London to Get Re-acquainted with the Work of Elaine Sturtevant, Courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac

Jan 29, 2018

If you are a fan of philosophy and art, mark your calendar—the work of Elaine Sturtevant, known professionally as Sturtevant, returns to London this year, with the exhibition Vice Versa. On view from 23 February until 31 March 2018 at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac – Ely House, it is the first posthumous survey of her work in the UK since Sturtevant died in 2014. London was also the site of the last major survey of her work before she died, at Serpentine Galleries in 2013. While assembling that show, Sturtevant perceived she was staging a masterwork—a complete, self-explanatory example of everything she had been trying to communicate during the previous five decades of her professional career. It was a career filled with endless criticism, brought about by an inherent misunderstanding about the meaning of what Sturtevant was doing. Since her first solo exhibition in 1964, she was consistently derided as one of the most controversial artists in the Western world. That controversy stemmed from her “repetitions” as she called them—near replicas of the works of other artists, done in the same style and using the same techniques. These works attracted near universal ire, causing Claes Oldenburg to allegedly threaten Sturtevant with death, and causing some gallerists representing the artists whose work she repeated to purchase and destroy her works. One one hand, it is a pity that Sturtevant is no longer present to defend her work—she was more intelligent than her critics, and her responses to their remarks were a pleasure to read. But on the other hand, it is a blessing Sturtevant has moved on. Now it is up to us to contemplate for ourselves the meaning of her work, and to decide the extent of its lasting value to the culture.

The Regularity of All That Happens

To understand the ire Sturtevant aroused with her early work, you have to consider the culture surrounding her first solo show. It was 1964 in New York. The art world was dominated by the art market. Celebrities and fortunes were being made over night—a relatively new phenomenon. Her first exhibition targeted some of the biggest art stars of the moment, including George Segal, the pop art sculptor known for stark white human figures, and Andy Warhol, who was by this time an international star. In her exhibition, Sturtevant repeated their works. She exhibited sculptures in the exact style of Segal, and flower prints made using the exact technique Warhol had used to make the flower prints he himself had exhibited nearby just weeks before.

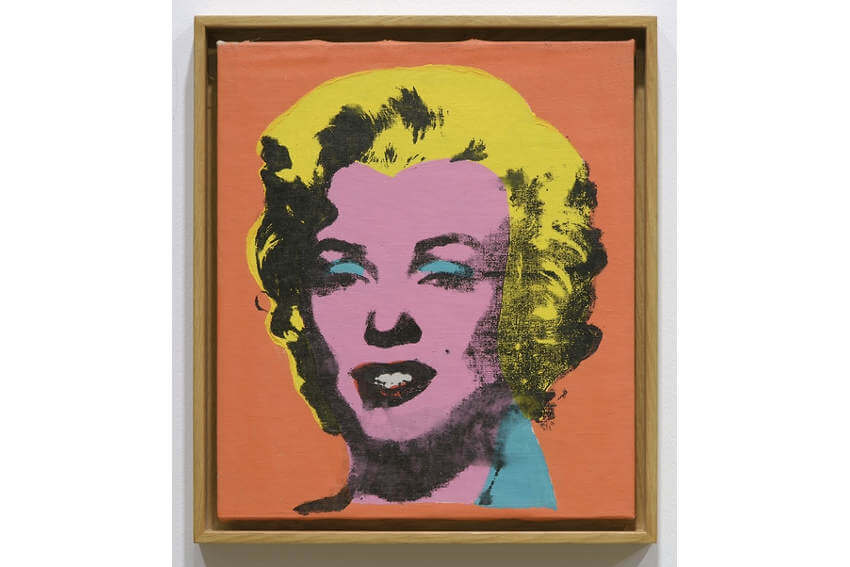

Elaine Sturtevant - Warhol Marilyn, 1973, Synthetic polymer silkscreen and acrylic on canvas, 45 x 39.5 x 4 cm, Collection Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg

Elaine Sturtevant - Warhol Marilyn, 1973, Synthetic polymer silkscreen and acrylic on canvas, 45 x 39.5 x 4 cm, Collection Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg

The reaction from most critics who saw the show was outrage. Even though Warhol had himself taken his flower image from a magazine, they called Sturtevant a hack for repeating it. Especially baffling to them was that Warhol approved of what Sturtevant did, and had actually let her use the same screen he had used to make his flower prints. Warhol understood what Sturtevant was doing, because in some ways he was doing the same thing. But the general public was taken aback. Some people called Sturtevant a forger; some mistakenly defended her, saying she was paying homage to these other artists; still others considered the work to be a mockery, like Dadaist anti-art. Few acknowledged her own explanation, that she was “thinking about the under-structure of art. What is the power, the silent power, of art?”

Elaine Sturtevant - Lichtenstein Girl with Hair Ribbon, 1966 - 1967, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 120 x 120 cm, © Estate Sturtevant. Photo: Max Yawney

Elaine Sturtevant - Lichtenstein Girl with Hair Ribbon, 1966 - 1967, Oil and acrylic on canvas, 120 x 120 cm, © Estate Sturtevant. Photo: Max Yawney

The Unity of All That Exists

Before becoming an artist, Sturtevant earned Bachelors and Masters degrees in psychology. She was an avid reader of philosophy, especially the work of her favorite philosopher, Baruch Spinoza. According to Hans Ulrich Obrist, director at Serpentine Galleries and a longtime confidant of the artist, Sturtevant left behind one great unrealized project when she died: “to write a libretto for an opera about the philosopher [Spinoza].” Like Sturtevant, Spinoza was considered a heretic. In his writings, he audaciously concluded that god and nature are one, mind and body are one, and all things in the universe are connected. He believed there is no such thing as divine intervention in human life, and that the hierarchy of earthly authority that supposedly stems from divine authority is therefore false. Since we all come from the same source—a stoic, rational, disinterested, god-nature being—he felt we are all equal in our capabilities and potentialities. He furthermore proposed that there is a regularity and predictability to all things that occur—meaning every occurrence is a repetition of countless occurrences that came before it, and a premonition of countless more repetitive occurrence yet to come.

Elaine Sturtevant - Johns Flag, 1966, Collage and encaustic on canvas, 34 x 44.2 cm, Collection Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg

Elaine Sturtevant - Johns Flag, 1966, Collage and encaustic on canvas, 34 x 44.2 cm, Collection Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg

When I look at the work Sturtevant did through the lens of those philosophies, I see it as a definitive statement that we, like the contemporaries of Spinoza, have put our faith in the wrong things. Spinoza was telling people not to seek divine help, but rather to embrace ethics and rationality, and to understand they are part of nature. Sturtevant was telling us not to put faith in art or those who make it. She was demonstrating that a painting, a film or a sculpture, and the processes from which they emerge, are no different than a leaf, a blade of grass or a snowflake, and the processes from which they emerge. Even if they have superficial differences, they are not wholly unique. They are slight variations of the same thing, re-made over and over again, from the beginning of time until the end of time. To worship artists or artworks as though they have inherent power is foolish, and to believe in total originality is like waiting for Godot. But as this upcoming exhibition, Vice Verso, will show, Sturtevant was not mocking us, or mocking art. She was pointing out that we should enjoy, appreciate and celebrate art for what it is. But to do that, we need to try harder to understand its nature, and to understand ourselves.

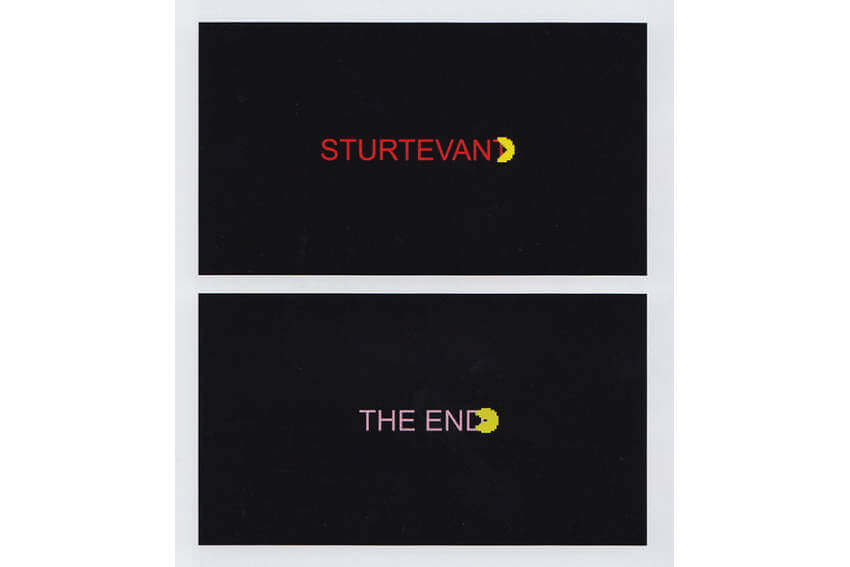

Elaine Sturtevant - Pac Man, 2012, HD cam - Metallic tape, One camera video, Installed on flat screen, RT: 1'15'', Ed. 2 of 5, 2AP, © Estate Sturtevant, Paris

Elaine Sturtevant - Pac Man, 2012, HD cam - Metallic tape, One camera video, Installed on flat screen, RT: 1'15'', Ed. 2 of 5, 2AP, © Estate Sturtevant, Paris

Featured image: Elaine Sturtevant - Warhol Silver Clouds, 1987, Mylar and helium, 88.5 x 126.2 cm, © Estate Sturtevant, Paris

All images courtesy Thaddaeus Ropac, London · Paris · Salzburg, all images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio