The Content and Emotion in the Art of Grace Hartigan

Feb 19, 2020

Grace Hartigan (1922 – 2008) has not been treated well by the self-appointed writers of art history. Throughout her career she was misunderstood and mislabeled, excluded from the movement she loved and lumped in with one she loathed. In spite of all that, or perhaps because of it, Hartigan is a wonderful role model—an artist who stayed true to her personal vision rather than conforming to the trends and expectations of the culture at large. Considered a “Second Generation Abstract Expressionist,” Hartigan was recently immortalized in the book 9th Street Women, by Mary Gabriel, which tells the story of five women—Hartigan, Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler—who were at the center of the New York School in the 1950s. Each of these five women developed a distinctive visual language that contributed significantly to the development and delineation of Abstract Expressionism. Yet, even amongst these pioneers, Hartigan was unique. Early in her career, her purely abstract paintings were recognized as extraordinary by museum curators like Alfred Barr and Dorothy Miller, who included Hartigan in several major exhibitions. Hartigan nonetheless began to feel as though something was missing from her abstract compositions. Right around the time when her career was taking off, and the famous art critic Clement Greenberg was getting to work touting her as one of the most talented abstractionists in America, Hartigan shifted ever so slightly away from pure abstraction. She started painting studies of the works of Old Masters and inserting figurative elements from contemporary life into her abstract compositions. To Hartigan, the blending of figuration and abstraction represented a more perfect mixture of content and emotion. “I have found my subject,” she proclaimed, “it concerns that which is vulgar and vital in American modern life, and the possibilities of its transcendence into the beautiful.” What was a breakthrough for Hartigan, however, was a letdown for Greenberg and the others who had once praised her abstract work, and they immediately abandoned their support. Hartigan nonetheless insisted on the primacy of her own vision. In the process, she may have severed her relationship with fame, celebrity, and patriarchal art history; but she proved truth and beauty can be found in resistance.

The Outsider Insider

Born to a poor, working class family in Newark, New Jersey, in 1922, Hartigan did not start out intending to become an artist. In fact, at age 19 she tried to abscond with her first husband to Alaska to become homesteaders. Even after she became a successful artist, she claimed never to have had any natural talent. “I just had genius,” she quipped. Her first professional artistic experience came during World War II, when she supported herself as a mechanical illustrator while her first husband fought in the war. In 1945, after being introduced to the work of Henri Matisse, she became inspired to pursue a career as a fine artist and relocated to the Lower East Side of New York City. There, Hartigan became part of a professional and social circle that included Abstract Expressionist pioneers such as Mark Rothko, Lee Krasner, and Adolph Gottlieb.

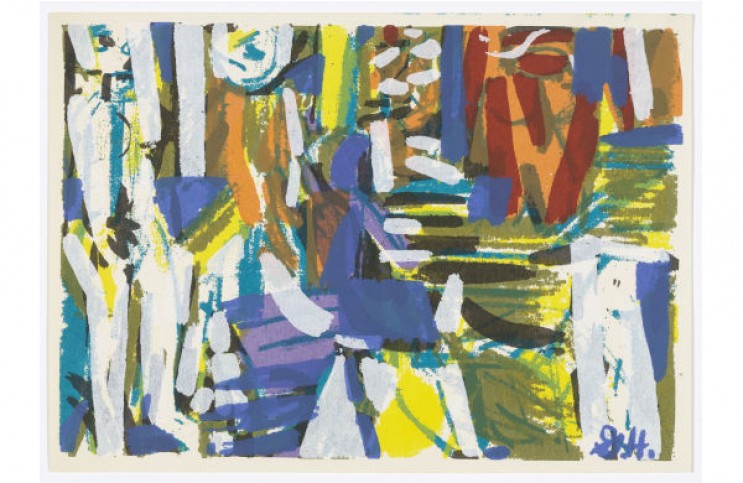

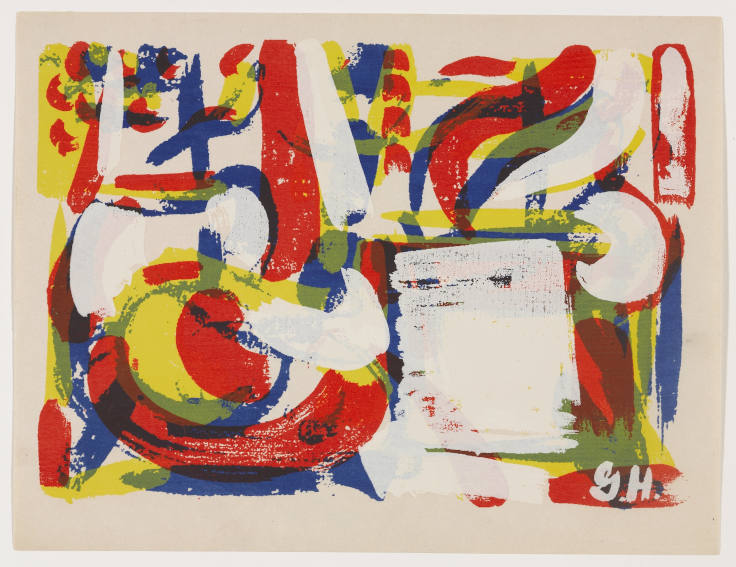

Grace Hartigan - Proof for Untitled from Folder, Vol. I, No. I, 1953. Screenprint. Composition (irreg.): 7 1/2 × 10 9/16" (19.1 × 26.8 cm); sheet: 8 11/16 × 11 5/16" (22 × 28.7 cm). Proof outside the edition of 500. MoMA Collection. Gift of Daisy Aldan. © 2019 Grace Hartigan

Grace Hartigan - Proof for Untitled from Folder, Vol. I, No. I, 1953. Screenprint. Composition (irreg.): 7 1/2 × 10 9/16" (19.1 × 26.8 cm); sheet: 8 11/16 × 11 5/16" (22 × 28.7 cm). Proof outside the edition of 500. MoMA Collection. Gift of Daisy Aldan. © 2019 Grace Hartigan

The intense, raw brush strokes and biomorphic forms in her early paintings reflect the interest she shared with those painters in both abstraction and the Surrealist technique of automatic drawing. However, Hartigan never completely fit in with her contemporaries. Aesthetically, she worried that she was borrowing too much from the ideas of others. Economically, she had to scavenge canvasses discarded by other artists and build stretcher bars from scrap wood. Socially, Hartigan felt like an outsider working among mostly male artists. She signed many of her early paintings using the name George Hartigan—a nod to 19th century female writers Mary Ann Evans, who went by the pen name George Eliot, and Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin, who used the pen name George Sand, reflecting the fact that she did not entirely feel accepted by the male-dominated New York School.

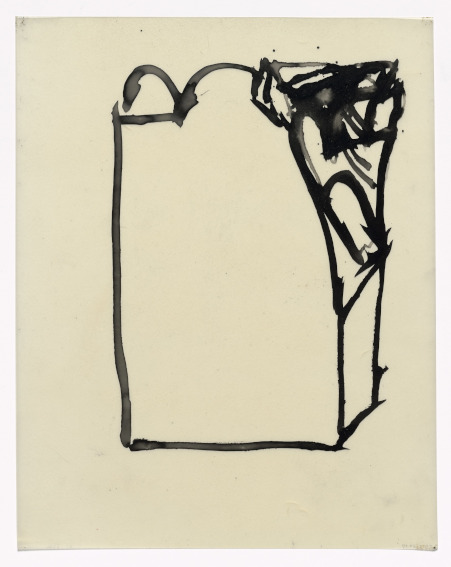

Grace Hartigan - Preparatory drawing for In Memory of My Feelings, 1967. Ink on acetate. 13 15/16 x 11" (35.4 x 28 cm). MoMA Collection. Gift of the artist. © 2019 Grace Hartigan

An Isolated Light

Perhaps her sense of herself as an outsider helped empower Hartigan to ignore the critics when they rejected her for introducing personal narrative content into her paintings. But there is no doubt that their misunderstanding of her evolution caused Hartigan to suffer. She once described her mature work as “emotional pain remembered in tranquility.” Ultimately, she rejected New York in return, moving to Baltimore where she spent four decades running the Hoffberger School of Painting, the graduate department of the Maryland Institute College of Art—a program founded for her and built around her teachings. Looking back, it seems absurd that critics would think that the addition of figurative references in her work excluded Hartigan from the legacy of Abstract Expressionism. The energy, intuition, and visceral materiality so essential to that movement never ceased to be evident in her work. It was also not like she totally abandoned abstraction; she just become convinced that her purely abstract paintings were missing something if they did not contain some recognizable reference to her real life.

Grace Hartigan - The Persian Jacket, 1952. Oil on canvas. 57 1/2 x 48" (146 x 121.9 cm). MoMA Collection. Gift of George Poindexter. © 2019 Grace Hartigan

The ultimate insult to Hartigan came late in her life, when a whole new generation of self-appointed art history writers dubiously re-framed her embrace of figuration as a landmark on the road to Pop Art, as if she had somehow inspired the rise of that movement. Hartigan deplored this association; to her, Pop Art represented only the fetishization of appearances, whereas her work was about communicating the underlying truth and emotion behind life. It would be far more accurate to call Hartigan a pioneer in Neo-Expressionism, with its raw, painterly attitude; or Feminist Art, considering the authoritative confidence with which she faced down the patriarchal misogyny of the art field. However, I think the best way to remember her legacy is to not burden her with any labels at all. Hartigan was unique. Her example proves that the best way to foster an inclusive, progressive, creative art field is not to get hung up on movements, but to embrace experimentation and welcome aesthetic deviation.

Featured image: Grace Hartigan - Untitled from Folder vol. I, no. I, 1953. Screenprint from a magazine with three screenprints. Composition (irreg.): 7 1/16 x 10 1/16" (17.9 x 25.5 cm); sheet: 7 7/16 x 10 7/16" (18.9 x 26.5 cm). Edition 500. MoMA Collection. © 2019 Grace Hartigan

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio