What's in The Miller Company Collection of Abstract Art ?

Mar 15, 2017

The Miller Company Collection of Abstract Art may be the most important collection of abstract art you never heard of. Ten years after its inception it changed its name to the Tremaine Collection, and 36 years after that it ceased to exist altogether in a unified form. Nonetheless, if you have been to any of the great modern art museums in the world, chances are you have seen at least one artwork that owes its provenance to this unrivaled collection. Its story begins in 1945, as the American abstract art market was in its infancy, and ends in 1991, when that same market was in the depths of its biggest depression. Yet the story is not about money. The couple that assembled the collection did so in earnest, out of adoration for art and respect for artists. At its height, it contained some of the most iconic works by the most important artists of the past century. Many were purchased directly from the artists in the early stages of their careers, for a pittance compared with their eventual value. And though ultimately the collection did fetch a fortune when auctioned, the full story of The Miller Collection of Abstract Art and its impact on the worlds of art, architecture, design, industry and culture is one of the great tales of utopian 20th Century ideals.

Meet the Tremaines

Shortly after the end of World War II, newly married New Englanders Burton and Emily Tremaine, residents of the small town of Meriden, Connecticut (population 40,000), shared a not-so-small dream. They imagined a thriving, intellectual world where art, design and industry partnered to create a more beautiful, useful and prosperous society. It was a dream partly inspired by the Bauhaus ideal of Gesamtkunstwerk: the total work of art. But whereas the Bauhaus imagined the coming together of creative disciplines like art, architecture, craft and design, the Tremaines dreamt of adding an additional element: industry.

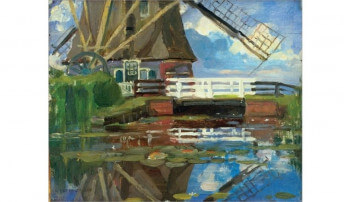

Burton was the owner and CEO of an industrial lighting manufacturer called the Miller Company, headquartered in Meriden. He and Emily were avid art collectors. They routinely visited artists in their studios and opened their house to artists on a social basis. They also believed abstract art held vital promise for the future of their industry. They saw clearly that abstract art had already served as inspiration for various forward-thinking architects around the world, and they imagined that trend would continue, and that industrial lighting solutions would play an important role.

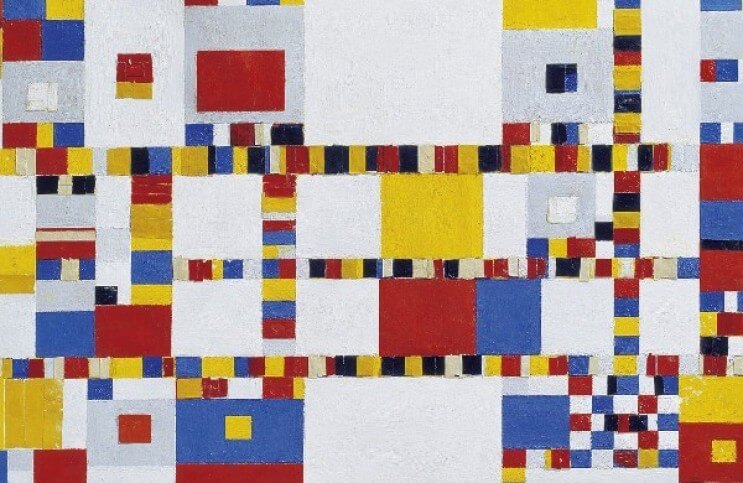

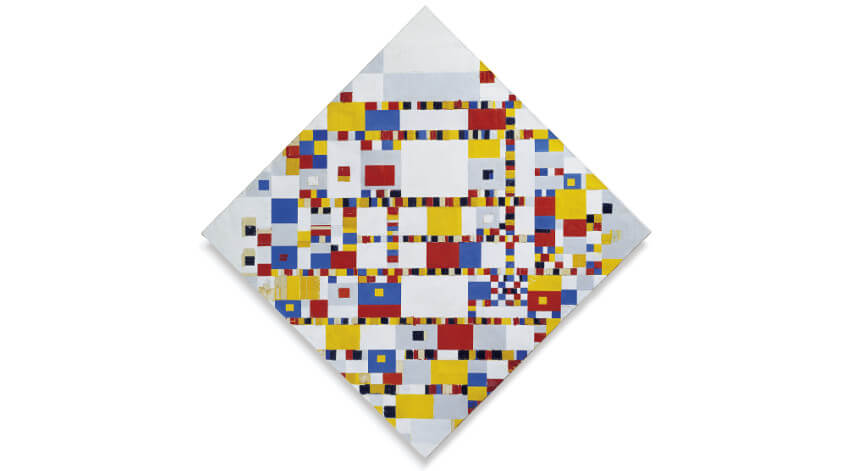

Piet Mondriaan - Victory Boogie Woogie (detail), 1942-1922, Oil and paper on canvas, 127 cm × 127 cm (50 in × 50 in), Gemeentemuseum, The Hague. Formerly owned by Samuel Irving Newhouse, Jr. and Emily and Burton Tremaine / The Miller Company Collection of Abstract Art, Meriden, CT

Piet Mondriaan - Victory Boogie Woogie (detail), 1942-1922, Oil and paper on canvas, 127 cm × 127 cm (50 in × 50 in), Gemeentemuseum, The Hague. Formerly owned by Samuel Irving Newhouse, Jr. and Emily and Burton Tremaine / The Miller Company Collection of Abstract Art, Meriden, CT

The New Medicis

The way Burton and Emily hoped to realize their dream was to use their corporate position to assemble a collection of art that could document the inspiration architects had already taken from abstract art. They then hoped to continue acquiring new works of abstract art that could serve as inspiration for future generations of architects. In the end they hoped those architects and designers who shared their vision would work with the Miller Company to create integrated lighting solutions for thoughtfully designed modern spaces and products.

But the Tremaines wanted more than just to sell lights. They looked back to the days when wealthy families paid artists and architects to create works that suited the needs and desires of the patrons. Who could argue but that this old system of patronage had the pleasant result of supporting the creation of many of the most precious ancient masterpieces we see today? The Tremaines envisioned a future in which industrial concerns like the Miller Company could be the 20th Century equivalent of the House of Medici: modern, industrial “families” that patronize artists and architects while also benefiting from their accomplishments and innovations.

Painting Toward Architecture

Burton Tremaine officially established The Miller Company Collection of Abstract Art in 1945. Emily had been collecting art for nearly a decade before she married Burton. The first painting she purchased, in 1936, was La Rose Noir, by Georges Braque. It joined the collection, as did one of the first pieces she and Burton acquired together: Broadway Boogie Woogie, by Piet Mondrian. With Emily at the helm of the collection, they acquired enough works in the first year to assemble a cohesive aesthetic position from which to communicate their vision of art, architecture and design working in concert with industry.

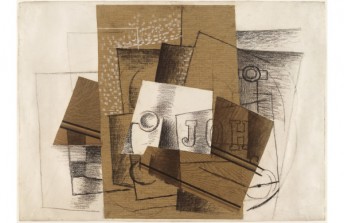

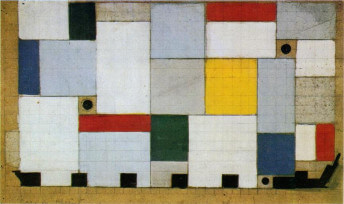

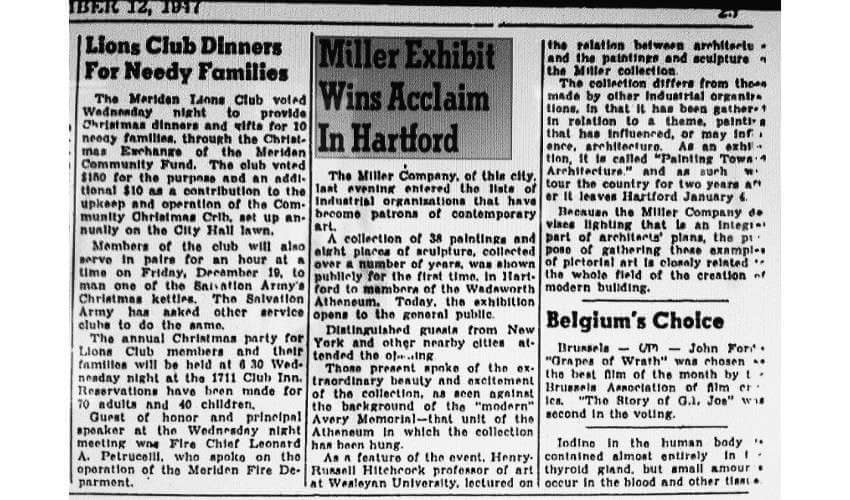

They held their first exhibition of the collection at the oldest continually operating public museum in the United States: Wadsworth Atheneum, in nearby Hartford, Connecticut. Titled Painting Toward Architecture, it featured 46 works representing those abstract artists the Tremaines believed most directly influential to modern architects and designers. In addition to Braque and Mondrian, works were on display by Wassily Kandinsky, Jose de Rivera, Pablo Picasso, Rufino Tamayo, Georgia O’Keeffe, Henry Moore, Ben Nicholson, Joan Miró, Roberto Mata, Fernand Léger, Paul Klee, Juan Gris, Perle Fine, Theo van Doesburg, Alexander Calder, Jean Arp, Ilya Bolotowsky, Josef Albers and many others.

Original local newspaper clipping from the 12 December 1947 debut of Painting Toward Architecture

Original local newspaper clipping from the 12 December 1947 debut of Painting Toward Architecture

The Tour

Following its Connecticut debut, Painting Toward Architecture traveled to 27 additional venues over a period of four and a half years. It opened in major museums like the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Walker Art Center, and the Milwaukee Art Museum, as well as many smaller institutions. Of particular interest to the Tremaines were university museums and galleries, where architecture and design students could be reached directly in hopes of inspiring the future generation.

After the first 11 exhibitions, the catalogue underwent an important evolution. The Tremaines added photographs and drawings of modern architecture, intended to drive home the point of the direct impact abstract art had made on architectural design. Among the buildings selected for this portion of the exhibition were the Ministry of Education building in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, designed by Le Corbusier, the Bauhaus in Dessau, Germany, designed by Walter Gropius, the Church of Saint Francis of Assisi in Pampulha, Brazil, designed by Oscar Niemeyer, and the Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht, Netherlands, designed by Gerrit Rietveld.

The Effects

Over the course of its tour, Painting Toward Architecture generated tremendous press, sparking a national, if not global conversation about the potential for art to inspire architecture and design. The Tremaines maximized the momentum by enlisting their favorite artists and architects to do work for the Miller Company. Emily Tremaine and Frank Lloyd Wright collaborated on a series of textile designs, and perhaps most strangely Josef Albers was hired to help design a new Miller Company logo.

But despite the success of its first exhibition, The Miller Company Collection of Abstract Art did not inspire the utopian ideal of industrial patronage the Tremaines envisioned, and in 1955, Burton signed the collection over to he and his wife, renaming it the Tremaine Collection. Nonetheless, the Tremaines remained as committed as ever to supporting abstract art. They continued growing their collection, eventually increasing it to more than 400 works. And they showed the collection twice more, in the 1984 exhibition The Spirit of Modernism, and the 1991 exhibition Delaunay to de Kooning: Modern Masters from the Tremaine Collection.

The Value of Success

The end of the story for the Tremaine Collection, a.k.a., The Miller Company Collection of Abstract Art, came on 12 November 1991 at 8pm. That is when Christie’s in New York began auctioning off the final remnants of the collection. Burton had died earlier in the year, and Emily had died in 1987. They had already given away numerous precious works to various institutions. More often though, Emily insisted the institutions paid a little something for the work, offering to sell it for a greatly diminished price then donating the remaining value. She believed when a museum paid for a work it was less likely to languish in storage.

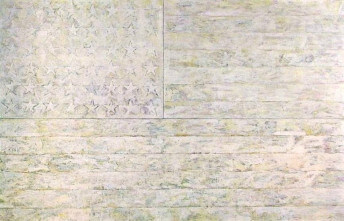

That was why the Tremaines did not donate the entire collection to a single institution. They bought the work because they enjoyed it. They wanted whoever ended up with it to enjoy it as well. They auctioned the work in hopes each piece would go to a single collector, someone who would love and care for it. The price they spent on the entire collection amounted to less than $5 Million. They made much of that back off a single painting, Three Flags by Jasper Johns, which they paid the artist $900 for in 1959 then sold in 1980 to the Whitney Museum in New York for $1 Million. But the value of their utopian dream to the history of abstract art, to modern architecture, and to the culture in general, is incalculable.

Featured image: Piet Mondriaan - Victory Boogie Woogie (detail), 1942-1922, Oil and paper on canvas, 127 cm × 127 cm (50 in × 50 in), Gemeentemuseum, The Hague. Formerly owned by Samuel Irving Newhouse, Jr. and Emily and Burton Tremaine / The Miller Company Collection of Abstract Art, Meriden, CT

By Phillip Barcio