Theo van Doesburg as De Stijl Ambassador

Some people believe in an ancient wisdom that predates, and will outlast humanity. Theosophists study such wisdom, searching for its manifestations and seeking ways of connecting it with their lives. Wassily Kandinsky and Theo van Doesburg, two of the earliest and most influential European abstract artists, both studied theosophy. Each wrote extensively about their search for an aesthetic style that could express the universal language of the soul. And although each of these artists were searching for a similar kind of discovery, the work they did took them down much different aesthetic paths. Wassily Kandinsky created an aesthetic language that was intuitive, complex and experimental. Theo van Doesburg focused more on paring his aesthetic language down, and focusing on simplicity and rules. Though Kandinsky avoided associating himself with any specific movement other than abstraction itself, van Doesburg was adamant about the style to which he was beholden. He was the proud founder and greatest global ambassador of De Stijl.

Birth of The Style

Three decades before Theo van Doesburg was born, the American author Henry David Thoreau wrote in his book Walden the famous advice to human beings to “Simplify, simplify.” The comic irony of this advice is that it could so easily have been simplified by cutting the second “simplify.” And hidden in that comedy are the seeds of the death of De Stijl.

“De Stijl” is Dutch for “The Style,” an art movement founded in 1917 that was predicated on the belief that in order to express the ultimate truths of the universe an artist must simplify. The two artists most commonly associated with De Stijl are Theo van Doesburg and Piet Mondrian. Both were staunch believers in the ability of geometric abstraction to become the ultimate expression of abstract simplicity. And both were close philosophical associates when they founded the magazine De Stijl in 1917 to promote their abstract geometric approach to art. But at that time they had not personally met. Having only exchanged letters, they did not yet realize that a hidden rift existed, a second “simplify” so to speak, which would eventually cause De Stijl to be ripped in two.

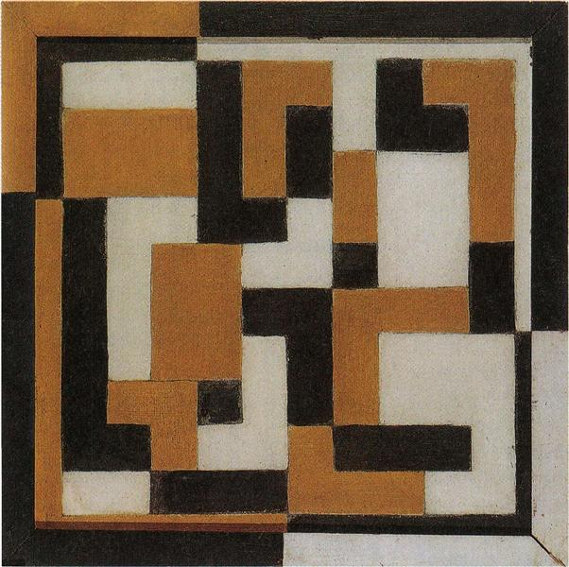

Theo van Doesburg - Composition, 1917. Oil on canvas. 27 x 27 cm. Private Collection

Spread of The Style

In the six years between the founding and the death of De Stijl, van Doesburg took it upon himself to be the global ambassador of his and Mondrian’s work. He was driven by the belief in the necessity of creating a total art, what is referred to as Gesamtkunstwerk. The basis of Gesamtkunstwerk is that art, architecture and design should work together in order to create a total aesthetic experience. Van Doesburg considered aesthetics to be the ultimate expression of spirituality. Rather than limit that expression to objects we look at, he believed it should manifest in a spatial, environmental way so that all aspects of daily life can be informed by aesthetic unity.

Van Doesburg expressed his search for Gesamtkunstwerk in numerous ways. The basic aesthetic approach of De Stijl incorporated lines, geometric shapes and a simple color palette. He used hat aesthetic to branch out into a number of fields. He developed designs for De Stijl buildings and furniture. He sketched plans for De Stijl-inspired interior environments. He wrote De Stijl-inspired poetry. He published and edited the De Stijl magazine, promoting it throughout Europe. He even invented a De Stijl typeface in which each letter consists of a square divided up into a grid of 25 smaller squares. (Today that typeface exists under the name Architype Van Doesburg.)

Theo van Doesburg - Counter composition X. 1924. Oil on canvas. 50.5 x 50.5 cm. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Theo Van Doesburg vs. the Bauhaus

Though his specific aesthetic was innovative, the concept of Gesamtkunstwerk, or a total art, was not unique to van Doesburg. In 1919 the German architect Walter Gropius opened a school in Weimer, Germany called the Bauhaus, which was devoted to the concept of developing a total approach to art that included the plastic arts, architecture and design. The Bauhaus was enormously influential and many of the greatest names in early Modernist art either studied or taught at the school.

In 1922, at the height of his enthusiasm, van Doesburg moved to Weimer and attempted to convince Gropius to let him teach his De Stijl principles at the Bauhaus. Gropius denied van Doesburg, allegedly due to the strict aesthetic limitations of De Stijl. Not to be discouraged, however, and convinced that his approach was equal to that being taught at the Bauhaus, van Doesburg opened his own school next door to the Bauhaus campus and successfully attracted a number of students who he taught the principles of De Stijl.

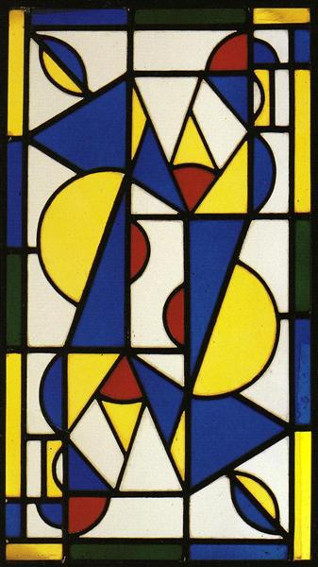

Theo van Doesburg - Dance I, c.1917. Doors-and-windows, designs-and-sketches, vitrages. Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

Van-Dada-Burg

According to all accounts, one of the most remarkable traits people admired about Theo van Doesburg was his sincerity. Like his contemporary Wassily Kandinsky, van Doesburg believed in the power of art to heal and transform the world. And it is precisely because of his legendary earnestness that it seems surprising that in addition to founding De Stijl, van Doesburg is also often closely associated with Dada. Unlike van Doesburg, Dada has a reputation of being cynical, sarcastic and anti-establishment. So why would someone who was committed to theosophy and academics associate himself with Dada?

Evidently the answer is because van Doesburg had a sense of humor. In the 1920s he served briefly as an editor with the Dada magazine Mecano. While working for the magazine, he also secretly submitted poetry to it under the pen name “I. K. Bonset.” Several of his poems were accepted and published in the journal, without any of his friends or colleagues knowing he had written them. His nom de plume seems to have been a twist of the phrase “Ik ben zot,” which roughly means, “I am foolish” in Dutch.

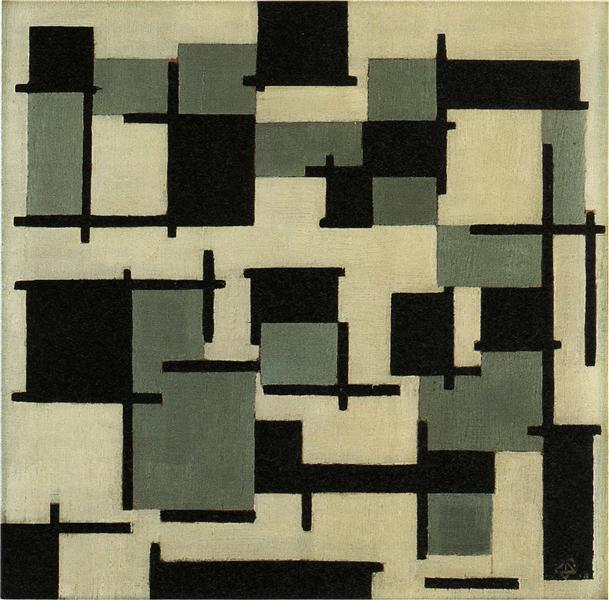

Theo van Doesburg - Composition XIII, 1918. Oil on canvas. 29 x 30 cm. Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Death of The Style

In 1923, van Doesburg moved to Paris specifically to be closer to Piet Mondrian so that the two of them could further their work on De Stijl. Almost immediately after he arrived in Paris, the two realized they had dramatically different personalities, as well as dramatically different visions of the direction De Stijl should take. They agreed that in order to express the ultimate purity of the universe, painting should be reduced to geometric abstract expressions of line, color and form. But Mondrian took that principle to the ultimate extreme. He only worked in horizontal and vertical lines, squares and rectangles, and the colors yellow, red blue, black, white and grey. In Walden-esque terms, his approach could be expressed as, “Simplify.”

But van Doesburg’s approach was more like, “Simplify, simplify.” He thought that limiting their lines to just horizontal and vertical was too limiting. He believed diagonal lines should also be used. But of course the addition of diagonal lines would also necessitate the allowance of a larger vocabulary of form, since diagonals naturally would result in triangles. Mondrian refused to accept such flamboyant ideas as diagonal lines and triangles, and he immediately disassociated himself from van Doesburg and De Stijl. Mondrian renamed his personal aesthetic approach Neoplasticism, and van Doesburg renamed his personal aesthetic approach Elementarism.

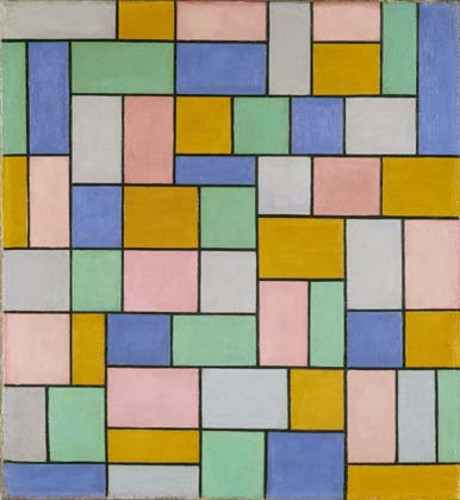

Theo van Doesburg - Composition in dissonances, 1919. Oil on canvas. 63.5 x 58.5 cm. Kunstmuseum Basel, Basel, Switzerland

The Style is Dead, Long Live the Style

It is strange to suggest we can discover reality by looking at pictures of it. We cannot learn about the essence of a forest from looking at a painting of a forest; we must go to the forest. That is what Theo van Doesburg was trying to express when he developed the aesthetic language expressed in De Stijl. He was convinced the deeper nature of reality could not be expressed by mimicry; it could only be expressed through abstraction. Though not alone in that belief, van Doesburg’s contribution was unique. Whereas some abstractionists advocated on behalf of one particular aspect of life, like the Futurists with speed, van Doesburg sought to express the totality of human experience. Whereas some advocated on behalf of chaos, van Doesburg stressed the importance of structure. Whereas some took structure to the most extreme limits, van Doesburg left room for a wider range of expression.

Most important of all to his legacy was the strength of the personal belief van Doesburg had in his own ideas. His ultimate expression of that belief was the home he designed and built for he and his wife Nelly. The home was entirely based on the De Stijl aesthetic and it incorporated his dedication to a total art that articulated his passion for Gesamtkunstwerk. Though he died before the house was complete, the building functions today in homage to his work, as an artist residency. Though he never lived within its walls, the house also functions as a unique and powerful testament to a rare artist. Van Doesburg dedicated his time, his vision and his fortune to creating an environment in which he and his wife could live out their daily lives surrounded by the aesthetic he helped create: a level of dedication few artists have the will or the skill to achieve.

Featured Image: Theo van Doesburg - Color design for the ceiling of the Cafe Brasserie

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio