The Story of a Pioneer - Lygia Pape

On 23 March, 1959, an essay appeared in the Sunday supplement of the Newspaper of Brazil. It was signed by seven Brazilian artists, among them Lygia Pape. It spelled out in exacting detail what the artists were thinking about. Not that it explained their art, exactly. More like it explained their reasons for making art, and their hope for what their art might be able to achieve within society. Known as the Manifesto Neoconcreto (Neoconcrete Manifesto), the essay heralded a turning point in the history of Brazilian art. And with the benefit of hindsight we can now say definitively that it also marked a turning point in the history of 20th Century art in general. It concisely expressed many of the problems with the non-objective art forms that had emerged in the first half of the 20th Century, and proposed a number of ideas about how to overcome them in order to create a more constructive, open, and universal approach to abstract art. Of all of the artists who signed the Manifesto Neoconcreto, Lygia Pape went on to become the most influential. Her simple, elegant, precise method of working resulted in a body of work that continues to feel fresh and inspiring today.

Expression of the Problem

For anyone who does not understand why abstract art exists, or why it came about when it did or in the ways that it did, Brazil is an excellent point of reference. The rise of abstract art in Brazil came about for fairly easy to understand reasons. Brazilian history prior to 1945 is in many ways a story of exploitation, power struggles, and authoritarian control. Almost all art that Brazilian artists made prior to 1945 was figurative, much of it made directly in service to political agendas. It is easy to imagine that when, in 1945, the country experienced a wave of liberal reforms that accompanied a return to democratic rule, optimism and hope ran high in the minds of artists, who naturally believed they would finally have the freedom to develop a true Brazilian avant-garde. And just like with their European and American counterparts, that new freedom manifested quite naturally in a desire to make art that had no political or social narrative, and no sentimental context whatsoever.

It only makes sense. After being forced to paint murals of generals your whole life, you might naturally want to explore something different, right? For generations Brazilians had perceived of art only as a way to manipulate people. But the newly liberated artists of late-1940s Brazil were able to seek out new types of art that could be perceived as being totally neutral. The emerging Brazilian avant-garde found much inspiration from the wave of European abstract art that began showing in their museums. Of particular interest was Concrete Art. Named in 1930 by Theo van Doesburg, the essence of Concrete Art was to create artworks that reference nothing other than themselves. Concrete art avoids sentimentality, lyricism and images of nature, and tends to embrace objective geometric forms. In the opinion of many Brazilian artists in the late 1940s, Concrete Art philosophy perfectly expressed the problem: that their art had always been relegated to the expression of outside agendas. Through Concrete Art, they believed they could finally validate their work as having meaning and significance purely in its own right.

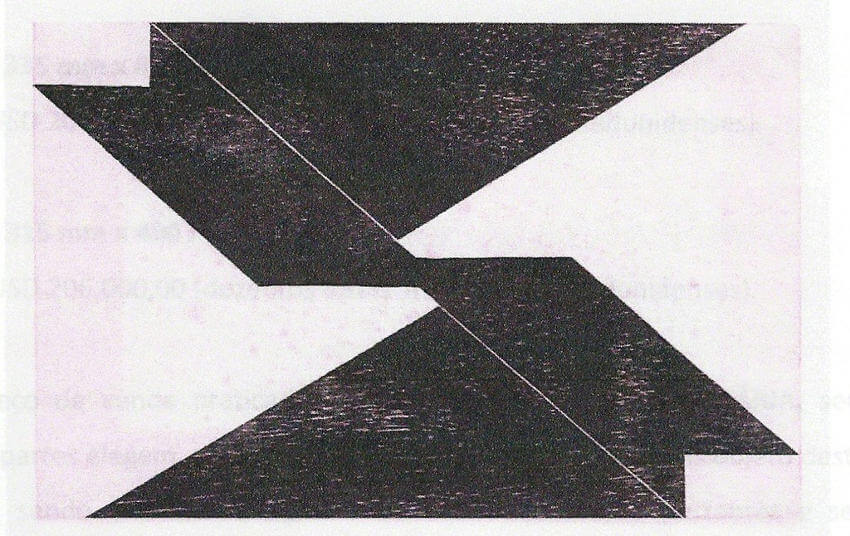

Lygia Pape - Sem título, 1959/1960, Xilogravura s/ papel japonês, 12 2/5 × 18 9/10 in, 31.5 × 48 cm, photo credits Arte 57, Sao Paulo

Lygia Pape - Sem título, 1959/1960, Xilogravura s/ papel japonês, 12 2/5 × 18 9/10 in, 31.5 × 48 cm, photo credits Arte 57, Sao Paulo

Confusing Existence with Science

Enter Lygia Pape. Born in 1927 in Rio de Janeiro, Pape was a young, enthusiastic artist who joined the emerging Brazilian Concrete Art movement in its earliest days, when she was just 20 years old. But after only a few years time, Pape and many of her contemporaries began to notice some problems with the purely rational, mechanical nature of European Concrete Art. They felt that in a way, it also served an agenda. It did not serve a specific political party, or a particular social point of view. Rather, it served the agenda of being completely disengaged from public life. It was not non-narrative. Rather it had an authoritarian narrative of neutrality.

So in 1952, Pape and several other artists, many of whom were students of the artist and educator Ivan Serpa, formed their own sub category of Concrete Art called the Grupo Frente (Front Group). The name referenced their opinion of themselves as the true Brazilian vanguard. They adopted the philosophical position that blindly following the existing theories of Concrete Art was a mistake. They believed that existence was sensorial and personal, and that personal experience should hold just as much value as scientific analyses in their work. They also embraced the value of experimentation. Though they still continued to make abstract work that was predominantly geometric, they believed that their work should be expressive and subjective, and therefore open to interpretation from spectators.

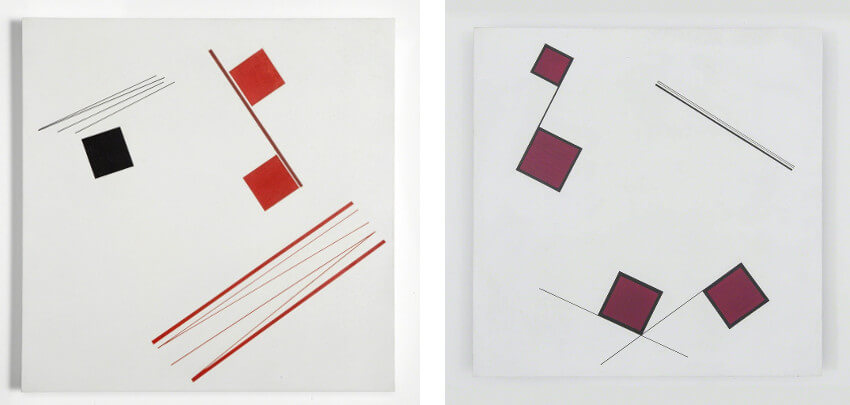

Lygia Pape - Grupo Frente Painting, 1954, Tempera on plywood, 15 7/10 × 15 7/10 × 1 2/5 in, 40 × 40 × 3.5 cm, photo credits Galeria Luisa Strina, São Paulo (Left) and Pintura (Grupo Frente), 1954-1956, Gouache sobre madeira, 15 7/10 × 15 7/10 in, 40 × 40 cm, photo credits Graça Brandão, Lisboa (Right)

Lygia Pape - Grupo Frente Painting, 1954, Tempera on plywood, 15 7/10 × 15 7/10 × 1 2/5 in, 40 × 40 × 3.5 cm, photo credits Galeria Luisa Strina, São Paulo (Left) and Pintura (Grupo Frente), 1954-1956, Gouache sobre madeira, 15 7/10 × 15 7/10 in, 40 × 40 cm, photo credits Graça Brandão, Lisboa (Right)

The Break

On the other side of this philosophical position was another group of Brazilian Concrete artists who called themselves Ruptura, or the Break. These artists embraced a purely unsentimental, objective, unemotional type of art more closely related to the European origins of Concrete Art. Arguments played out between members of these two groups for years, sometimes in person at exhibitions, other times in the press. But eventually, it became obvious that Ruptura held the philosophical high ground when it came to Concrete Art, since its origins were indeed unsentimental and purely objective.

It was because of this that in 1959 Lygia Pape and her colleagues founded the Neoconcrete Movement and published the Manifesto Neoconcreto. The essence of the Neoconcrete philosophy was that art objects are independent beings that are new to existence, that do not simply occupy space, but also actively participate in it. Furthermore, the meaning and relevance of art is not entirely known even by those who create it. Therefore, it is vital that spectators be able to participate in works of art so that through individual interpretations by viewers the work can fulfill its full range of potential meanings.

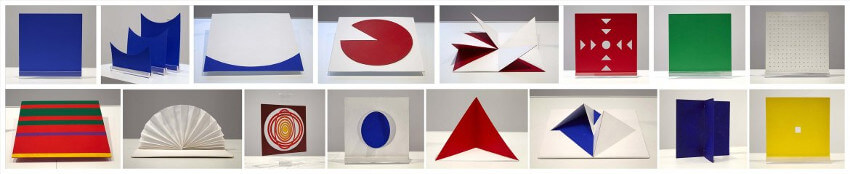

Lygia Pape - Livro da Criação (Book of Creation), 1959-60, Gouache and tempera on paperboard, 16-page popup book, 30.5 x 30.5 cm each, courtesy of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Lygia Pape - Livro da Criação (Book of Creation), 1959-60, Gouache and tempera on paperboard, 16-page popup book, 30.5 x 30.5 cm each, courtesy of the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía

Relationships in Space

Under the banner of the Neoconcrete Movement, Lygia Pape created artworks that allowed members of the public to experience art in a way they never had before. One of the first things she made was a 16-page popup “book” called the Book of Creation. It was not really a book so much as it was 16 separate geometric abstract objects painted in primary colors. The objects were meant to be handled and manipulated by viewers. Their kinetic, participatory nature was revolutionary. The Neoconcrete philosophy came through in the ability viewers had to interpret the geometric shapes any way they chose. Pape gave each “page” of the book its own name, which related to some moment in the history of life, such as the harnessing of fire, agriculture, or the discovery of navigation. But the shapes and colors were completely open to interpretation. Pape said she hoped each viewer, through their own experiences, would approach the book from a point of view “through which each structure can generate its own meaning.

Eight years later, in an even clearer elucidation of the Neoconcrete philosophy, Paper made one of her most whimsical creations: the Divisor. A massive, white cotton cloth in which scores of holes were cut, the work invited viewers to “wear” it by sticking their heads through the holes. Before being “worn,” the piece was a meaningless, white, geometric form. But when “worn” by spectators, it became a living thing. It connected the public to art in a literal way, and also connected them to each other. The visceral experience was in powerful, humorous, and aesthetically fascinating, and the philosophical implications were asserted in a playful way.

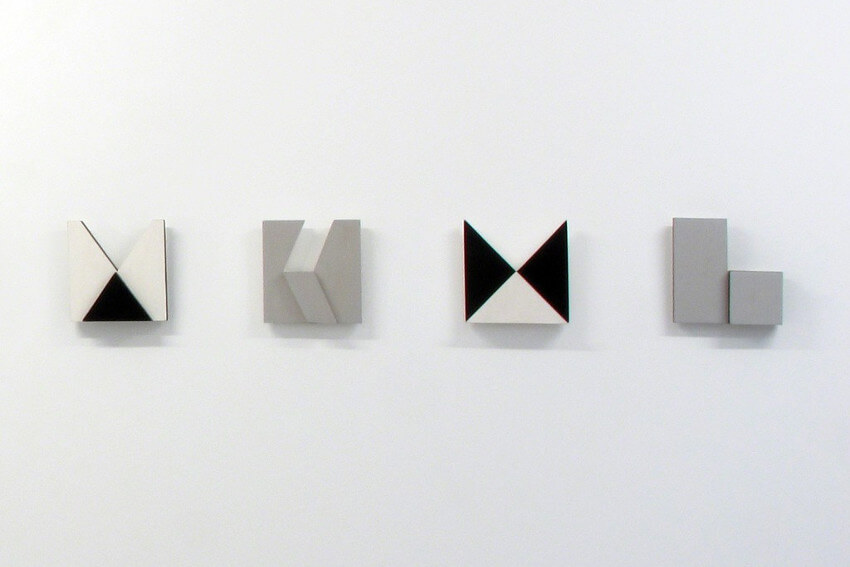

Lygia Pape - Livro Noite e Dia, 1963-1976 Têmpera sobre madeira, 6 3/10 × 6 3/10 × 3/5 in, 16 × 16 × 1.5 cm, photo credits Graça Brandão, Lisboa

Lygia Pape - Livro Noite e Dia, 1963-1976 Têmpera sobre madeira, 6 3/10 × 6 3/10 × 3/5 in, 16 × 16 × 1.5 cm, photo credits Graça Brandão, Lisboa

A Pioneering Legacy

Six years after the Manifesto Neoconcreto was published, Brazil again descended into military dictatorship. Lygia Pape continued to pursue her avant-garde, Neoconcrete vision, but her work pitted her against the government many times. She was even imprisoned and tortured for it. What her enemies did not realize is that by reacting in such a way to her work they only validated its inherent worth and its social and cultural power.

Today many of us take for granted that abstract art has the potential to express the various dualities we face, such as between our intellect and our animal nature, what we see and what we feel, and our physical existence and the possibility of the spirit. Lygia Pape was one of a handful of 20th Century artists who saw that potential early on. She had the artistic sensibility to grasp the inherent openness of geometric forms, and the humanity to grasp the need to stay open. That combination allowed her to create a legacy that continues to inspire artists and viewers today.

Featured image: Lygia Pape - Divisor, 1968, Cotton cloth, holes, 20m x 20m, © Projeto Lygia Pape

All images © Projeto Lygia Pape, all images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio