The Abstract in Jasper Johns Artwork

Jasper Johns artwork can be understood as being abstract, although his approach is usually descibed as representational. The artist is usually associated with the The Walker Art Center in Minneapolis which has 434 Jasper Johns artworks in its permanent collection. Among them are several of Johns’ flag pieces. Upon seeing a single Johns flag, especially one that mimics the colors of the true flag, a viewer could easily take it at face value, interpreting it only as a picture of an American flag and nothing more. But seeing the pieces in multiple—one done entirely in silver, one featuring two flags side by side, one a screenprint, one that’s painterly, one that’s sculptural, and one that features the addition of a vase over the flag—the meaning of the flag as a symbol becomes less clear. This experience, of viewers questioning the meaning of a well-known symbol, is at the heart of abstract art, and of what Jasper Johns hoped his artwork would achieve.

Jasper Johns Artwork - Symbolic Representation

Johns painted his first Flag paintings in 1954, the same year the Army-McCarthy hearings were held in the US Senate. It was a time when every American was under pressure to declare their patriotism. The American flag was at the height of its objective meaning and its power as an aesthetic object. To those who loved America and saw the flag as something to be revered it could have been seen as blasphemy to paint an image of the flag, especially one that was incorrectly positioned. Or to those sympathetic to the citizens who were being harassed by the House Un-American Activities Committee, Johns’ flags could have been interpreted as a revolutionary political statement.

Johns made no explanation of the meaning of his flag paintings whatsoever. He simply appropriated the most potent symbol in the American visual lexicon and used it in his work. By painting it a variety of different ways and in a variety of different contexts he neutralized its inherent meaning and turned it into a symbolic form, no different than a triangle or a square. He proved that a white painting of an American flag form, such as his White Flag, painted in 1955, isn’t definitively an American flag any more than a silver circle over a horizon line is definitively the sun or the moon. Johns turned the flag into an abstract symbol devoid of intrinsic value and invited viewers to complete the flag artworks in their own minds.

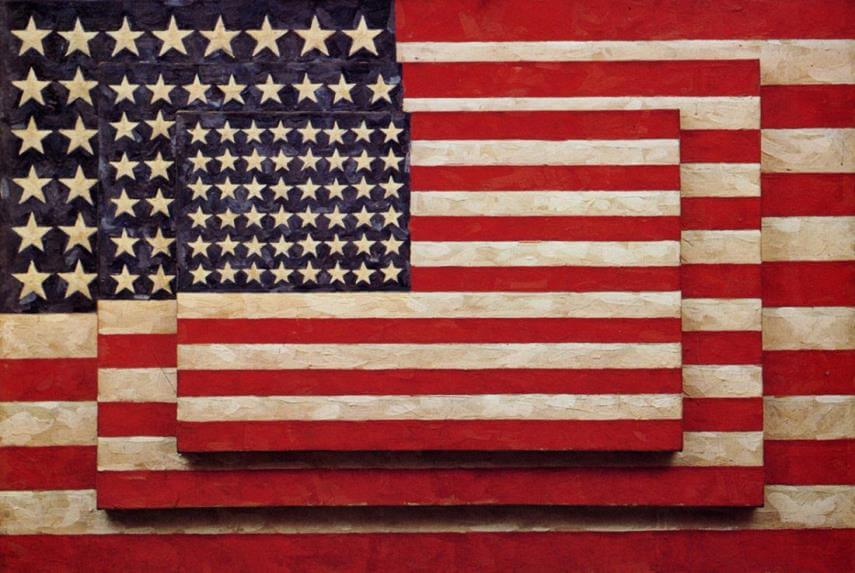

Jasper Johns - Flags I, 1973, Screenprint on paper, 27.375 × 35.5 in. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Material Contemplation

Johns’ method of painting added to the abstract symbolism of his flag paintings. Not only was he appropriating an image from the popular culture, he also constructed the image using a mixture of collage elements. He used shredded newspaper covered in encaustic as the foundation of the images, evoking Dadaist aesthetics and bringing into question whether the pieces were meant to be ironic or sincere. The collage elements introduced text and other imagery, utilizing them to culminate in a larger image. This raised the question of how the flag image could be more relevant to the meaning than the newsprint items. And what role did color play in the meaning? Is White Flag, for example, intended to suggest surrender?

The combination of all of these complimentary aesthetic choices forced viewers to contemplate Johns’ flags on a multitude of levels. On the surface, these works made the point that nothing has any meaning other than what we, as individuals, assign to it. On another level they asked profound questions about whether the established, communal meanings of symbols could be eliminated from the minds of people raised with them.

Jasper Johns - Three Flags, 1958, Encaustic on canvas, 30 7⁄8 × 45 1⁄2 in. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Semiotic Relationships

Semiotics is the study of symbols and their meaning. Integral to this branch of thought is the act of interpretation. When it comes to verbal languages, we see interpretation as an objective thing. To interpret a sentence from one verbal language to another requires that we all accept that each language has an objective basis of meaning. Jasper Johns turned the world of semiotics on its head. By appropriating imagery from the mass culture he began with symbols that were already familiar, or as he called them, “things the mind already knows.”

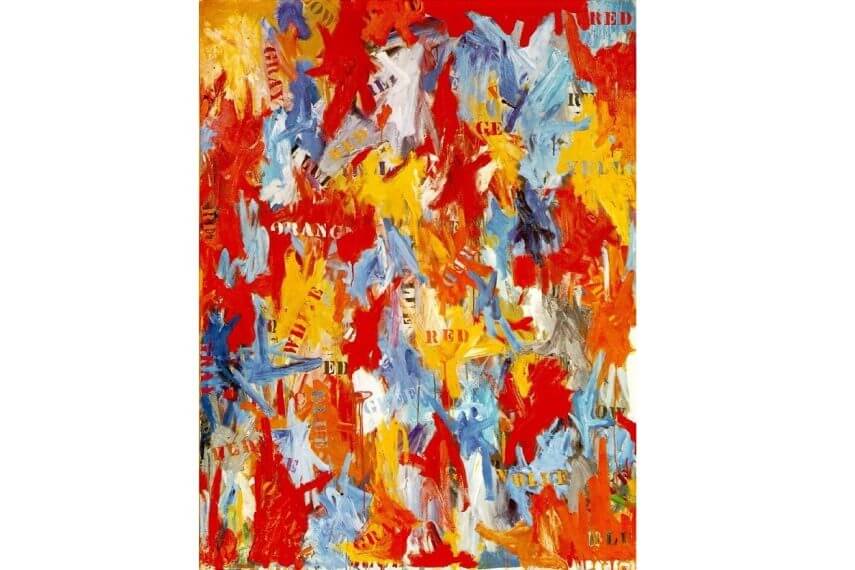

In his 1959 painting False Start, Johns incorporated the familiar symbols of the English language onto the surface. He inserted text related to colors but the words were painted in unrelated colors and were surrounded by other colors still. By divorcing these “things the mind already knows” from what the mind knows about them he destroyed the viewer’s ability to be an effective interpreter. Faced therefore with an inability to complete a quality interpretation of the symbols in the work, viewers were left with no choice but to either settle on an utterly personal interpretation, or to forego the interpretation entirely and simply relate to the painting as an object devoid of deeper meaning.

Jasper Johns - False Start, 1959, Oil on canvas, 67 x 54 in. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Context is Everything

Still active today at age 86, Johns has long gone out of his way not to explain the meaning of his works. Like many other artists he believes that the works rely on the viewer to complete them. One of the byproducts of this point of view is that Johns’ works have been a jumping off point for a number of artists who used them as the basis for other conceptual investigations. Johns’ appropriation of popular imagery directly influenced Pop Art. His semiotic obfuscation diverted attention away from subject matter, and toward formal qualities paintings have as objects, directly influencing Minimalism.

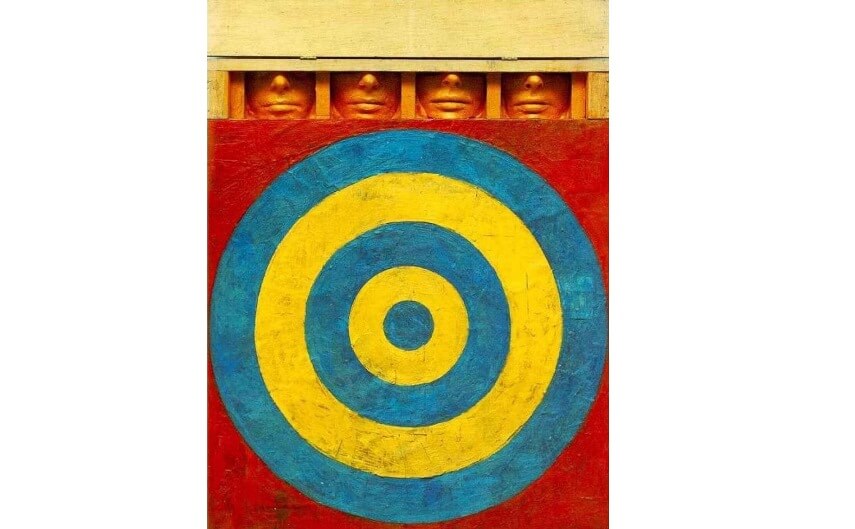

Johns also influenced the conversation Modernist Art has long had about the essential qualities intrinsic to various aesthetic phenomena. His work Target With Four Faces combines one of his iconic target paintings with four plaster casts of the lower half of a face mounted to the top of the work. Attached to the mounted faces is a hinged wooden slat that can be lowered in order to hide the faces from view. This piece firstly challenges the definitions of painting and sculpture. By also offering an interactive element, it becomes experiential and highlights the notion that each individual viewer is capable of experiencing something subjective from the piece and interpreting it in a personal way.

Jasper Johns - Target with Four Faces, 1955, Encaustic on newspaper and cloth over canvas surmounted by four tinted-plaster faces in wood box with hinged front, 33 5/8 x 26 x 3 in. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Facts and Fictions

Jasper Johns called his artworks “facts,” as in self-evident, indisputable things. Though he never clearly interpreted the meaning or purpose of his oeuvre, this pet name for his works perhaps gives the best hint to Johns’ mental state when it comes to his art. He obviously has a sense of humor. To call something a fact but then insist that it is open to interpretation is either comical or it’s absurd. If the works seemed at all cynical it would seem that Johns was trying to be absurd. But they don’t. They seem inquisitive. They seem open. They seem abstract. But they don’t seem sarcastic. It is for this reason that we can feel free to enjoy Johns’ abstractions with individual intellectual freedom. Through Jasper Johns’ facts we are free to invent our own fictions, and that is the greatest pleasure many of us receive from abstract art.

Futured Image: Jasper Johns - White Flag, 1955, Encaustic (wax), charcoal, fabric, oil paint, newsprint, 79 x 120 in. © Jasper Johns/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

All images of artworks used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio