Why the Art Of Georg Baselitz Is Essentially Abstract ?

Feb 1, 2017

The art of Georg Baselitz has been called shocking, controversial and grotesque. It has also been called epic, and among the most internationally influential German art of the past 50 years. His paintings, sculptures and prints nearly always contain recognizable images from the objective world, however ambiguous they may be. And more often than not they overtly reference some political, historical or social subject mater. Nonetheless, despite its declarative, often straightforward nature, we consider the art of Georg Baselitz to be fundamentally abstract. To us there is clearly so much more to his work than its subject matter. Even Baselitz seems to not know exactly how deep the layers go. His works seem already to be in the process of asking what they are even before we have a chance to ask. To us they are more than images. They are the latest living records of an ongoing fight between the past and the present, meaning and nothingness, artist and art.

Talent Is Irrelevant

Georg Baselitz has described himself as being fundamentally hard to pin down. “I don't make it easy for people,” he has said. “Identification is difficult. One doesn't recognize my art right away.” Throughout his five-decade career, Baselitz has evolved through numerous different styles and explored various techniques. He recently even introduced what he calls remixes: quickly reworked updates of his own classic works. But one word suitably describes all of his work, regardless of its medium or its placement in time: brutish. A one-time contemporary of Baselitz, Jean-Michel Basquiat, once denounced critics of his own brutish style by saying, “Believe it or not, I can actually draw.” In the case of Baselitz, the brutish nature of his work makes us wonder: can he draw, too? For that matter, does he even want to?

Baselitz is considered sexist by many people for often saying that women make the worst painters because they care too much about virtuosity, and not enough about things like ambition, rebellion and aggression. Is he a secret virtuoso who simply chooses to make ambitious, rebellious, aggressively rough-hewn images because that makes him a better painter? Perhaps. But when Baselitz was in art school he was expelled his first year for being “socially and politically immature.” Maybe his brutish style is a necessity. Maybe it is not sexism that leads him to make those charges about women. Maybe it is just the mistake many successful people make by believing that since they are successful they must also be wise.

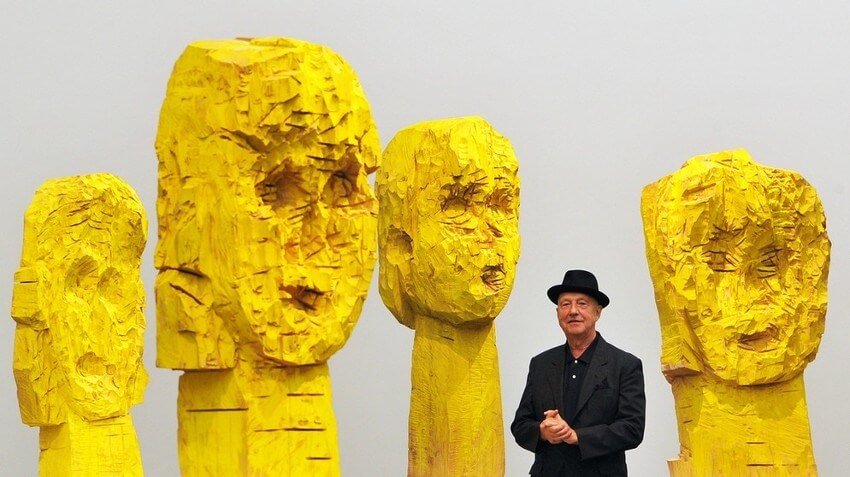

Georg Baselitz with his Dresdener Frauen (Dresden Women) sculptures, 1990. Wood carved with chainsaw. © Georg Baselitz

Georg Baselitz with his Dresdener Frauen (Dresden Women) sculptures, 1990. Wood carved with chainsaw. © Georg Baselitz

Image Is Nothing

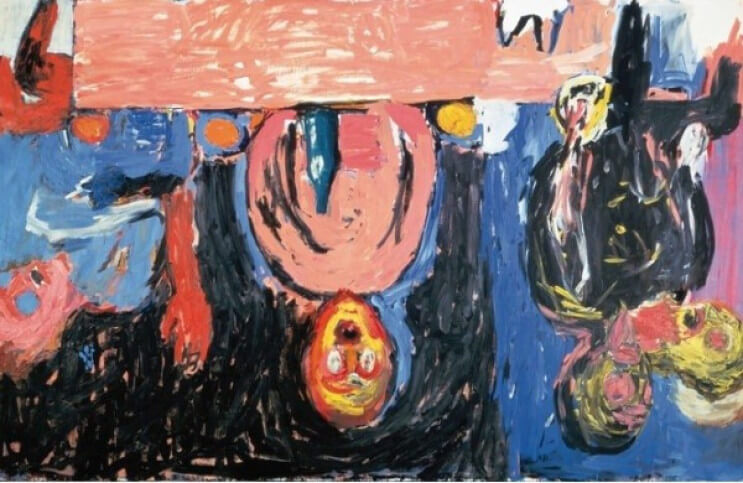

But even if his brutish style is by necessity instead of choice, we can still see in it the abstract signature of an artist striving for true expression. One of the works that first brought Baselitz into the public eye was a painting called Die grosse Nacht im Eimer or The Big Night Down the Drain. It depicts the tiny, warped, topless, childlike figure of a man dumbly standing with his pants unzipped wielding his enormous phallus. Soviet authorities in East Germany confiscated the painting as obscene when first exhibited, and many people have said it evokes the image of Adolph Hitler.

But The Big Night Down the Drain has also been called a self-portrait. To some it even resembles a Pinocchio doll with its nose ripped off and stuffed into his pants, perhaps a whimsical reference to the classic male lie. Whatever the true meaning, the color choices are dark and wild, his markings are alive, his compositional choices are playful, and the figure is both menacing and grotesque. All of these elements speak to existential ambitions, suggesting we should be guided more by those feelings than by the subject matter while interacting with the work.

Georg Baselitz - Die grosse Nacht im Eimer, 1963. Oil on canvas. Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany (right) and a remix of this painting from 2005 (right) © 2019 Georg Baselitz

Georg Baselitz - Die grosse Nacht im Eimer, 1963. Oil on canvas. Museum Ludwig, Cologne, Germany (right) and a remix of this painting from 2005 (right) © 2019 Georg Baselitz

Heroes Are Monsters

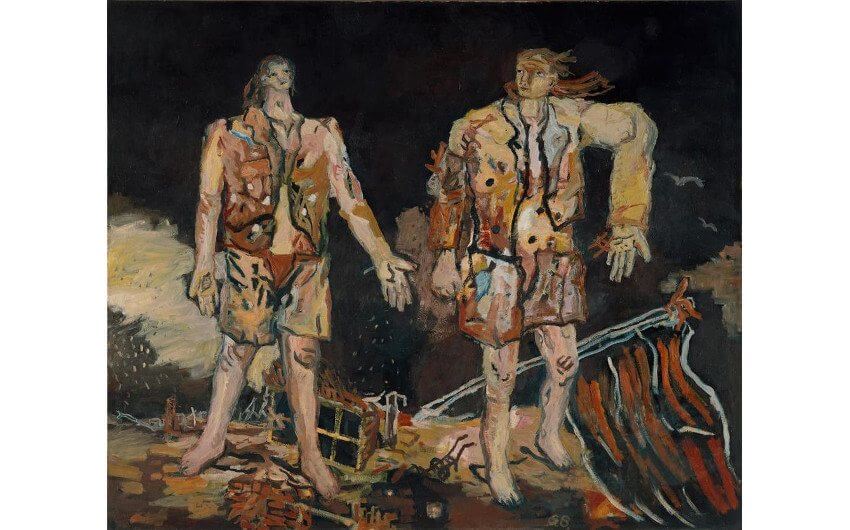

In the mid-1960s, Baselitz went to Florence and studied the paintings of Italian mannerist painters. Inspired by their dramatized physicality, he embarked on a major series of works presenting contemporary figures in similar mythic poses. These figures often resembled soldiers returning from war, or peasants wandering in apocalyptic landscapes. He referred to the paintings as New Types, and called the figures in them heroes, rebels and shepherds. The most famous example in the series is called The Great Friends. It depicts two such figures joining hands as they walk through a nightmarish void before a fallen American flag.

The New Types paintings seem undeniably narrative in their purpose. But it is difficult to explain what the narrative is. The facial mannerisms indeed recall heroic paintings of saints from the past. The hulking, mangled bodies evoke palpable strength, but have tiny heads. Are they commenting on the heroism of stupidity, the ignorance of war, or the necessity of being physically strong but mentally small if one wants to survive. Again, aside from the subject matter, abstract feelings of angst, meaninglessness and darkness are evoked by the color choices, the flatness of the picture plane, and the oddness of the composition.

Georg Baselitz - The Great Friends, 1965. Oil on canvas. 98 2/5 × 118 1/10 in. 250 × 300 cm. Städel Museum, Frankfurt © 2019 Georg Baselitz. Photo: Frank Oleski, Cologne

Georg Baselitz - The Great Friends, 1965. Oil on canvas. 98 2/5 × 118 1/10 in. 250 × 300 cm. Städel Museum, Frankfurt © 2019 Georg Baselitz. Photo: Frank Oleski, Cologne

The World Is Upside Down

In the midst of painting his New Types, Baselitz began fracturing some of his images, moving elements of the composition around in ways that made the subject matter more ambiguous and put more importance on the aesthetic component. The fracturing revealed an attraction Baselitz was having toward abstraction that found its full maturity in 1969, when he began painting his paintings upside down. To make his upside down paintings, he laid his canvases on the floor and painted them from an upside down perspective, and then hung them upside down on the wall when finished.

He remained dedicated to the importance of subject matter. For example, one of his most famous upside down paintings shows an image of an eagle, a possible reference to German history. He wanted the evocation that could occur when a viewer contemplated the subject of his works, but he also wanted the objectness of his paintings to be of primary concern. He wanted the paint to hold the attention of the viewer, thus objectifying the work, while retaining their symbolic potential. His upside paintings freed him from the trap of literal interpretation and helped him make works that could be considered purely as aesthetic objects.

Georg Baselitz - Portrat K. L. Rinn, 1969. Oil on canvas. 63 3/4 × 51 1/8 in. 161.9 × 129.9 cm (left) / Georg Baselitz - Finger Painting II Eagle, 1972. Oil on canvas (right) © 2019 Georg Baselitz

Georg Baselitz - Portrat K. L. Rinn, 1969. Oil on canvas. 63 3/4 × 51 1/8 in. 161.9 × 129.9 cm (left) / Georg Baselitz - Finger Painting II Eagle, 1972. Oil on canvas (right) © 2019 Georg Baselitz

The Brutality of Art

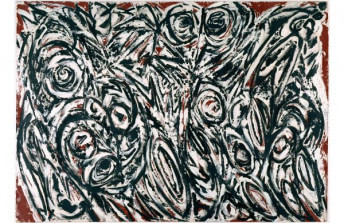

Often the work of Georg Baselitz has been contextualized by critics, historians and even Baselitz himself by referencing the German concept of Vergangenheitsbewältigung, which basically means wrestling with the past. It refers to the ways in which German artists after World War II have been forced to help explain the indefensible actions of their collective past. In an interview with Spiegel Online in 2013, Baselitz described his feelings about this concept, saying, “All German painters have a neurosis with Germany's past: war, the postwar period most of all, East Germany. I addressed all of this in a deep depression and under great pressure. My paintings are if you will.” Truly his paintings are battles. They are physical battles, in that he has never had an assistant despite the backbreaking difficulty of his process. And they are emotional battles, as he fights between his preexisting vision and the momentum towards something else that takes over once the painting has begun.

One of the most famous works Baselitz has made is, in fact, a reference to an actual battle. Titled ’45, its 20 panels elude to the bombing of Dresden in 1945. In it, Baselitz addresses brutality with brutality in a direct, personal way. He demonstrates that what is most important in order to create an acceptable future is not perfection, talent or grace. What is most important is the recognition of raw human desire. What is important is emotion, passion, and heart. And this work in particular also demonstrates effectively that for an artist, brutality is key: brutality toward the past, toward other artists, toward your own work, toward your subject matter, toward your medium. Regardless of its subject matter, every artwork Georg Baselitz has made is abstract because it shows us our world while simultaneously rejecting it, flipping it, and remaking it. It demands we see it but also that we look for something else, something different, something yet unimagined. It expresses dual realities: that within destruction is creation, within history is our future, and within every battle is something worth fighting for.

Featured image: Georg Baselitz - Dinner in Dresden (detail), 1983. Oil on canvas. © 2019 Georg Baselitz

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio