A Word on the 100 Untitled Works in Mill Aluminum by Donald Judd

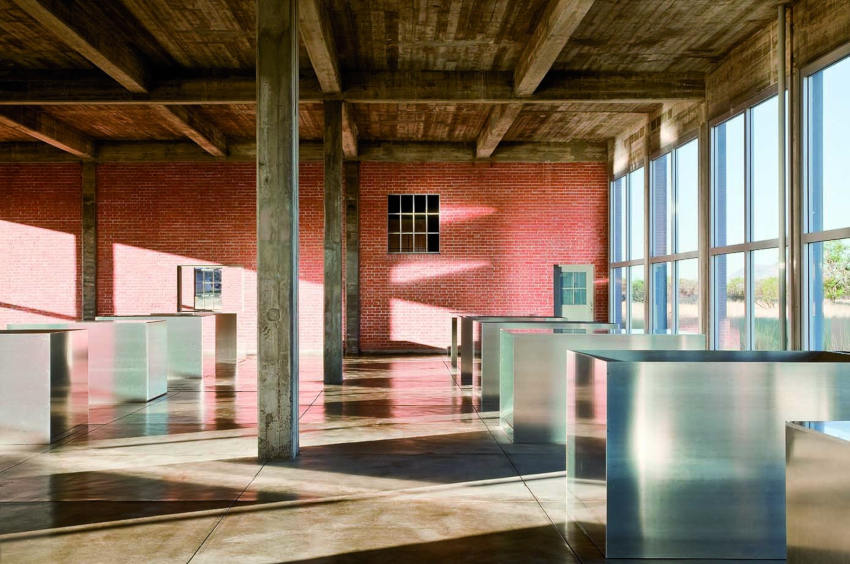

Few contemporary art destinations are more notable than Marfa, Texas. Though some complain that the mecca of Modernist asceticism has lately become more of a laboratory of Post-Modern avarice, at least one Marfa exhibition—a monumental installation by Donald Judd titled “100 untitled works in mill aluminum” (1982 — 1986), which inhabits two former artillery warehouses on the grounds of the Chinati Foundation—still retains all of its original, beautiful, conceptual tension. In classic Judd style, the self-referential title of the work explains exactly what it is: 100 identically-sized aluminum boxes. The boxes are exhibited in rectangular formations inside the two massive, rectangular buildings, lined up symmetrically within the open spaces. Rows of identical, square windows that cover the exterior walls of the buildings reveal the boxes to passersby and allow the blazing sun to gleam off the metal edges of the boxes. The word “mill” in the title refers to the natural “mill finish” rolled aluminum has when it comes out of the extruder. That important bit of information references the anonymous industrial fabrication process that was so essential to what Judd did; it made every piece exactly the same, and removed any trace of the hand of the artist. But in the case of this installation, every aluminum box is not exactly alike. Although the outer dimensions of each box are identical—41 x 51 x 72 inches—each box is also unique, thanks to individualized inner compositions created by aluminum dividers that separate the interior spaces into geometric variations. Though Judd stopped at 100, he clearly could have come up with infinitely more variants. The choice of 100 was arbitrary. Lurking somewhere within that cosmic realm of aesthetic ubiquity and structural randomness is the fleeting sense of ephemeral transcendence that continues, year after year, to lure thousands of pilgrims to this dusty outpost in the American Southwest, regardless of how much money a cup of coffee or a hotel room there now costs, or of the increasing availability of the seeming opposite of the Judd ethic: artisanal, handcrafted everything.

The Middle of Somewhere

On my first visit to Marfa in 2015, I stayed at The Hotel Paisano, an elegant, Mediterranean-style structure built in the 1930s. This was a splurge for me and my wife—a writer and an artist. The place was designed from the beginning to cater to elites. When it was built, the town was little more than a glorified railroad stop, and home to a military base where American pilots trained, and prisoners of war were housed. Judd first encountered Marfa on his way to serve in the Korean War. The desolation of the place impressed him. He returned in 1973 and bought up most of the then-abandoned real estate in town. He did not, however, buy The Hotel Paisano. He went more for the unadorned style of architecture exemplified by the two former military buildings in which “100 untitled works in mill aluminum” is displayed. The simple, anonymous aesthetic of such buildings echoed his growing fascination with so-called Minimalist art (a label Judd famously rejected when it came to his own work).

Donald Judd - 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986. Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas. Photo by Douglas Tuck, Judd Art © Judd Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

For years prior to visiting Marfa, I heard associates tell tales of the city. Every one painted the town as a dusty outpost in the middle of nowhere, full of cheap drinks and scant other provisions. I learned that this is no longer the case. The mythos as a place of rough and tumble artists, enlightened locals, and little else comes from the monk-like persona Judd has been granted since his death in 1994. He has become like the ultimate American representative of ars gratia artis—true art, devoid of materialistic, philosophical, or ethical value. He did, after all, abandon the New York art world at the height of his success, moving instead to this nearly abandoned, inaccessible desert town, where he could make site-specific works that could never be sold or moved. But since his death, the city has grown into a funny sort of playground for wealthy art tourists who fly in on private jets, and dine on fine food and drink that, like them, has traveled from afar, while nearly half the local population lives below the poverty line.

Donald Judd - 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986. Courtesy of the Chinati Foundation. Art © Judd Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Unauthorized Persons Not Allowed

In spite of the overtly inequitable culture that now occupies Marfa, the work Judd left behind remains proudly, anarchically egalitarian. When standing in their presence, there is no denying that each object Judd helped bring into the world remains aesthetically equal to each of its companion objects in stature and meaning, or lack thereof. The utopian aspirations that guided Judd are epitomized in “100 untitled works in mill aluminum.” To fully appreciate this installation, you must see it in person. You must move. It cannot be captured in a single photograph. It changes constantly with each shift of the sun and clouds. Even the boxes move slightly along with meteorological changes.

Donald Judd - 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986. Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas. Photo by Douglas Tuck, Judd Art © Judd Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Ane mystery of “100 untitled works in mill aluminum” comes not from the work, but from the space in which it sits. Although Judd changed the roof and exterior of the buildings, he left behind some stencils that had been painted on the interior walls when German POWs were housed there. One reads, “ZUTRITT FÜR UNBEFUGTE VERBOTEN,” which means “Unauthorized persons not allowed.” Why keep this remnant of history? I consider it a key aspect of the inherent tension of the installation. It evokes the truth of humankind. It speaks to what should not be erased. It also hauntingly references the unequal culture that has arisen in this tiny, remote place, as those born and raised here feel increasingly as though they are the unauthorized. There is something essential about the contradiction this sign represents. It speaks both to why Judd built “100 untitled works in mill aluminum,” and why he rejected the term Minimalism. His work is not only about reduction and sameness. It is also about the uniqueness of what remains.

Featured image: Donald Judd - 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986. Photo credit: Donald Judd, 100 untitled works in mill aluminum, 1982-1986. Permanent collection, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, Texas. Photo by Douglas Tuck, courtesy of the Chinati Foundation. Donald Judd Art © 2017 Judd Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio