The Anti-Art of Dadaism and its Paintings

The term Dadaism describes a time in art history when artists confronted the absurdity of human culture. The author Kurt Vonnegut once said, “Take life seriously but none of the people in it.” Though not intended to do so, that sentiment comes close to explaining the Dada viewpoint. Dadaism paintings run the gamut from works of collage, to technical diagrams, to propaganda, to works of pure abstraction. Style was not integral to Dadaism, nor was any other categorical description of a work of art. Dadaism was a reaction against cultural logic, which the Dadaists blamed for leading humanity to the brink of suicide. As Western culture’s first manifestation of “anti-art,” Dadaism challenged every aesthetic phenomenon that pre-dated it, and shaped all that were to come.

Art vs. Art

Dadaism emerged around 1915, with manifestations simultaneously and independently evolving in both New York City and Zurich. World War I had started in 1914, thrusting humanity into its first mechanized, global conflict. Twenty million people died in WWI, making it the second bloodiest human conflagration in history up to that point, after the Mongol Invasions of the 13th Century. The poverty, famine, disease and destruction it caused would lead to millions more deaths and countless injuries in the years after.

In the midst of this horror, the artists that became known as Dadaists lashed out against the bourgeois logic that they believed was responsible for the war. They rejected all previous manifestations of art, which they perceived as having been supported and justified by the same paradigm. Sensing that all of human culture had lost its meaning, the Dadaists made work that followed no logic, that defied allegiances or descriptions, that rejected any unifying philosophy and resisted any kind of logical cultural critique.

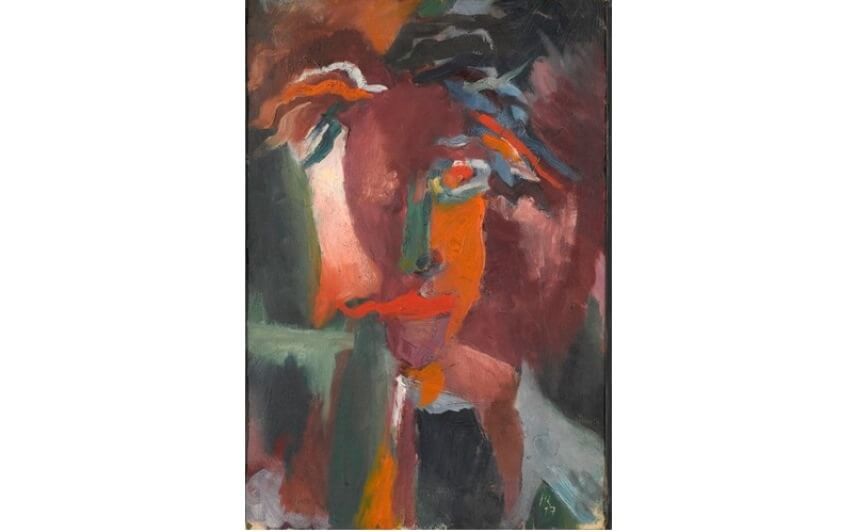

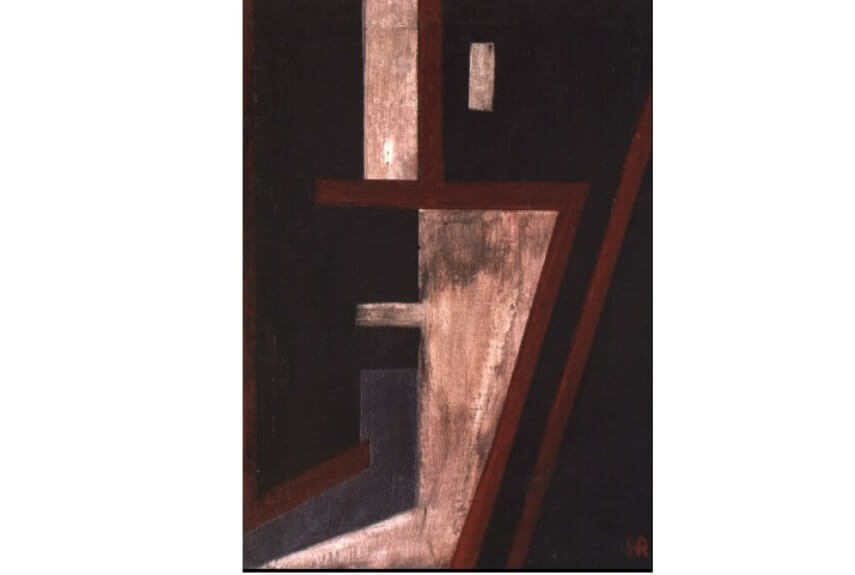

Hans Richter - Portrait visionnaire (Self Portrait), 1917. Oil on canvas. 53 x 38 cm. Museo d'Arte di Lugano, Switzerland.

Abstract Dadaism Paintings

Many Dada artists were multi-disciplinary in their approach. Dadaism manifested across all aesthetic forms, from literature to musical theater to photography to sculpture, and on and on. Dadaist paintings were influenced by some of the movements directly proceeding Dadaism, such as Analytic Cubism, Collage, and the works of abstract painters like Kandinsky. Nonetheless, it is incorrect to say that any Dadaist painters were intentionally trying to be abstract, since the Dada outlook denied the validity of labels such as representation or abstraction.

Nonetheless, many Dadaism paintings do fit in with the internal logic of abstraction, in that they interact with viewers not through representational content, but rather through a vocabulary based on line, color, form, surface, materiality and dimensionality. Of the dozens of artists associated with Dadaism, the three who regularly made such work were Jean Arp, Francis Picabia and Hans Richter.

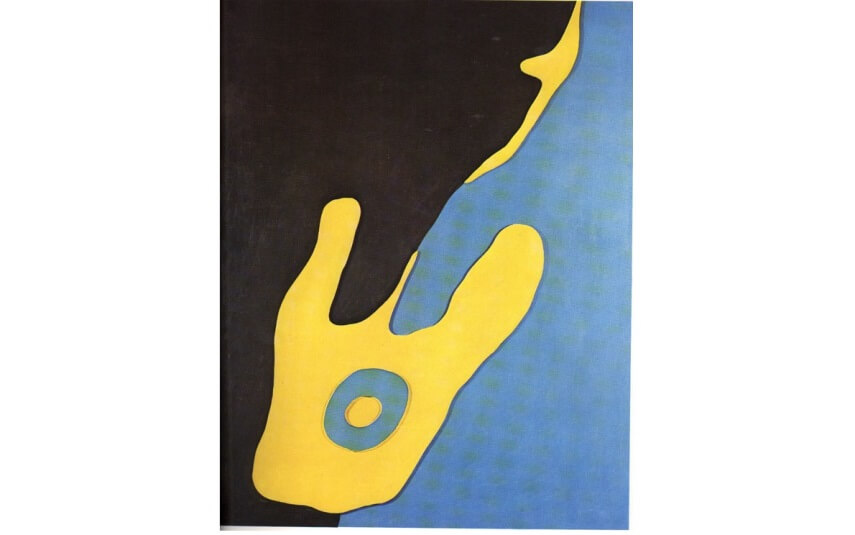

Jean Arp - Configuration, 1927. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Arp

Jean Arp was known by two names. When speaking French, he called himself Jean. When speaking German, he called himself Hans. Arp met Wassily Kandinsky in Munich in 1912. Arp was influenced by Kandinsky’s writings on pure abstraction. But when the war broke out he did not want to stay in Germany, where he feared he would be forced to fight. According to Arp’s own accounts, he fled Germany and moved to Zurich at the outbreak of WWI after pretending to be insane in order to avoid being drafted. After arriving in Zurich, Arp became a founding member of Dada.

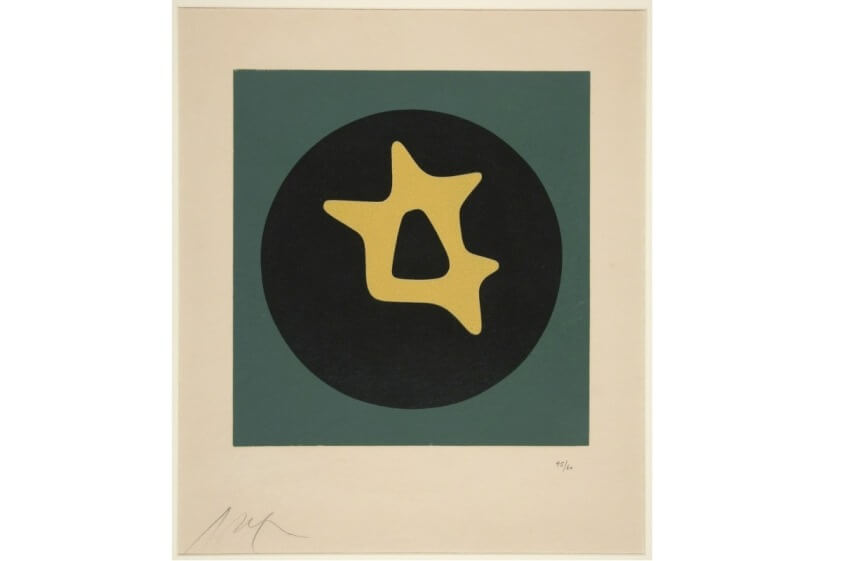

Arp’s abstract paintings, collages and prints incorporate mixtures of geometric and organic forms. The color palette is restrained and the hues subdued. His lines are sometimes meticulous, and other times almost vibrate with a sort of hand-made delicacy. Through these works, Arp captures the morphing essence of the subconscious and the potential calmness available in imagery that exists outside of objective representation.

Jean Arp - Untitled, 1922. Color screenprint. 34.4 × 32.6 cm. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

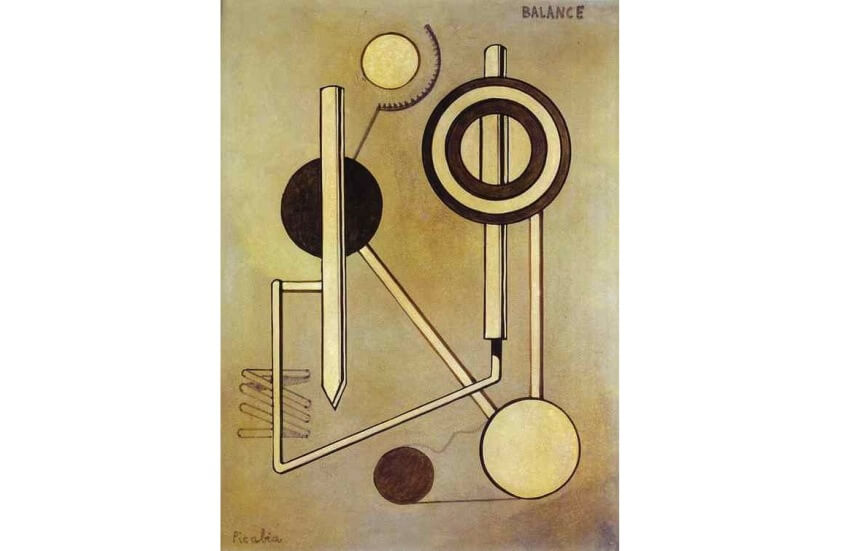

Francis Picabia

Francis Picabia was a typographer in addition to being a painter. His roots are evident in that many of his works contain text of some sort or another. Picabia was classically trained as a painter, but in his 30s became influenced by Cubism. He painted a number of famous Cubist paintings before joining Dada and dramatically shifting the nature of his work.

Francis Picabia - Balance, 1919. Oil on cardboard. 60 x 44 cm. Private collection

Picabia’s Dadaist paintings explored absurd mechanical formulations, connecting geometric shapes and quasi-industrial concoctions in order to create compositions that seem part geometric abstraction and part machine. After spending more than half a decade creating such work, Picabia broke away from the Dadaists and pursued a more purely abstract direction in his work.

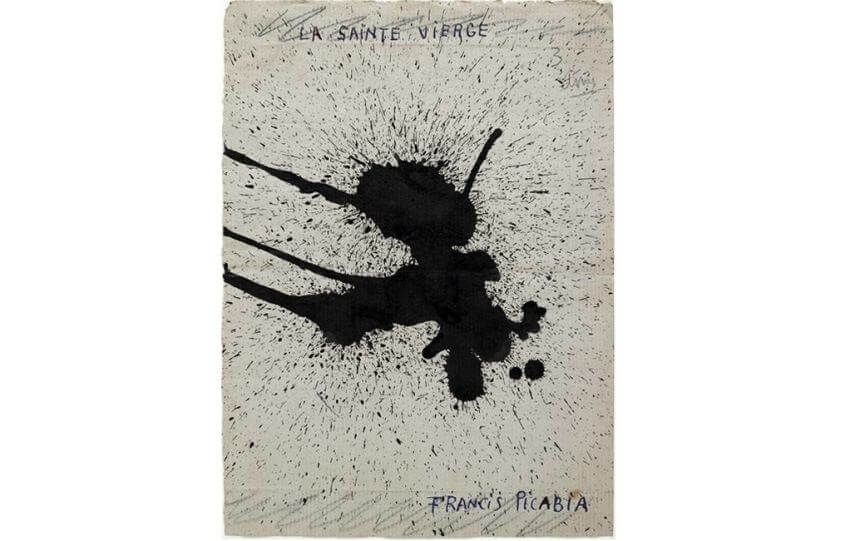

Francis Picabia - La Sainte Vierge (The Blessed Virgin), 1920. Ink and graphite on paper. 33 x 24 cm. Musée National d'Art Moderne, Paris

Hans Richter

Hans Richter was in his mid-20s when he first became exposed to Cubism in Berlin, at an exhibition at the gallery Der Sturm. After being drafted into the German Army in WWI, Richter was discharged following an injury. He promptly left Germany and moved to Zurich where he met the Dadaists. Richter’s experience in the war made him one of the most politically active members of the Dadaists. His paintings often portrayed horrific, macabre, though heavily abstracted imagery.

Hans Richter - Dada Kopf, 1918. Oil on canvas. 14.3 x 11.2 in

Richter’s tendency towards almost childlike gestures gives a sense of urgency and senselessness to some of his abstract works. He returns often to the theme of the “Dada Kopf,” or Dada Head. These sometimes-scrambled, sometimes-rigid images sublimely convey the Dadaist sense of the absurdity of human culture and logic.

Hans Richter - Portrait de Arp, 1918. Colored pencil on paper. 20.8 x 16.3 cm.

Destruction as Creation

The Dadaists found inherent insanity in the logic of human culture, including that of art, and yet they made art within the culture as a way of communicating their feelings. It is possible to argue that their anti-art was simply other art movement. But that would be to impose logic and rationale on something intended to exist outside of such ideas.

Abstract Dadaism paintings need not be appreciated on the level of their philosophical, or non-philosophical intentions. They can simply be appreciated for what they contributed to our understanding of our nature. By admiring their way of communicating feeling through abstraction we come closer to something beyond logic, something closer to nature, and something nearer the true value of art.

Featured Image: Francis Picabia - Totalisateur, 1922. Watercolor and ink on paperboard. 55 x 73 cm. Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía collection.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio