The Human Sculptures of Jonathan Borofsky

Jan 16, 2019

When he began his art career in the 1960s, Jonathan Borofsky aspired to find a way to unify Minimalism with Pop Art; to merge essentially abstract notions like purity and simplicity with a visual language that could hold mass appeal. Over the years, Borofsky transitioned through numerous distinct bodies of work in search of this elusive goal. One idea that he pursued related to numbers, which he feels have a sort of quasi-spiritual power: they connect people and places and things in concrete ways and determine every aspect of the physical and metaphysical realms. For years, Borofsky wrote down his growing count each day and made several artworks that simply stated the number he was on at a given moment. He signed other artworks that seemed to otherwise be unrelated to numbers not with his signature, but with his numerical tally from the day the work was finished. In addition to his number series, Borofsky created a body of work based on simple, text-based declarations made on two-dimensional surfaces, like signs. Another body of work recreated images and objects that Borofsky saw in his dreams. Each of these experiments touched variously on notions of abstraction and figuration. Each in its own way was both highly conceptual and utterly literal. Yet none truly achieved that for which he longed – an embodiment of Minimalism and Pop Art that could be instantaneously understood. Borofsky finally accomplished his goal by focusing on what is perhaps the most unassuming subject imaginable: the human form. Starting with small scale sculptures for galleries, moving up to complex installations featuring hundreds of human forms, then finally expanding into the public realm, Borofsky has created a massive body of human sculptures. Many of the viewers who encounter these sculptures read them as straightforward figurative works, and yet, in fulfillment of his ambition, many others also find in them qualities that reveal the ample and complex mysteries of the unseen world.

Material and Pictorial Essence

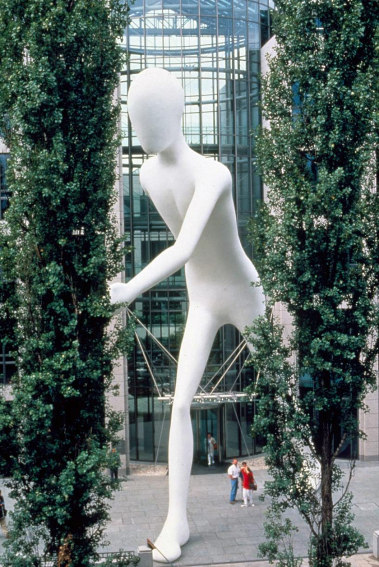

One of the most obvious ways Borofsky unified the methods of Minimalism with those of Pop Art is by endowing his human sculptures with a succinct material essence. Materials and processes are key aspects of the Minimalist ethos. Artists like Donald Judd prized industrial materials like metal, plastic and concrete for their impersonal qualities, which by their nature rejected virtuosity by disguising the “hand of the artist.” Industrial processes are also preferred by Minimalist artists because they democratize art. Instead of an artwork being idolized because of its rarity, it can be appreciated for the fact that it could be endlessly reproduced – a true reflection of the Modern Age. Along with the defeat of virtuosity and rarity, Minimalism also espouses simplicity, seeking to attain purity through the elimination of extraneous detail. Though his human sculptures take on a wide variety of physical and visual qualities, Borofsky always takes care to choose industrial materials and processes and to simplify his forms, ensuring the work express those three Minimalist ideals: democracy, abundance, and purity.

Jonathan Borofsky - Walking Man, 17 meters tall, steel inner structure with fiberglass outer shell. Permanent installation, Munich Re building, Munich, Germany, 1995. © Jonathan Borofsky

One essential difference between Pop Art and Minimalism is that Minimalist artists tend almost exclusively to make non-narrative, non-figurative work, while Pop Artists tend to do just the opposite, brazenly taking narrative, figurative content directly from popular culture. In the most general possible way, the human figure can be considered the ultimate example of appropriated cultural subject matter. But Borofsky does not stop there. For his human sculptures, he seeks out particular manifestations of the human figure that relate to popular culture in other ways, adding layers to the work that relate not only to humanity in general, but to specific human moments. Frequently, the most narrative elements in the work reveal the most hidden, and sometimes most cynical aspects of human nature. For example, a human sculpture he once installed in Los Angeles references athletes embracing after a game. Part of the “Molecule Men” series, the sculpture features hundreds of holes punched through the forms. One critic crassly interpreted it as a monument to drive by shootings, seeing the holes as bullet holes and assuming the darkened metal was a statement about race.

Jonathan Borofsky - People Tower. 20 meters tall, painted steel. Permanent installation, Olympic Park, Beijing, China, 2008. © Jonathan Borofsky

All About Relationships

In some respects with his human sculptures, it could be said that Borofsky is imitating, or at least striving to imitate, the whole range of human potentiality. Even when he singles out one specific human act, such as with his “Hammering Man” sculptures that show a person engaged in the everyday act of manual labor, he manages to evoke both extremes of the spectrum of human culture. In a material sense, the “Hammering Man” is extremely austere. In the sense of its scale and potential political ramifications, however, it is potentially ostentatious. By presenting the combination of both extremes within the container of the human figure, Borofsky invites viewers to speculate not only on what the sculpture is, but on what it is to them. This broad social statement echoes the words of Walt Whitman: “I contain multitudes.”

Jonathan Borofsky - Hammering Man, Seattle Art Museum. © Jonathan Borofsky

Most fascinating is how the elements that are the most abstract in the Human Sculptures often end up doing the most to affect the public narrative that evolves around the work. In the case of the previously mentioned Los Angeles sculpture, color and form – two of the most abstract elements of the piece – became more important than the true story behind the work. Meanwhile, other works, such as those in the “People Walking to the Sky” series, feature massive silver diagonal poles with small human forms walking upwards upon them. The narrative subject matter is easily relatable, but what gives the work its power and presence is its strong linear qualities and its metal finish. These aspects define the relationship of the work to the surrounding architecture. They also define its relationship to the viewers, as we realize that what we are really looking at is a reflection of ourselves. We are the ones traversing a footing that is easily described while marching happily into the unknown.

Featured image: Jonathan Borofsky - Human Structures and the Light of Consciousness. Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park - January 30 - May 10, 2009. © Jonathan Borofsky

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio