The Importance of Adolph Gottlieb's Burst series

Adolph Gottlieb once said, “The role of the artist, of course, has always been that of image-maker. Different times require different images.” Gottlieb witnessed multiple distinctly different times, and thrice significantly changed his method in order to respond to the evolution of culture. His oeuvre apexed with his Burst paintings, a series which he began in 1957 and continued to expand upon until his death in 1974. The visual language of the Bursts is simple and direct—the canvas is divided into two zones: top and bottom. The top zone is inhabited by one or more circular forms in a limited range of colors; the bottom zone is inhabited by a frenetic, gestural outburst of cacophonous, swirling energy, normally painted in black. For Gottlieb, the Burst paintings signified the ultimate expression of his big idea: that there are simultaneously existent polarities in the universe, such as darkness and light. Conventional wisdom tends to describe such forces as though they are dichotomous—as though light is fundamentally opposite of darkness. Gottlieb understood that light and darkness are points on a spectrum, and made of the same stuff dispersed in different measure. He considered polarities so similar that one can become the other with only the slightest nudge from the powers that be, and the two zones in his Burst paintings operate in a similar way. The circular forms seem to have it together, hovering confidently above what appears to be a fray. But both are part of the same picture, and neither is in a fixed state of being. What is up can come down, and what appears to be chaotic, under the proper circumstances, can coalesce and become one.

The Major Bursts

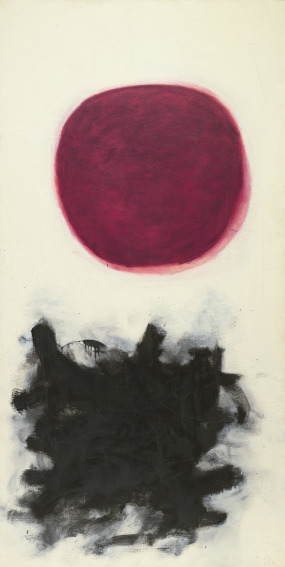

Examples of Burst paintings grace some of the most revered art collections in the world. The massive “Blast I” (1957), measuring 228.7 x 114.4 cm, hangs at MoMA in New York. On it, a gargantuan red orb stoically hovers above an equally menacing scrum of black, gestural marks. This iconic image kicked off the series, and a poetically charged revisitation of its iconography appeared again in 1973, just a year before Gottlieb died. In “Burst” (1973), one of the last paintings the artist created before he died, the red orb has softened and begun to disassemble, sending off pink sunbursts into the ether. Meanwhile, the chaotic scrum of gestural marks has broken apart into a sort of family of forms, sinking below the horizon line, seemingly emitting tendrils and seeds into space.

Adolph Gottlieb - Blast I, 1957. Oil on canvas. 7' 6" x 45 1/8" (228.7 x 114.4 cm). Philip Johnson Fund. © Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. MoMA Collection.

Among other famous Burst paintings is “Blues” (1962), now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Its blue and black palette is somber and serene, the darkness reading like an eclipse, or a solarized after image. “Trinity” (1962), another monumental Burst, hangs in the permanent collection of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. This 203.2 x 469.9 cm canvas extends the visual field horizontally. Three solid orbs—one blue, one red, and one black—float in space above an elegant assemblage of calligraphic brush marks. The marks seem to cast a grey shadow as a gentile yellow orb hovers in the middle-ground between the upper and lower zones. The range of variation exemplified by “Blues” and “Trinity” demonstrates the tremendous variation Gottlieb explored in his relatively simple theme, endowing each work in the Burst series with an idiosyncratic sense of meaning all its own.

Adolph Gottlieb-Icon, 1964. Oil on canvas. 144 x 100". ©Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation.

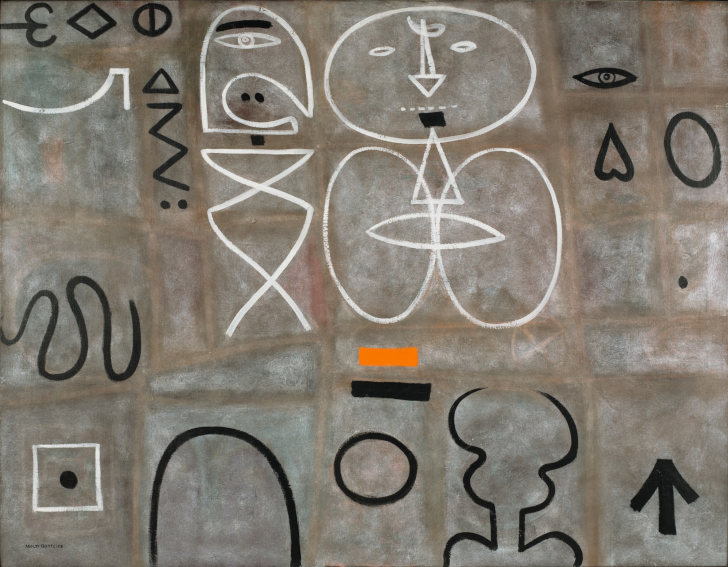

Preparing to Burst

Although he began painting in the 1920s, the journey Gottlieb took to arrive at the simple genius of his Burst paintings began in the 1930s. That is when he took to heart the Surrealist embrace of the subconscious. He came to the realization that the most essential aesthetic expressions are timeless because they relate to fundamental existential realities like power, fear, birth, and death: the stuff of myths. His research into this line of thinking led him to develop his first major series of paintings, which he called Pictographs. Based on a symbolic, intuitive language of abstract forms, his Pictographs were structured within grids—an attempt to convey compartmentalized expressions of reality. Though often considered abstract, Gottlieb described his Pictographs as realistic since they voiced the true, anxious, mysterious human condition. He painted them until 1951, when he decided the times called for something new. In search of a simplified method, he abandoned the grid and divided the canvas in two—a top and a bottom with a horizon line between them. He called this new series Imaginary Landscapes, because they conveyed the interior landscape of existence, including emotional, intellectual, intuitive, and subconscious states of being.

Adolph Gottlieb - Man Looking at Woman, 1949. Oil on canvas. 42 x 54" (106.6 x 137.1 cm). Gift of the artist. © Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. MoMA Collection.

The Burst series evolved out of the Imaginary Landscapes, and they represent the distillation of the same idea. Gottlieb simplified what was happening in the upper and lower parts of the Imaginary Landscapes, and stopped relying on an actual horizon line to divide the canvas into two parts. But the Burst paintings also represent an addition of sorts—the addition of space. Put in the simplest terms, Gottlieb realized that when the horizon line was taken away, the only thing between the upper and lower forms on the canvas was space, and the bigger the canvas, the more spread epic the forms, and the more space there appeared to be. But he did not think about space only in terms of distance that can be measured. It had more to do with the entirety of the visual and emotional world of the painting. The forms inhabit the same space, and yet occupy distinctive territories within the space. Their color space is distinct; their formal space is distinct; their linear space is unique; and their intellectual space is unique. Ultimately, this is the notion of space that was vital to how Gottlieb perceived his Burst paintings, because he understood it as a heightened expression of the totality of existence, and the myth of its seemingly individual parts.

Featured image: Adolph Gottlieb - Trinity, 1962. Oil on canvas. 80 x 185". ©Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio