The Spatial Reliefs of Hélio Oiticica

Dec 7, 2018

An exhibition of early works by Hélio Oiticica at Galerie Lelong & Co. New York is worth a trip to see, as it offers a glimpse into the pure plastic aestheticism that formed the basis of the oeuvre of this fascinating artist. As his career evolved, Oiticica was inspired less by formalism and more by sensuality and social interactions with audiences. The artist eventually became world renowned for works like his “Penetrables,” structures that viewers penetrate by walking inside them; his “parangolés,” wearable artworks that viewers could don while dancing; and his environments, such as the large-scale “Tropicália,” an island of sand and stone within the gallery on which multiple “Penetrables” are built to look like the favelas familiar to anyone who has visited the slums of Rio de Janeiro. All of these later works are based on the concept that the experiences members of the public have with art are more memorable and more vital if they are participatory. Yet the visual language that informs these participatory artworks is nonetheless rooted in something purely plastic. It emerged out of years of early research Oiticica conducted while striving to discover the essentials of his chosen medium. That research is the foundation of “Hélio Oiticica: Spatial Relief and Drawings, 1955–59” at Galerie Lelong. The exhibition presents three distinct bodies of work. First are examples from the “Grupo Frente” or “Front Group” series, gouache on cardboard compositions that sprang out of the remnants of the Concrete Art movement, as if examining what might be the fundamental visual structures of geometric abstract art. Next are several examples from the “Metaesquemas” or “Meta Schemes” series. In these gouache on cardboard paintings, Oiticica pares his visual language down to its simplest, most-self-referential elements—colorful boxes arranged in unconventional grids. Finally, the exhibition treats viewers to a work from the “Relevo Espacial” or Spatial Relief series. This series marked a pivotal moment when the forms and colors Oiticica had developed in his paintings jumped forth into dimensional space, becoming objects that cohabited with viewers in a zone of equal participation.

Rise of the Non-Object

Hélio Oiticica was born in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 1937. All the while he was growing up, a fierce optimism was spreading through the South American avant-garde. In Argentina, the Arte Concreto Invención would be founded in 1945 by artists who believed that the utopian, universalist ideas of Geometric Abstract Art could help transform the corrupted political system of their country. Meanwhile in Brazil, artists returning after being educated in Europe brought with them many of the same idealistic thoughts. They believed strongly that they could mobilize the formal philosophies of geometric abstract art to somehow transform traditional Brazilian society, leading to a more equitable, progressive culture. Their optimistic fervor found its fullest expression in the creation of the city of Brasília, the new, modern capital of Brazil—a futuristic metropolis of gleaming, white, Modernist architecture, master planned by the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer.

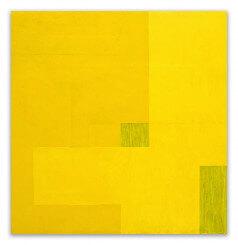

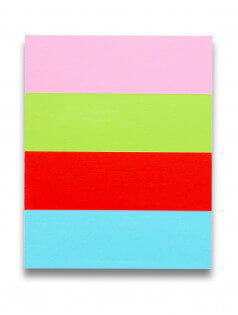

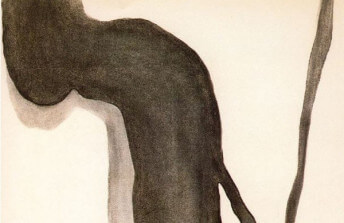

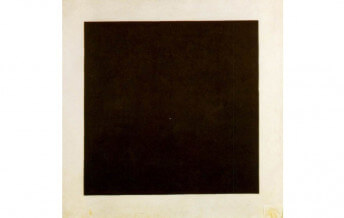

Hélio Oiticica: Spatial Relief and Drawings, 1955–59 at Galerie Lelong, 2018. Photo courtesy Galerie Lelong

Brasília was officially founded in 1960, but immediately the stark reality of its failure was evident to young artists like Oiticica. Although the expensive and beautiful buildings were glorious to behold, impoverished people and their children were still begging in the streets. The Concrete Art movement that had inspired this utopian vision to take root in Brazil turned out to be nothing more than the latest cultural perk of the elites. The disappointment of this era is what led Oiticica, along with Lygia Clark and Lygia Pape, to found the Neo-Concrete Movement. Their new movement was aimed at improving life for the ordinary citizens of Brazil. It was inspired by ideas expressed in an essay by Ferreira Gullar called “Theory of the Non-Object.” The essay postulated that material objects such as works of art are not in themselves valuable to human beings who search of meaning. They are only valuable in so far as their status as non-objects—material objects that allow “sensorial and mental experiences...to take place”—can be understood.

Hélio Oiticica: Spatial Relief and Drawings, 1955–59 at Galerie Lelong, 2018. Photo courtesy Galerie Lelong

A Restrained Hopefulness

By focusing on the creation of “non-objects” instead of traditional artworks, Oiticica and other Neo-Concrete artists hoped to inspire a new, if restrained hopefulness about the ways art could intersect with the needs and values of everyday people. Oiticica went out of his way to exhibit his works outside of museum settings. While he was alive, he only had one exhibition in a traditional museum. The rest were held in gallery spaces that were more casual, and less intimidating to viewers. He encouraged people to touch his works. Viewers danced and laughed while donning his “parangolés.” They congregated in his “Penetrables,” eating, drinking and even making love. But even this optimistic period soon came to an end for Oiticica. He moved to New York City and transformed his work once again, creating private environments inside of his own apartment where small groups of people would be invited for intimate experiences, during which they would do cocaine and watch video projections Oiticica had made.

Hélio Oiticica: Spatial Relief and Drawings, 1955–59 at Galerie Lelong, 2018. Photo courtesy Galerie Lelong

When Oiticica left New York and returned to Brazil, he was disenchanted by the extreme limits to which he had taken his concept. He stopped doing drugs and re-embraced formalism, as evidenced by late projects such as “Magic Square nº 3” (1979). Yet as this particular work also shows, Oiticica was still determined to create works that people could interact with and participate in. It is tempting to imagine what even greater works Oiticica would have achieved if he had not died in 1980 at age 42, from a stroke due to high blood pressure. The other great tragedy of his legacy is that in 2009 many of the works and personal effects Oiticica left behind were destroyed in a fire at the home of his brother. It is thus all the more precious to take advantage of any opportunity to see authentic examples of his work when they are on view. They are a glimpse into a brilliant mind that truly grasped the importance of the intersection between art and everyday life. “Hélio Oiticica: Spatial Relief and Drawings, 1955–59” at Galerie Lelong & Co. in New York is on view through 26 January 2019.

Featured image: Hélio Oiticica: Spatial Relief and Drawings, 1955–59 at Galerie Lelong, 2018. Photo courtesy Galerie Lelong

By Phillip Barcio

Featured Artists

Matthew Langley

1963

(USA)American

Tom McGlynn

1958

(USA)American

Jessica Snow

1964

(USA)American

Elizabeth Gourlay

1961

(USA)American