Jean Arp and the Abstraction Inspired by Nature

Occasionally our human egos convince us that we could save the world, if we just had the authority. Jean Arp, one of Dadaism’s founders, twice faced a world on the brink of annihilation thanks to megalomaniacs offering humanity safety or glory in exchange for power. Jean Arp’s artwork offered an alternative to such madness. It rejected the fatal logic that had led humans to believe they were above, in competition with, or somehow separate from nature. Jean Arp’s sculptures, paintings and collages demonstrated that humanity and nature are one. Through his artwork and his writing, Arp challenged the narcissism that had brought the human race twice to brink of self-destruction in the first two world wars, and brought to light insights that are particularly relevant today.

Jean Arp – Artwork and Revolution

When he was born, Arp’s hometown happened to be in desperate need of new art. Almost its entire collection had been destroyed just 16 years prior. Arp was born in Strasbourg, a multicultural melting pot and global crossroads since 12 BC, when the Romans founded the city. Today, Strasbourg is the peaceful seat of the European Parliament, but the city’s location on the border of France and Germany has placed it in the firing line in countless historic conflicts. In 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, Strasbourg’s museum of art was burned, along with the city’s library, which held many medieval and Renaissance relics. As a result of that conflict the city temporarily became part of the German Empire, until France reclaimed it at the Treaty of Versailles, and during that brief time of German control Jean Arp was born, to a German dad and a French mom.

Arp studied art in Paris, Munich and Weimar. By 1914, at the dawn of World War I, he had already exhibited his work with artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Henri Matisse. He had a global perspective, and a multi-cultural sensitivity. So it’s no surprise he preferred neutrality. When the German army attempted to force Arp into service, he faked insanity and absconded to Switzerland. There, in Zurich, he became a founding member of a cultural revolution designed to undermine the confused logic that had led the world to the edge of annihilation. That revolution was called Dadaism.

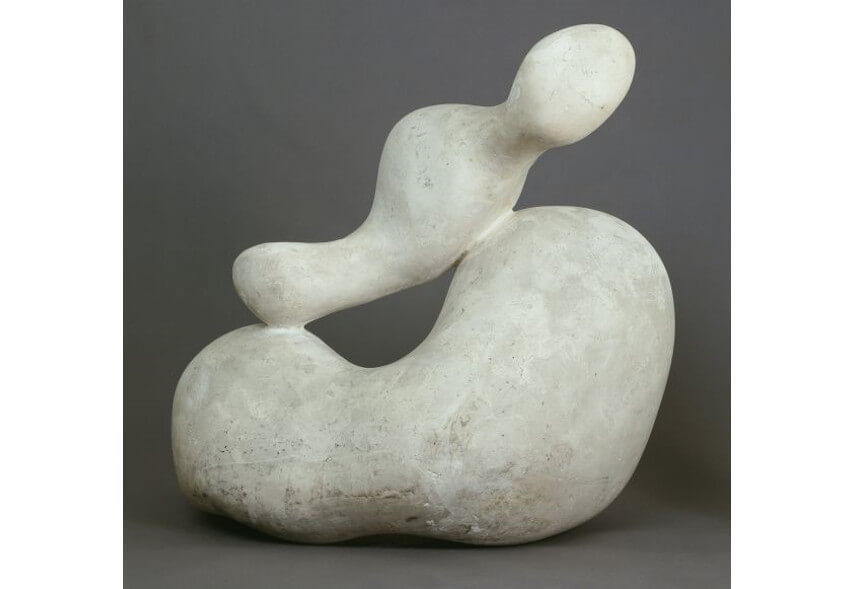

Jean Arp - Coryphee, 1961, 74 x 28 x 22 cm. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Arp - Coryphee, 1961, 74 x 28 x 22 cm. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The Nature of Chance

The Dadaists were disgusted by war’s madness. Their opinion was that the butchery they were witnessing could only have been caused by the enormous ego of humanity, which set its absurd logic above the natural world’s laws. During gatherings called Dada nights at Zurich’s Cabaret Voltaire, the artists in attendance experimented with new approaches to art that could undermine the existing cultural mentality. To that effect, the poet Tristan Tzara would tear up pieces of paper with words written on them and then string the words back together in a random way, making absurd poems from the chance linguistic assortments. Inspired by that technique, Jean Arp engaged in a similar experiment with images. He tore out shapes of paper and then let the shapes fall randomly onto a surface, pasting them where they landed and presenting the resulting image as his art.

Guided chance was at the heart of Arp’s Dadaist vision. He believed that society’s regulated, authoritative, historical reasoning was delusional, and that the natural world was governed by both logic and chaos. Said Arp, “Dada aimed to destroy the reasonable deceptions of man and recover the natural and unreasonable order.” As with all of Arp’s artworks, many people who encounter these collages made from chance arrangements of forms interpret them as abstract. But Arp insisted the images weren’t abstract. Rather, he considered them to simply be new. But they weren’t up for interpretation, and they weren’t altered from existing representational forms or compositions. They were fully formed and real, and so by definition, he called his art concrete.

Jean Arp - Collage with Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance, 1917, Torn-and-pasted paper and colored paper on colored paper, 48.5 x 34.6 cm. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Arp - Collage with Squares Arranged according to the Laws of Chance, 1917, Torn-and-pasted paper and colored paper on colored paper, 48.5 x 34.6 cm. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Concretion vs. Abstraction

Arp defined concretion as a process by which loose, unaffiliated fragments come together in order to form something solid, real and complete. Abstraction, on the other hand, refers to something that is not obviously complete but is rather based in the world of ideas, or is presented in such a way that it requires intellectual interpretation in order to be understood. Arp said his work did not require intellectual interpretation. His forms did not refer to other forms. They were new, but they were from nature, born from him in the same was as a tree bares fruit.

The reason Arp was so focused on the difference between abstraction and concretion was because he considered it to be at the heart of the human ego’s unreasonable desire to separate from nature. People wanted to look at something and understand it only in comparison to something they already knew. Arp wanted them to be open to new evolutions, to the unknown, as he believed that was the way of nature. He wrote, “I wanted to find another order, another value for man in nature. He should no longer be the measure of all things, nor should everything be compared with him, but, on the contrary, all things, and man as well, should be like nature, without measure.”

Jean Arp - Impish Fruit, 1943, Walnut, 298 x 210 x 28 mm. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Jean Arp - Impish Fruit, 1943, Walnut, 298 x 210 x 28 mm. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Biomorphism in Jean Arp Sculptures

As with his collages, paintings and reliefs, Arp’s sculptures were created with a focus on nature and chance. Arp always began his sculptural forms in plaster, which was pliable and easily susceptible to changes that might occur due to instinct, whim, or even by accident. He worked his sculptures intuitively into what he considered to be natural forms. The word most commonly used to describe Arp’s sculptures is biomorphic, meaning that they relate to the world of shapes associated with primordial nature. Another word commonly used to describe them is fecund, which refers to fertility.

His most powerful expressions of his belief in humanity’s connection to nature came in a series of sculptures he called Human Concretions. These forms were clearly not human figures, but they were biomorphic, fecund objects evocative of natural forces. They seemed alive. They expressed something akin to evolution, or growth. They were becoming something before the viewer’s eyes. That sense of process, of vitality, of never being caught up in the internal logic that demands that something is complete – that’s the logic of nature. These forms express Arp’s big idea, that although forms come together in concrete ways, they will soon enough change again, and nothing is ever finished.

One of Jean Arp’s Human Concretions, c.1935. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

One of Jean Arp’s Human Concretions, c.1935. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Contemporary Concrete Art

The artist André Breton, who founded Surrealism, once compared Jean Arp’s practice to the play of little kids searching beneath chestnut trees for the sprouts of new chestnut trees then transplanting them elsewhere so future kids might also marvel at new growth. Of his friend Arp, he said, “He found the most vital in himself in the secrets of this germinating life where the most minimal detail is of the greatest importance…”

Arp’s germinating principals indeed went on to influence generations of artists. He was a major conceptual influence on the British sculptor Barbara Hepworth, whose work we recently covered in depth here. Hepworth once commented following a visit to Arp’s studio that she saw the “movement in the forms,” and “began to imagine the earth rising and becoming human.” And Arp remains a powerful influence on today’s contemporary artists, such as the Swiss painter, sculptor and installation artist Daniel Göttin, who, like Arp, seeks to convey the clarity of concrete forms while also expressing and adapting to the changing nature of environmental factors.

Daniel Gottin - Hier da da dort, 2016, installation view

Daniel Gottin - Hier da da dort, 2016, installation view

A Lasting Legacy at Home

Reflecting back upon the age of Dada in the 1940s, Arp wrote, “While guns rumbled in the distance, we sang, painted, made collages and wrote poems with all our might. We were seeking an art based on fundamentals, to cure the madness of the age, and find a new order of things that would restore the balance between heaven and hell.” Despite the multitude of bombs dropped on its soil in the past 150 years, in the heart of Arp’s hometown of Strasbourg one very special building has survived: a 250+-year old building called the Aubette.

In 1926, as Strasbourg was still rebuilding following World War I, Arp was invited along with his wife Sophie Taeuber-Arp and the artist Theo van Doesburg, founder of De Stijl, to redecorate the Aubette. Recently, their work has been fully restored. It still stands up as a powerful contemporary testament to Arp’s ideas. And happily, from accounts written by those who knew him, Arp had a good sense of humor. Because after all the trouble he went to so his work wouldn’t be considered abstract, the Aubette has been given the nickname the Sistine Chapel of Abstract Art, something that would make him smile, naturally.

Featured image: Jean Arp - Araignee, 1960, 36 x 47 x 2 cm. © Jean Arp / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio