Inside Donald Judd's MoMA Blockbuster

Feb 26, 2020

Though he passed away in 1994, Donald Judd remains one of the most influential American artists ever. This spring, we will have a chance to reconsider his legacy thanks to the retrospective Judd, which will open on 1 March 2020 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (MoMA). The first Judd retrospective in the United States in three decades, it will give an entire generation of viewers who have only seen his work in limited doses at art fairs, in books or on the internet (unless they have made the trek to Marfa, Texas, where scores of Judd works are on permanent display) extraordinary access to the Judd oeuvre. According to the press release, Judd will highlight “the full scope of [his] career through 70 works in sculpture, painting, and drawing.” Some irony might be evident in that statement, however, to anyone familiar with Specific Objects, the seminal essay Judd published in 1965 about the “new work” being done at that time. This essay demonstrates how wary Judd was of using delimiting terms like painting and sculpture. He tries to get beyond them by using phrases like specific objects, two-dimensional and three-dimensional. It also shows how concerned Judd was with the notion that art, in order to be good, has to be novel and totally thought out. He writes, “New work always involves objections to the old, but these objections are really relevant only to the new. They are part of it. If the earlier work is first-rate it is complete.” By peeling back the multitude of superficialities baked into art language, Judd lays the groundwork for a better standard by which to talk about his own art. That standard is based on the avoidance of vanity and ego, and the eradication of speculation. He wanted his works only to be acknowledged for what they actually are, and to be judged on their unique merit regardless of who made them. Yet, here we are, 26 years after his death, still basing the value (especially the financial value) of his oeuvre on the fact that it is his, and still using the same terminology to describe it that he tried to subvert in the 1960s. Maybe that means Judd failed in his attempt to change the way we talk about art, but it takes nothing away from the powerful statement he made with his work.

Boxes, Platforms and Shelves

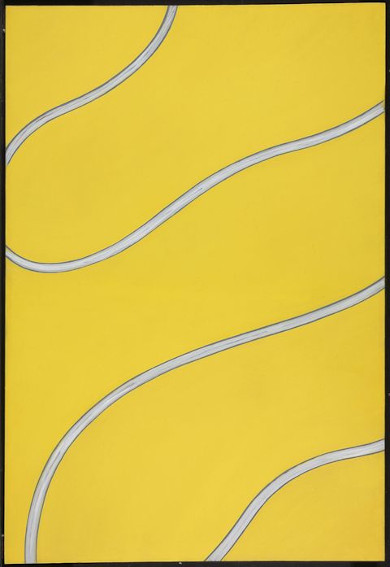

Judd at MoMA unfolds chronologically, tracing the evolution of his vision from the early 1960s, when he experimented with a relatively lively range of forms, through the 1990s, by which time he all but settled on a limited selection of fabricated forms resembling—but not intended to be thought of as—boxes, platforms and shelves. In the early stages of his career, Judd was also a prolific art critic, meaning that in addition to his own search for a unique aesthetic voice he was constantly going to see the work of other artists and writing about it. The art field at that time was rife with radical experimentation, resulting in a rush of new so-called movements, each of them named, capitalized, then abandoned faster than the last. In his search for something that could rise above the classical mess, Judd turned to what he saw as the perfect manifestation of the modern world: industrialization. He perceived beauty and simplicity in the fabricated forms he saw at the hardware store, and was enamored with their perfect finishes.

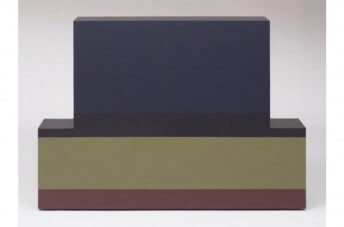

Donald Judd - Untitled, 1960. Oil on canvas, 70 × 47 7/8″ (177.8 × 121.6 cm). National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa © 2020 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

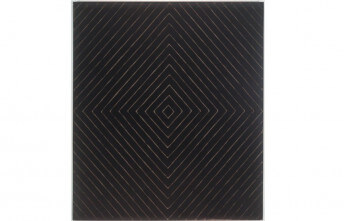

The earliest attempts Judd made to express the beauty of the world of fabricated forms were expressed through a wide array of geometric constructions, some resembling steps and platforms, and others taking on the pre-arranged forms dictated by the prefabricated items he used to make the work. Over time, however, the logic of his concept guides Judd almost entirely towards squares and rectangles. He uses this limited range of forms not to express mass or volume, but to show how space and color can be endlessly reconfigured. Each form is divided up differently on the inside, so even if you feel like you are seeing the same form over and over again, you are actually encountering innumerable variations on the arrangement of space. Each shelf and stack follows a similar logic, as simple changes in surface finishes and colors demonstrate the endless potential of the system Judd created. Along the way, the preparatory sketches Judd created offer an answer to those who deny that something fabricated by a machine can be called art.

Donald Judd - Untitled, 1968. Stainless steel and amber Plexiglas; six units, each 34 × 34 × 34″ (86.4 × 86.4 × 86.4 cm), with 8″ (20.3 cm) intervals. Overall: 34 × 244 × 34″ (86.4 × 619.8 × 86.4 cm). Layton Art Collection Inc., Purchase, at the Milwaukee Art Museum © 2020 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: © John R. Glembin

Rationality and Form

One of the most important takeaways from Judd at MoMA will be the realization that Donald Judd operated in a rational world. I have come to think of him as the Einstein of the art world. Like Einstein, Judd endlessly contemplated the problems he and his colleagues were facing, and challenged himself to develop theories that might make sense of his amorphous and misunderstood field. Like Einstein, who believed physics had to be rational, and that all forms that exist in the universe must exist according to the laws of space and time, Judd believed that human creativity is rational, and that the creation of forms should follow logical steps. Readings of both the Special Theory of Relativity and Specific Objects will reveal that neither Einstein nor Judd believed in magic.

Donald Judd - Untitled, 1989. Clear anodized aluminum with amber acrylic sheet, 39 3/8 × 78 3/4 × 78 3/4″ (100 × 200 × 200 cm). Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland © 2020 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: © Tim Nighswander/Imaging4Art

As brilliant as Einstein was, however, he was sometimes wrong. The fundamental basis of our most cutting edge technology today relies on quantum entanglements, a strange aspect of quantum physics that Einstein insisted could not exist. Likewise, based on the various non-hierarchical, unexpected trajectories the art field has taken since Judd wrote Specific Objects, it would seem that Judd was also wrong about some things. And just as quantum physics offers an alternative to Einstein, many abstractionists have offered convincing alternatives to Judd. Nonetheless, this exhibition comes at a time when the art field is once again driven by ego, vanity, story, narrative, research, and other such pretenses for cramming meaning into art. Perhaps Judd, whose work has no vanity and no story to tell, will suggest to a new generation of artists that their work might benefit if they try a little harder to take themselves out of it in service to making something novel, rational, and complete.

Featured image: Donald Judd - Untitled, 1991. Enameled aluminum, 59″ × 24′ 7 1/4″ × 65″ (150 × 750 × 165 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Bequest of Richard S. Zeisler and gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller (both by exchange) and gift of Kathy Fuld, Agnes Gund, Patricia Cisneros, Doris Fisher, Mimi Haas, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, and Emily Spiegel. © 2019 Judd Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: John Wronn

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio