radical change at the time, the signers of La Refus Global nonetheless went on to profoundly affect Canadian culture. And its most prominent signer, Jean-Paul Riopelle, created an oeuvre that today embodies the diverse, liberal, experimental character of the nation Canada has become.

Made in Montreal

The island on which the city of Montreal is built possesses a sacred and ancient stature. Humans have occupied it for roughly 4,000 years. The First Nations recognize it as the First Stopping Place, the prophetic primary destination for the Anishinaabe people along their journey in the Seven Fires Prophecy. The word Anishinaabe translates into Spontaneous Beings, or Beings Made Out of Nothing. The contemporary motto of Montreal is Concordia Salus, or Wellbeing Through Harmony. Spontaneity, creation, harmony; what better sentiments for the epicenter of modern Canadian abstract art?

Jean-Paul Riopelle was born in Montreal in 1923. He began art classes at age 10, and in college studied at l'École du Meuble under the renowned founder of the Automatiste movement Paul-Émile Borduas, chief author of La Refus Global. After graduating, inspired by his professor and the writings of the Surrealist André Breton, Riopelle embraced a purely abstract painting style. But Canadians were less than enthusiastic toward his work. Even poor Borduas was fired from l'École du Meuble for the statements he made in La Refus Global. Luckily elsewhere the mood was better for experimental artists. So in 1947, Riopelle left his beloved Canada and moved to Paris.

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Hochelaga, 1947. Oil on canvas. © 2019 Estate of Jean-Paul Riopelle / ARS, NY

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Hochelaga, 1947. Oil on canvas. © 2019 Estate of Jean-Paul Riopelle / ARS, NY

Jean-Paul Riopelle and Lyrical Abstraction

In Europe, Riopelle immediately became immersed in the ideas surrounding Lyrical Abstraction, an aesthetic position roughly equivalent to Abstract Expressionism in the US. He combined its active gestures and expressionistic freedoms with the intuitive approach to composition he had been developing. He worked instinctively and fast, exploring a range of mediums and techniques to express fundamental elements like volume, line, color and value.

Sometimes he worked in watercolor and ink on paper. Other times he squirted paint directly from tubes in heaps onto a canvas then scraped it across the surface with knives or spatulas. The effect Riopelle created was both explosive and unique. Not content however to stick with just painting, by the mid-1950s he ventured into printmaking and sculpture. In fact, one of his most famous works is a kinetic sculpture fountain in Montreal called La Joute. Composed of cast bronze abstractions of people and animals, La Joute repeats a timed series of mater, mist and fire elements twice each hour.

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Composition, Oil on canvas, 1954. © 2019 Estate of Jean-Paul Riopelle / ARS, NY

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Composition, Oil on canvas, 1954. © 2019 Estate of Jean-Paul Riopelle / ARS, NY

Jean-Paul Riopelle and Joan Mitchell

Around 1959, Riopelle began a romantic relationship with the American Abstract Expressionist painter Joan Mitchell. The two maintained separate residences and studios in France but got together nightly to imbibe. The work Riopelle started making around this time began shifting more toward figuration. Not that his paintings were objective, but his use of color and what Hans Hofmann called push and pull started to result in images in which a more defined sense of figure and ground emerged.

By the late 1970s, his relationship with Mitchell had ended and Riopelle moved back to Canada. But rather than moving to the city he moved to an environment dominated by snow, ice and rock. The visual aspects of his surroundings contributed even more to his transition toward figuration. He painted abstract responses to his environment that could be read as landscapes, and also began incorporating primitive imagery into his works, inspired by native Canadian culture.

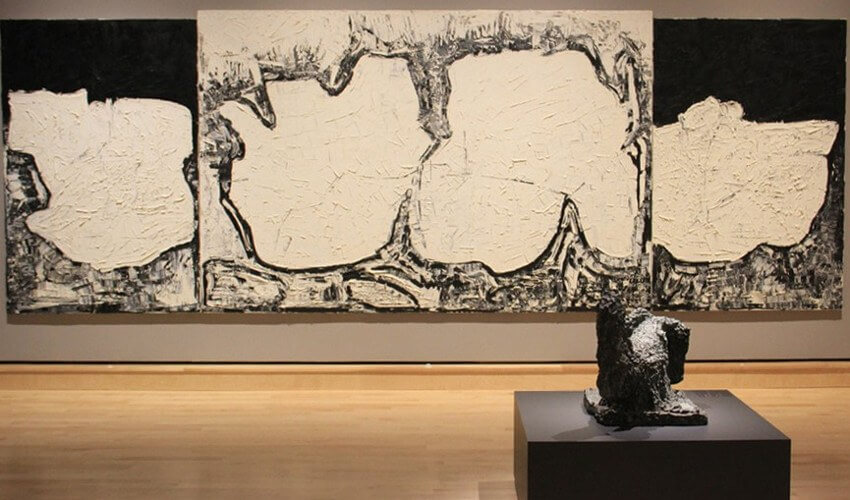

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Pangnirtung, 1977. Oil on canvas. Triptych. 200 x 560 cm. (3 canvases). with Riopelle sculpture in foreground

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Pangnirtung, 1977. Oil on canvas. Triptych. 200 x 560 cm. (3 canvases). with Riopelle sculpture in foreground

Experiments in Volume and Color

When Mitchell died in 1992, Riopelle created what many consider his masterpiece, a monumental spray paint work created in her honor called Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg. The work represents the evolution of his skill as a painter. It speaks to his ability to create volume in space, his mastery of color and his ability to harness the stark emotive power of black and white. But most telling is its flatness. Often noted for his impasto technique, Riopelle once commented that he considered that to be a reflection of his amateurishness, saying, “When I begin a painting, I always hope to complete it in a few strokes…I have never wanted to paint thickly; paint tubes are much too expensive. But one way or another, the painting has to be done. When I learn how to paint better, I will paint less thickly.”

But even in his impasto works, somewhere between those unintentional layers a search for something is revealed. In each of his pieces Riopelle expresses an intuitive journey into the unknown. What he expressed between his layers of paint offers one of the most compelling glimpses of what it means to be a Canadian abstract artist. With his luminous language of color and volume he created something distinctly new, while remaining true to the ancient, sacred spontaneity and harmony of his home.

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg (detail), 1992. Acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 155 x 1 424 cm (1st element); 155 x 1 247 cm (2nd element); 155 x 1 368 cm (3rd element), Collection MNBAQ (The Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec). Gift of the artist. © 2019 Estate of Jean-Paul Riopelle / ARS, NY

Jean-Paul Riopelle - Tribute to Rosa Luxemburg (detail), 1992. Acrylic and spray paint on canvas, 155 x 1 424 cm (1st element); 155 x 1 247 cm (2nd element); 155 x 1 368 cm (3rd element), Collection MNBAQ (The Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec). Gift of the artist. © 2019 Estate of Jean-Paul Riopelle / ARS, NY

Featured image: Jean-Paul Riopelle - Hommage à Robert le Diabolique (detail), 1953. © 2019 Estate of Jean-Paul Riopelle / ARS, NY

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio