Minimalist Sculpture as the Pristine Contemplation of Space

Is Minimalist sculpture defined by a set of rules? Does a Minimalist sculpture’s success have to do with its own properties, or does it depend on how it interacts with its surroundings? The art critic Guillaume Apollinaire once declared that sculpture must represent forms from nature, or else it was architecture. The Minimalist artist Robert Morris described sculpture as occupying the middle part of a continuum of “useless three-dimensional things” ranging from monuments to ornaments. Comedic value aside, neither of these statements does much to help us understand the true, complete nature of sculpture, especially Minimalist sculpture. Rather than getting tripped up by academic definitions, we believe Minimalist sculpture can be best understood by keeping an open mind and by looking carefully at the artists who pioneered its ways.

Minimalist Sculpture’s Founding Father

Ronald Bladen demonstrated exemplary skill at drawing and painting from an early age. But his sculptural works are what brought him fame and respect. In the early 1960’s Bladen shifted his practice away from the abstract expressionist paintings he was making and started crafting large-scale wooden objects. Some forms were recognizable, like a giant X, and others were abstract. He didn’t specify precisely what the objects were, he simply pointed out that he was trying to make something that had “presence.”

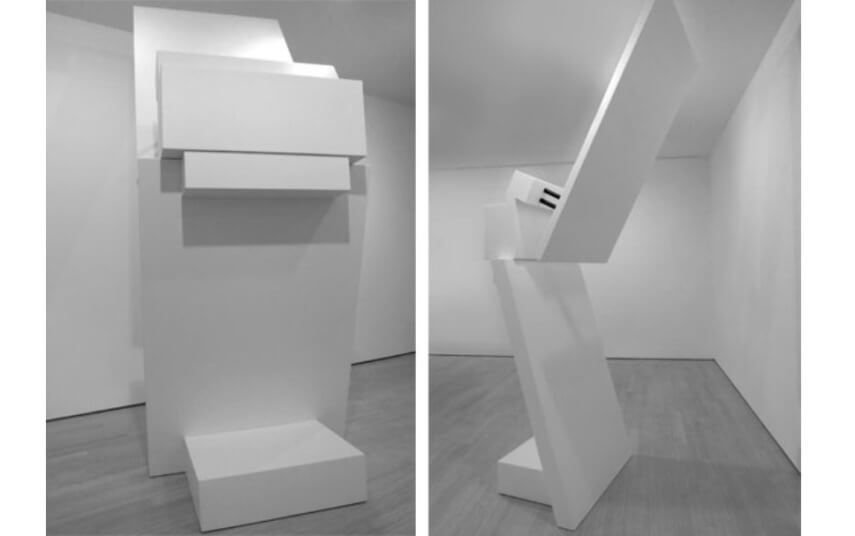

One of Bladen’s earliest minimalist sculptures works was called White Z. It was neither geometric nor figurative. It was abstract, monochromatic, hard-edged and intricate. It reacted to light, was tactile and sat on the floor. It was not reduced from a larger form but rather was constructed from smaller forms. It possessed its own gestalt: an organized whole that became more substantial than the sum of its parts.

Ronald Bladen - White Z, 1964, © The Ronald Bladen Estate

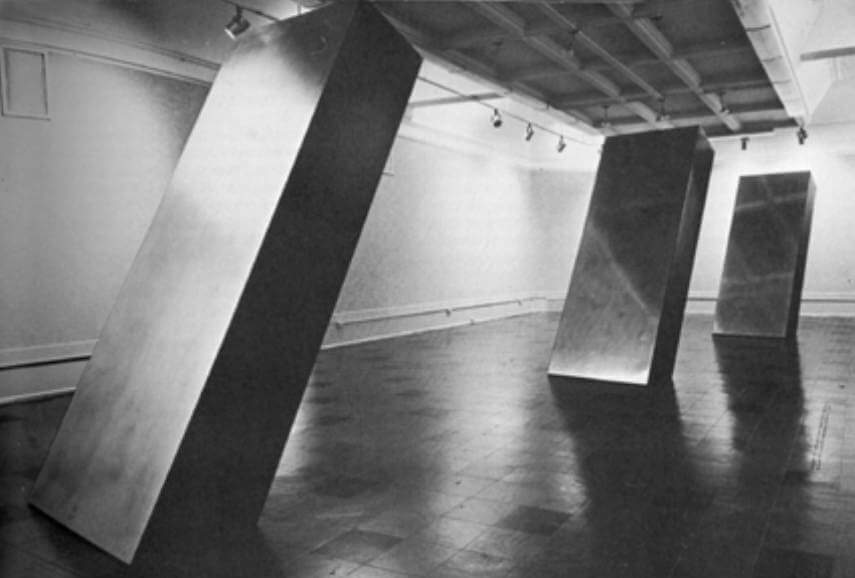

In 1966, Bladen’s work was included in the exhibition Primary Structures, along with Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Dan Flavin, Carl Andre and dozens of other Minimalist artists. That exhibition is considered to have represented a defining moment in the history of Minimalism. Bladen had one work in the show, a three-piece sculpture titled Three Elements.

The work was almost monumental in scale. It transformed the very nature of the space it occupied. Space is just an area within which stuff exists and moves. Three Elements created new spaces within a space. It became space. It forced contemplation not only of its own shape but also of the shape of its environment and the other inhabitants of its surroundings.

Ronald Bladen - Three Elements, 1965, © The Ronald Bladen Estate

Sculptural Values

Despite the undeniable “something-ness” of Bladen’s sculptures, some critics and viewers at the time, and some artists as well, didn’t think of them as sculptures. The existing definitions of sculpture seemed not to apply to whatever these things were. That’s precisely why these works were so revolutionary, and so perfectly suited to the emerging Minimalist theory of the time. They required a paring down of the very definitions of art.

Rather than defining a sculpture as something figurative, or geometric, or something carved from some material or something cast from some other material, these objects required a different explanation. They redefined sculpture as something characterized not according to what it is, but according to what it isn’t. A painting is an aesthetic object that consists of a surface acting as a support for paint, the purpose of which is contained in or communicated through the paint on the surface. Architecture is a structure intended for habitation. A sculpture is neither. It’s an aesthetic object that’s not a painting and isn’t architecture but that exists in three-dimensional space.

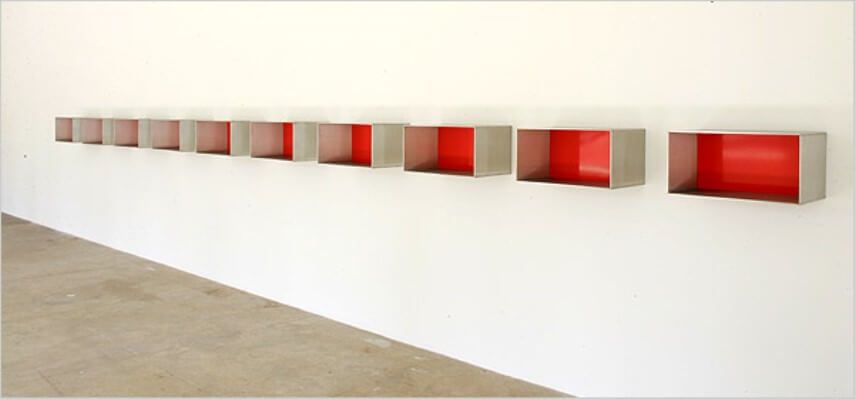

Donald Judd - Untitled specific objects, © Donald Judd

Sculpture’s Relationship to the Wall

One of the greatest challenges Minimalism posed to sculpture was whether sculpture had to be placed on the ground. Robert Morris once declared that sculptures absolutely had to placed on the ground, for only on the ground could they be affected by gravity, an essential sculptural property. But some of the most famous sculptural objects created by artists associated with Minimalism do in fact hang on the wall, or otherwise utilize the wall for support.

Donald Judd called the sculptural works he created Specific Objects. He defined them as neither paintings nor sculptures. Many of his most famous Specific Objects hang on the wall. They’re three-dimensional objects, they have a definite shape, they possess scale, they interact with light and they are tactile. They possess color and surface, as all material things do, but their purpose is not defined by those elements nor is anything necessarily communicated through them.

Are they sculptures or are they not? Whatever semantic games we wish to play, Judd’s works are clearly sculptural in nature. But by hanging them on the wall new questions were posed about spatial relationships. Rather than using the space of a gallery to contextualize works of art, these works of art re-contextualized the spaces in which they were installed. They both inhabited the environment and re-ordered it. They asked viewers to contemplate the additional spaces the parts of the works created through their presence. They even questioned the role of the architecture by attaching themselves to it. Though not forced to the ground by gravity, they drew attention to gravity by demonstrating resistance to it.

Ellsworth Kelly - Work, © Ellsworth Kelly

Ellsworth Kelly - Work, © Ellsworth Kelly

The Shape of Change

The works of other Minimalist artists such as Ellsworth Kelly and John McCracken also challenged existing definitions of sculpture. Kelly’s shaped, monochromatic surfaces hung on the wall and were covered in paint, but were far more aligned with the essence of sculpture than that of painting. McCracken’s monochromatic “planks” rested against the wall, using it for support as a painting might, but foremost relying on the floor.

Though each of these Minimalist artists went to some effort to define what they were doing and to address the debate about how to define their sculptural artworks, there remains much room for continued debate on the topic. The contemporary Minimalist artist Daniel Göttin is one of many artists who continue to explore this loosely defined aesthetic zone. A multi-disciplinary artist, Göttin creates murals, installations and geometric, three-dimensional abstract objects that hang on the wall.

His wall objects possess surfaces that are either painted or covered in other industrial mediums, but they’re not defined by their painted surfaces, and the surfaces communicate nothing specific. They’re sculptural, yet they hang flat to the wall. Behind them and within them space is created and redefined, and our experience of the surrounding space is re-contextualized by their presence.

John McCracken - work, © John McCracken

John McCracken - work, © John McCracken

Simplicity Isn’t Simple

One of the key lessons Minimalist sculpture teaches us is that the semantics of labeling is irrelevant. The meaning we find in these works comes less from what we call them and more from the ways in which they invite us to contemplate space. Through them we return to the purity of this simple revelation, that they, like we, inhabit space, disrupt space, contain space, define space, contextualize space and bring order to space.

Despite their simplicity, they’re infinitely complex in their ability to challenge and engage us. As Robert Morris pointed out, “Simplicity of shape does not necessarily equate with simplicity of experience.”

Featured Image: Daniel Göttin - Untitled E, 2005, Aluminum foil on corrugated cardboard, 25 x 25 in.

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio