Helen Frankenthaler

Helen Frankenthaler was an immeasurably influential American abstract artist known for, among other things, kick-starting Post-Painterly Abstraction. She championed individuality and experimentation. Through her innovative techniques and intellectual demeanor she pioneered methods of painting that defined not only her career, but also those of several of her contemporaries. Over the course of a professional career that spanned six decades Frankenthaler remained dedicated to openness and originality, demonstrating the value of her personal motto: “There are no rules. That is how art is born, how breakthroughs happen. Go against the rules or ignore the rules. That is what invention is about.”

The World in Her Arms

Although she is considered a master of abstraction today, Helen Frankenthaler once described her early development toward abstraction as difficult. She studied Cubism and Neo-Pl/blogs/magazine/what-is-cubism-a-true-art-revolutionasticism in school, but only responded to their ideas on an intellectual level. They did not inspire her to make abstract work of her own. It was not until after college, after meeting some forward-thinking working artists and theorists, that Helen was able to discover her unique abstract voice.

The most influential connection Frankenthaler made after leaving college was the art critic Clement Greenberg, whom she met at an art exhibition in 1950. Greenberg encouraged her to take classes from the painter and educator Hans Hofmann and also introduced her to the Abstract Expressionist painters Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. In the methods of Hofmann, Pollock and Krasner, Frankenthaler saw a path toward innovation. She was particularly moved by how Jackson Pollock laid his canvasses on the floor and poured paint directly onto them. She quickly adopted that method. After a trip to Nova Scotia, saying that she then held the beautiful landscapes of that place in her arms, Frankenthaler laid an unstretched swath of canvas on the floor of her studio and commenced to communicate their essence in a painting called Mountains and Sea.

Helen Frankenthaler - Mountains and Sea, 1952. Oil and charcoal on unprimed canvas. 86 3/8 × 117 1/4 in. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Helen Frankenthaler - Mountains and Sea, 1952. Oil and charcoal on unprimed canvas. 86 3/8 × 117 1/4 in. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

A Leap Forward

Mountains and Sea was a groundbreaking painting. What made it groundbreaking were two key differences Helen Frankenthaler innovated that distinguished her technique from what Pollock was doing. Rather than using the thick enamel paint Jackson Pollock used, Frankenthaler used oil paint thinned down with turpentine. And rather than priming her canvas first, she left it completely raw. The effect the thinned out paint had on the unprimed canvas was that rather than accumulating atop the surface, the paint soaked directly into it, staining it.

Frankenthaler called this the soak-stain method, and it was something new. Always before, paintings had consisted of two elements: the surface, and the image that was painted atop it. With her spontaneously invented soak-stain technique, Frankenthaler merged the surface with the image, creating a unified aesthetic object. The field became one with the color. She insisted that the impetus to paint in such a way was simply to create a beautiful picture, and that she had not intended to revolutionize painting. But as a serious student of art history, she understood precisely the implications of her discovery.

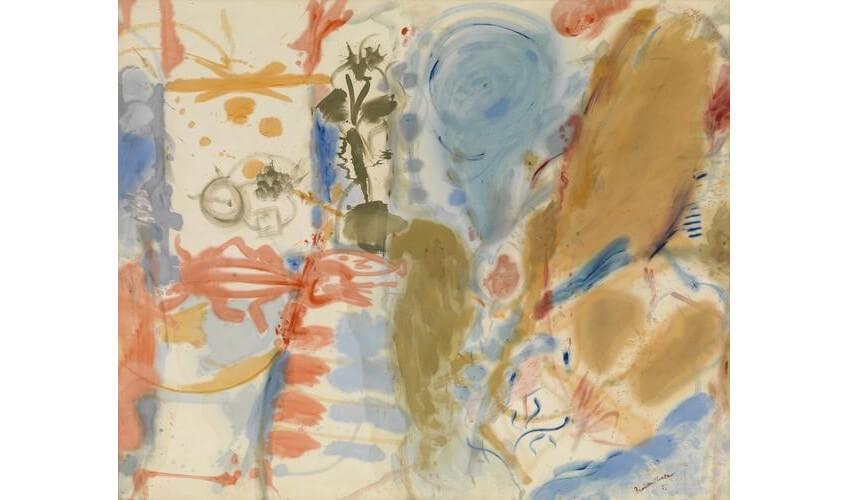

Helen Frankenthaler - Grotto Azura, 1963. Oil on paper. 23 x 29 in. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Helen Frankenthaler - Grotto Azura, 1963. Oil on paper. 23 x 29 in. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Next Big Thing

Frankenthaler showed Mountains and Sea to Clement Greenberg. He in turn invited the painters Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland up from Washington, D.C., for a studio visit with Frankenthaler, to show them her discovery. Noland and Louis had each been searching for methods of exploring color relationships without the object-ness of the painting and the personality of the artist interfering. The soak-stain technique was what they had seeking. It eliminated brushstrokes and flattened the painting, allowing image and object to become one, putting all of the focus on color and field.

Louis and Noland returned to Washington, D.C., and immediately began employing this new technique. Clement Greenberg meanwhile publicized this trend as something distinctly different from the emotionally charged, painterly works of the Abstract Expressionists. To describe what Frankenthaler had discovered, and what many other painters were subsequently appropriating, Greenberg coined the term Post-Painterly Abstraction, calling it the next big thing in American art.

Helen Frankenthaler - Western Dream, 1957. Oil on unprimed canvas. 70 x 86 in. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Helen Frankenthaler - Western Dream, 1957. Oil on unprimed canvas. 70 x 86 in. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Transcendence

Over the next two decades, Frankenthaler flourished into an influential and renowned artist. In 1960, at age 32, she enjoyed a retrospective at the Jewish Museum in New York. Nine years later she had a retrospective at the Whitney Museum and major exhibitions throughout Europe. Along with Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Mark Rothko, Clifford Still, Jules Olitski and many others, she became known as a founder and leader of the Color Field movement, a broad, multifaceted exploration of color and its potentially transcendent qualities.

Then in the early 1970s, at the height of her success, Helen Frankenthaler made an experimental choice that led to her second major artistic breakthrough. She took up woodcut printing. She had been making other types of prints and works on paper since the 1950s, but woodcut printing presented specific challenges. Woodcut prints had a particular aesthetic defined by white lines and hard edges. She wanted to eliminate the lines and hard edges in order to simulate the same ethereal fields of color she coaxed from her soak-stain process. She achieved that goal in 1973, with a woodcut print titled East and Beyond. The print possessed the rustic beauty of a woodcut, but its delicate, organic-looking, uninterrupted fields of color set it apart from any woodcut print ever made. The process she invented revolutionized the medium just as her soak-stain technique had done to painting decades earlier.

Helen Frankenthaler - East and Beyond, 1973. 8 color woodcut on buff laminated Nepalese handmade paper. 31 ½ x 21 ½ in. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Helen Frankenthaler - East and Beyond, 1973. 8 color woodcut on buff laminated Nepalese handmade paper. 31 ½ x 21 ½ in. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Beyond Art

In addition to her artworks, Helen Frankenthaler created and funded a foundation that continues today to encourage artistic innovation through grants, exhibitions and other projects. She also participated as an advisor to the National Endowment for the Arts in the 1980s. Infamously, her recommendations in that role led to the budget of that organization being reduced. Explaining her intentions, she said, “I feel there was a time when I experienced loftier minds, relatively unloaded with politics, fashion, and chic. They encouraged the endurance of a great tradition and protected important development in the arts.”

Though controversial, Helen Frankenthaler hoped her work for the NEA would raise the level of intellectual discourse among artists, and encourage a higher level of work. It was precisely her own dedication to research, education, openness, originality, and smart experimentation that led to the innovative work that defines her oeuvre. That was also what allowed her, by the time she passed away at age 83, to make an indelible mark on the history of 20th Century abstract art, and to serve as an example to future artists as they look for a direction in which to strive.

Featured image: Helen Frankenthaler - Grey Fireworks (detail), 1982. Acrylic on canvas. 72 x 118 1/2 in. © 2019 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio