10 Things You Didn't Know About Georges Braque

Georges Braque (1882-1963), often dubbed the founder of Cubism, was one of the most admired artists of his generation, earning praise from both the State and fellow artists. His name is rarely mentioned without reference to his contemporary, Picasso, however his contribution to Abstraction was equally remarkable and his personality more serene than that of his notorious friend and rival. We’ve compiled ten facts to give deeper insight into the artist’s life.

He failed the baccalauréat

Braque disliked school and was not an outstanding student. He said that “there was nothing remarkable about my early drawings [...] and even if there had been the teacher would have been quite incapable of realising it.” (Richardson, J., The Penguin Modern Painters) Braque trained to be a painter-decorator like his father which allowed him to experiment with the illusionistic-wood surfaces that characterise his work.

Braque’s father decorated the Caillebotte villa

The young Braque had many brushes with artistic greats: one of his earliest memories included watching his father decorate the villa belonging to Gustave Caillebotte. Braque and his father sketched together, copying illustrations from Gil Blas and taking midnight outings to the neighbouring sous-préfecture to retrieve posters by artists in the publication, notably Toulouse-Lautrec and Steinlen.

Matisse rejected Braque’s landscapes for the 1908 Salon d’Automne

Braque maintained that Matisse, on the judging panel for the Salon d’Automne in 1908, rejected a selection of Braque’s Cézannesque landscape paintings. One rumoured reason for Matisse’s decision is a bitterness he harboured because Braque had abandoned him for Picasso. Officially, the works were rejected because they were made of “little cubes”; marking the origins of ‘Cubism’.

Georges Braque - Studio V, 1949-50. Oil on canvas. 57 7/8 x 69 1/2" (147 x 176.5 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

He was awarded the Croix de Guerre and the Légion d’Honneur

Braque was called up in 1914 and the trenches had a marked effect on his artistic practice and his health. In 1915 he received a serious head wound that left him temporarily blind and required a trepanation to recover his eyesight. Invalided out of active service, Braque began practicing anew in 1916, this time informed by war. His artistic outlook changed when, in the trenches, his batman turned a bucket into a brazier, stabbing holes in it with a baronet, filling it with coke and setting it alight. The event stirred in Braque the realisation that everything is subject to metamorphosis and is changed according to circumstance.

Initially, Braque was not impressed by Picasso’s ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’

Braque did not immediately appreciate Picasso’s seminal work, but nonetheless the pair developed a close relationship. Introduced by Apollinaire, the artists explored the philosophies of Abstraction and in 1912 Braque experimented with cardboard and paper sculpture, earning the nickname ‘Wilbur Wright’ from Picasso. Both artists strived to eliminate the personal element from painting, refusing to sign their works and eliminating handwriting. Picasso accompanied Braque to the station when he left for war; however the relationship waned after Braque’s return and was never rekindled.

Braque kept a skull in his studio

Symbolising the anxiety caused by the dawning Second World War, the presence of skulls in Braque’s still lives can be seen from 1937. The artist appreciated the formal problems of mass and composition that the skull presented and it doubled-up as a makeshift palette, a duality the artist enjoyed. Whilst the skull is not seen anywhere else in the artist’s oeuvre, Braque had an enduring love for objects that came alive to the touch, hence the motif of musical instruments.

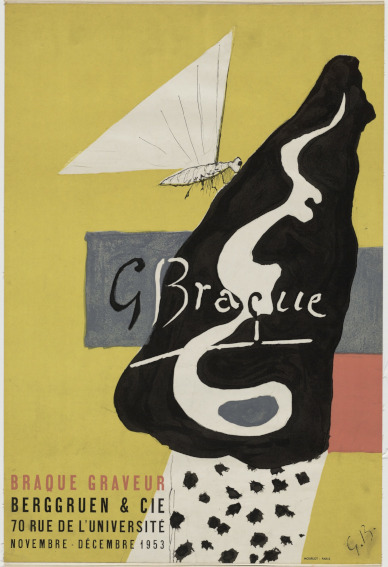

Georges Braque - G. Braque, Braque Graveur, Berggruen & Cie, 1953. Lithograph in six colors. 24 x 16 1/2" (60.9 x 41.9 cm). MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

Braque introduced Joan Miró to Aimé Maeght

During the Phoney War, Braque moved to Varengeville and invited Miró to stay. For Miró, this period was an influential one; Braque tutored the artist in poker and Miró learnt several techniques from Braque, namely the lost-wax process – for making carved metal sculpture – and covering canvases in a coat of white lead or casein. Miró and Maeght met in Varengeville and this introduction later proved fruitful.

He could leave a picture unfinished for decades

Braque left works like ‘Guéridon’ (started 1930 and completed 1952) for years before finishing them. This led to stylistic interruptions in his oeuvre, with some works displaying much earlier techniques interjected among his current production. Braque’s inimitable patience explains this practice, as the artist waited until the works revealed their identity.

Braque was the first living artist to have a solo exhibition at the Louvre

The artist was commissioned to paint three ceilings in the Etruscan room in the Louvre. The three panels show a large bird, a motif from the latter stages of Braque’s life. Braque thought the motif “universal”, allowing him to paint space while respecting two-dimensional constraints. In 1961, Braque was awarded a solo exhibition in the Louvre, L’Atelier de Braque.

Georges Braque - Guitar, 1913. Cut-and-pasted printed and painted paper, charcoal, pencil, and gouache on gessoed canvas. 39 1/4 x 25 5/8" (99.7 x 65.1 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (by exchange). MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris

He is buried in a cliff-top churchyard in Varengeville

Braque spent the last thirty years of his life in Varengeville (France) and his presence is marked by three stained-glass windows he designed for the chapel. Following a state funeral, Braque was buried in the graveyard at Varengeville alongside artists including Jean-Francis Auburtin and Paul Nelson. The cliff-top churchyard recedes by around a meter a year, despite numerous preventative attempts: like the remains it conceals, the cemetery is falling victim to the elements. A poignant end, perhaps, for an artist with an appreciation of metamorphosis and circumstance.

Featured image: Georges Braque - Still Life with Glass and Letters, 1914. Cut-and-pasted printed paper, charcoal, pastel, and pencil on paper. 20 1/8 x 28 1/8" (51.1 x 71.4 cm). The Joan and Lester Avnet Collection. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

All images used for illustrative purposes only