Helen Frankenthaler Paintings Celebrated in Dual Retrospectives

Jul 20, 2017

Helen Frankenthaler paintings are common sights at many of the best museums in the world, as well as at many prestigious Modern and Contemporary art fairs and auctions. But far fewer people have had the chance to experience being in the presence of a Helen Frankenthaler woodcut. It is perhaps not so surprising that her woodcuts are less appreciated than her paintings. Frankenthaler first made her name as a painter, and her achievements in that realm continue to stand out today as radical. She painted one of her most famous paintings when she was only 24 years old. And though she started experimenting with printmaking in her 30s, she did not even begin making woodcuts until she was in her mid-40s. But thanks to a pair of Frankenthaler exhibitions that opened concurrently earlier this month at the Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, fans of this extraordinary artist now have a rare opportunity to experience some of the finest available examples of both aspects of her oeuvre. The exhibition As in Nature features twelve large-scale Helen Frankenthaler paintings, tracing her career from its early phases, before she invented her breakthrough “soak-stain” technique, through to the more painterly, experimental works she made in the 1990s. Simultaneously, in a separate gallery at The Clark, the exhibition No Rules features a selection of twelve Helen Frankenthaler woodcuts. Together the two exhibitions offer a rare glimpse of the diverse range of abilities that led Frankenthaler to become one of the most influential artists of the past century.

As in Nature: Helen Frankenthaler Paintings

Legend has it that Helen Frankenthaler invented the technique that made her famous in 1952. Known as the “soak-stain” technique, it involved working horizontally on the floor and applying paint that had been thinned with turpentine directly to unprimed canvas. The paint thus became infused into the fibers of the canvas, transforming the image and the surface into one entity. The first painting she is known to have made with this technique is called Mountains and Sea. The story Frankenthaler told about its creation was that she had just returned from a trip to Nova Scotia. She said she carried the beautiful landscapes of that place back with her in her memories and felt that she also carried them in her arms. She wanted to paint them, but was not interested in simply copying their images. Rather, she wanted to communicate their essence, their spirit, through abstract means. About what she hoped to achieve, Frankenthaler said, “I think that, instead of nature or image, it has to do with spirit or sensation that can be related by a kind of abstract projection.”

By laying her canvas on the floor she found a way to physically engage with the work, so that the images she carried with her in her arms could come forth directly like sweat pouring out of a farmer working a field. By thinning her paints she was able to achieve the same translucency with oils and acrylics as could previously only be achieved with watercolors. That translucency offered a way to communicate the ephemerality of the landscapes she now only had in her memory. By not priming her canvas she allowed the paint to determine its own trajectory, guided by her suggestions and manipulations but not determined entirely by them. It was a revolutionary approach. It was quickly adopted by other painters, and it was heralded by critics as a radical change, one that has since largely been discussed in quite academic terms. But the roots of the technique were not in academia. They had nothing to do with trends or art history. They were simply intuitive.

Helen Frankenthaler - Mountains and Sea, 1952, Oil and charcoal on unprimed canvas, 86 3/8 × 117 1/4 in

Helen Frankenthaler - Mountains and Sea, 1952, Oil and charcoal on unprimed canvas, 86 3/8 × 117 1/4 in

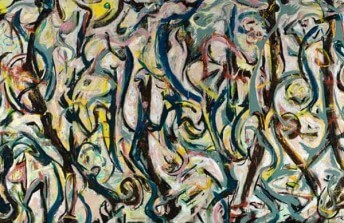

Sensation Over Explanation

The selection of works on display in As in Nature stands as a testament to the fact that Frankenthaler was far less of an academician trying to push painting forward in history, and far more of a contemplative artist: someone who was in search of something, who was sowing, planting, working and hoping. A perfect example is the paintings Milkwood Arcade, a stunning, off-kilter composition of forms frozen in a metamorphosis between harmony and disarray. Like so many of her works, this painting begs to simply be looked at deeply, not so an explanation can be contrived, but so that a sensation can be experienced.

And just in case any doubt remains that Frankenthaler was more about feelings than academics, As in Nature eliminates it by including so many paintings of such enormous scale. The prime example has to be the monumental Off White Square. Measuring more than two meters high and six-and-a-half meters long, it is more of an environment than an image. Standing in its midst, color is transformed into emotion. Within the spaces where the layers of paint have absorbed into each other, a primordial sense of possibility opens up. It proves definitively that though her best-known technique was groundbreaking, for Frankenthaler it was only a means for the abstract projection of the spirit and sensation of nature.

Helen Frankenthaler - Milkwood Arcade, 1963, Acrylic on canvas, 86 1/2 x 80 3/4 in, 219.7 x 205.1 cm

Helen Frankenthaler - Milkwood Arcade, 1963, Acrylic on canvas, 86 1/2 x 80 3/4 in, 219.7 x 205.1 cm

No Rules: Helen Frankenthaler Woodcuts

No Rules, the concurrent exhibition of Helen Frankenthaler woodcuts, derives its from what is perhaps the most famous Helen Frankenthaler quote: “There are no rules...that is how art is born, that is how breakthroughs happen. Go against the rules or ignore the rules, that is what invention is about.” It was precisely the spirit of invention that led Frankenthaler to completely reinvent the craft of woodcut printing in order to achieve the specific aesthetic qualities she sought. Traditionally, woodcut prints have a look that is defined by white lines and hard edged shapes. But Frankenthaler wanted to achieve a softness in her woodcut prints that could convey the same sense of ethereal beauty that she coaxed from her paintings. In order to achieve her goals she created an individualized process that was time consuming and complex. The results were spectacular, and are on full view in this exhibition.

No Rules begins with East and Beyond, the first woodcut print Frankenthaler completed. The sensual forms melt into each other in soft, organic ways. The rich, vibrant colors almost seem painted on. It looks nothing like any woodcut print that preceded it. Next on view is a selection of woodcuts Frankenthaler collaborated on with two Japanese masters of the craft, woodcarver Reizo Monjyu and printer Tadashi Toda. Working with them on traditional techniques, Frankenthaler embraced the idea of allowing the grain of the wood to show through in the final print. Next the exhibition offers a glimpse of the manipulated papers Frankenthaler experimented with in the 1990s in such woodcuts as Freefall and Radius. And finally, the exhibition concludes with some of the final and finest woodcuts Frankenthaler made, including the monumental Madame Butterfly, a two meter long, 102-color woodcut print triptych made using 46 separate woodblocks and printed handmade paper.

Helen Frankenthaler - Madame Butterfly, 2000, One hundred two color woodcut from 46 woodblocks, 41 3/4 x 79 1/2 in, 106 x 201.9 cm

Helen Frankenthaler - Madame Butterfly, 2000, One hundred two color woodcut from 46 woodblocks, 41 3/4 x 79 1/2 in, 106 x 201.9 cm

Remembering a Legend

It has been almost six years since Helen Frankenthaler died. Though she was one of the most influential American artists of the past century, her legacy, ironically, is often diminished by the very breakthrough that helped jumpstart her career. In 1952, the year she completed her first “soak-stain” painting, the various forces that conspire to set trends and make stars in the American art world happened to also be searching for the next big thing. Abstract Expressionist artists like Jackson Pollock had enjoyed nearly a decade of attention for their aggressive, impasto, angst-ridden approach to their work. The sublime, flattened, contemplative nature of paintings like Mountains and Sea positioned Frankenthaler as the perfect counterweight. But that single accomplishment was truly only the beginning of a career that underwent a multitude of evolutions big and small, and produced an oeuvre worth far more consideration than Frankenthaler has thus received.

By staging these two concurrent exhibitions, As in Nature and No Rules, The Clark has taken an elegant step toward expanding the legend of Helen Frankenthaler. For starters, these two exhibitions feature works that come from two mostly private collections—that of the William Louis-Dreyfus Foundation and that of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation—so most of the works have never been exhibited publicly together before. Secondly, by selecting such large-scale works these exhibitions showcase the magnitude of the physical labor that went into their creation, something that so frequently gets lost when viewing a single painting in a museum, and especially when looking at images online. Thirdly, these exhibitions open the door to future retrospectives that may ultimately help contextualize Helen Frankenthaler as the prolific and multifaceted artist that she was. As in Nature: Helen Frankenthaler Paintings is on view at the Clark Art Institute until 9 October 2017, and No Rules: Helen Frankenthaler Woodcuts is on view in a separate wing of the same building until 24 September 2017. Admission is $20, or is free for members, students with a valid ID, children under 18, and for members of the Clark library pass program.

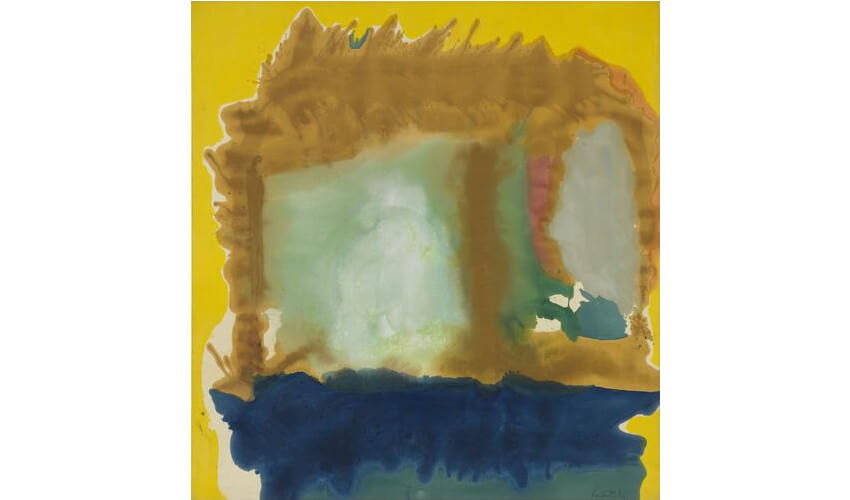

Helen Frankenthaler - Interior Landscape, 1964, Acrylic on canvas, 104 3/4 x 92 3/4 in, 266 x 236 cm, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Helen Frankenthaler - Interior Landscape, 1964, Acrylic on canvas, 104 3/4 x 92 3/4 in, 266 x 236 cm, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Featured image: Helen Frankenthaler - Aquatint etching, woodcut & pochoir with hand-coloring, 35 5/8 × 68 1/4 in, 90.5 × 173.4 cm

All photos © 2017 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York, New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio