The Politically Abstract Art of Dia al-Azzawi

Jul 28, 2017

Iraqi-born artist Dia al-Azzawi is no stranger to conflict. He has spent a lifetime in the crosshairs: sometimes literally, as when he was forced by Ba’ath extremists that had taken control of the Iraqi government to fight his own neighbors in the 1960s. Describing that tragic period, al-Azzawi once recalled, “It felt like I was fighting my friends.” But more often, al-Azzawi has found himself in the metaphorical crosshairs of social, cultural and political battles, as an artist determined to take sides in the multitude of contentious debates that are shaping the present and future of his beloved Middle East. The latest manifestation of al-Azzawi bringing art to a culture fight is unfolding right now in the Middle Eastern city of Doha. In the scenic, waterside MIA Park (named for the neighboring Museum of Islamic Art, which opened in 2008), al-Azzawi recently unveiled his latest public sculpture, titled Hanging Garden of Babylon. According to al-Azzawi, the work is a reference to the ancient and ongoing human tendency toward self-destruction. The location and timing of the piece is appropriate. Doha is the capital city of the nation of Qatar, which has been in the news in recent weeks as the target of a conglomerate of United Arab Emirate powers that has blacklisted it for its alleged support of terror organizations. As a cultural and political refugee himself, one who has watched from afar as his native land has been systematically destroyed by a coalition of international influences, al-Azzawi is all too familiar with the fact that in war, all sides commit atrocities. With this timely sculpture he points out that we need not go back all that far to find a time when we were all part of the same human family, and that the definition of terrorism often depends on which side of the fight one is on. It is just the latest such declaration by an artist who has spent his entire life engaged in the revolutionary act of reminding his fellow world citizens of the ancient, and potentially enduring, heritage to which we all belong.

Art Saves

It would be no exaggeration to say that Dia al-Azzawi owes his life to art. In an interview al-Azzawi gave to Saphora Smith for the Telegraph newspaper back in 2016, he revealed the unlikely story of how art quite literally saved him from what easily could have been a life of obscurity, disillusionment, and perhaps worse. Born in 1939 in Baghdad, al-Azzawi was a socially and culturally engaged teenager at a time of political awakening across the Middle East. It was an era of burgeoning industrialization throughout the region, when the major powers of the world were actively engaged in attempts to push their influence whenever and wherever they saw fit. One of the biggest events to shape how the modern day Middle East evolved also had a profound affect on the evolution of the young Dia al-Azzawi. The story begins in the early 1950s, when Egypt, fresh from the revolution of 1952, committed itself to constructing the Aswan Dam across the Nile river, a project Egyptians hoped would aid significantly in the economic growth of the country.

After various Western nations withdrew their support for the Aswan Dam project, Egyptian President Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, vowing to raise money for the dam by charging tolls on what was formerly an internationally open shipping channel through Egypt providing direct passage between the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. Simultaneously, Nasser also banned Israeli ships from another important shipping channel, the Straits of Tiran. In response, Western nations conspired with Israel to invade Egypt and topple the Nasser regime. Across the Middle East, and really the entire world, people took sides. When what is now called the Suez Crisis reached its apex in 1956, Dia al-Azzawi was 17 years old. He and his friends joined the protests and were arrested for throwing rocks at the Iraqi police. He was subsequently kicked out of school. But as fate would have it, only a couple of weeks later the Iraqi King, Faisal II, a major art supporter, was scheduled to visit the school. Because of his artistic talent, al-Azzawi was allowed to rejoin the school so he would be present during the visit of the king.

Dia al-Azzawi - Ishtar My Love, 1965, oil on canvas, 89 x 77 cm, Arab Museum of Modern Art, Qatar Foundation, Doha (Left) and Dia al-Azzawi - Three States of One Man, 1976, oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm, Private Collection (Right)

Dia al-Azzawi - Ishtar My Love, 1965, oil on canvas, 89 x 77 cm, Arab Museum of Modern Art, Qatar Foundation, Doha (Left) and Dia al-Azzawi - Three States of One Man, 1976, oil on canvas, 120 x 100 cm, Private Collection (Right)

Caught Between Histories

Despite his own engagement in politics, the art al-Azzawi made in his youth was not revolutionary. He was simply learning technique and mastering his craft. Having access to few resources from which he could learn about world art history, much of his work focused on illustrating the folklore of his culture. Later, while working toward his archaeology degree from the College of Arts, he began taking night courses in European art history at another school. By combining the aesthetic histories of Middle Eastern and European culture he developed a much broader aesthetic perspective highlighting the universalities inherent in both. This approach aligned him with a group of Iraqi artists called The Pioneers, who were dedicated to creating a cultural bridge between ancient and contemporary Iraq.

But although The Pioneers were influential and successful, they were also nationalistic. Ultimately al-Azzawi decided that to focus only on one national perspective would prevent him from achieving an understanding of larger truths. He decided he wanted to expand his work to address the entire Middle East, not just Iraq, and wrote a manifesto that advocated for artists to engage actively in the political and cultural issues of their own time. In 1967, in what came to be called the Six Day War, Israel attacked and decisively defeated the armies of Egypt, Syria and Jordan, taking over wide swaths of territory from all three countries and displacing roughly half a million people with various religious, cultural and national ties. Following the war, even those not displaced lost their freedom to speak out against the Israeli government. The sight of so many people being turned into refugees and reduced to silence in the face of widening, region-wide cultural conflict caused al-Azzawi to dedicate himself to statelessness as a major issue he wanted to address in his art.

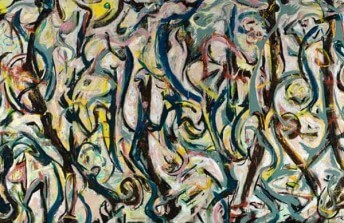

Dia al-Azzawi - My Broken Dream, 2015-2016, Acrylic on paper mounted on canvas, 166 9/10 × 393 7/10 in, 424 × 1000 cm, © the artist and Meem Gallery, Dubai

Dia al-Azzawi - My Broken Dream, 2015-2016, Acrylic on paper mounted on canvas, 166 9/10 × 393 7/10 in, 424 × 1000 cm, © the artist and Meem Gallery, Dubai

I Am The Cry

It was at the height of his own cultural, political and artistic awakening that al-Azzawi watched in dismay as the Ba’ath Party gained control over Iraqi politics. Under the guise of unifying the Arab world, the party plunged the culture into a dark time of war and totalitarianism. After being released from his military obligation to the Ba’ath Party, al-Azzawi left Iraq for the first time, to attend a summer printmaking workshop in Austria. This experience made him aware of just how stifled his creative progress had been. The following year he left Iraq for good, moving to London where he has lived in self-imposed exile since. But he has never stopped devoting himself to the important work of fighting for the betterment of his native culture. From his studio in London he has spent the past several decades speaking out through his art, giving a voice to people across the Middle East who are being repressed and who he sees as voiceless. “I feel I am a witness,” he has said. “If I can give a voice to somebody who has no voice, that is what I should do...You cannot be an outsider.”

One of the largest opportunities al-Azzawi has had to express himself came just last year, as a pair of retrospectives held simultaneously at two museums in Qatar undertook a monumental attempt to offer what really ended up only being a glimpse of his long and varied career. Titled I am the cry, who will give voice to me? Dia Azzawi: A Retrospective (From 1963 until tomorrow), the shows featured more than 350 works by al-Azzawi. Ranging from his earliest days in Baghdad all the way to the present day, the exhibitions included examples of his drawings, paintings, textiles, art books, prints, and what he refers to as his object art pieces—three dimensional, multi-media objects that straddle the line between sculpture and assemblage. It was in that interview with the Telegraph, which he gave back when these retrospectives were first opening, that al-Azzawi offered the first hint about the nature of his newest work, Hanging Garden of Babylon. When asked what would be next for him, al-Azzawi responded, “I want to make things that are monumental, and for this, sculpture is the most effective.” Whether it will, in fact, be effective is something only time will be able to reveal. But this latest work by al-Azzawi certainly calls attention to the idea of what it means to have a voice, and its timing and location make it a perfect monument to our difficult and confusing times.

Featured image: Dia al-Azzawi - Hanging Garden of Babylon, 2015, Bronze, 400 x 230 x 80 cm, Courtesy of the artist and Mathaf - Arab Museum of Modern Art, Qatar Museums, Doha

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio