The Exciting Revolution of Louise Fishman

Sep 22, 2017

Louise Fishman has been called a revolutionary before. It is a label that has been hurled at her countless times for reasons that have little to do with her, and a lot to do with a culture that feels compelled to compartmentalize people who threaten the status quo. But the politics of social protest aside, Fishman has accomplished something truly revolutionary over the course of an art career that has so far spanned six decades: she has expressed herself honestly in her art. How is that revolutionary? Honest self-expression may sound like a simple, easy thing to achieve. But it is much more difficult than it sounds. To express ourselves honestly, we must first be willing and able to unravel what exactly we are, and that requires coming to grips with the myriad influences that have manipulated us since the second we were born.

Unraveling the Past

For Fishman, the unraveling of the mystery of how to honestly express herself in her art hit its stride in 1965, the year she earned her MFA from the University of Illinois, Champaign, and moved to New York City. She brought with her an inheritance of a wide range of powerful influences: her Jewish upbringing; her family heritage having been raised by a mother and an aunt who were both artists; the influence of the gender biases directed toward her as a female artist in a male-dominated field; and the mainstream stigma attached to her sexual identification as a lesbian. On top of all that, she had spent her life studying art and art history, and felt the influence of all of the artists that had come before her.

It was there, in the realm of art history, that her personal revolution really began to bloom. She had the realization that every artist she had ever studied in school was a male. Everything she had been taught was geared toward the notion that she did not belong in the art world because of her gender. It was the same inherent bias that had been wielded against female artists throughout history, which kept their work from being shared and kept their names from being known. Fishman took that realization as a rallying point. She halted her way of working and started over, this time approaching art not from the perspective of outside influences, but from the perspective of actually trying to discover the truth of who she uniquely and honestly is.

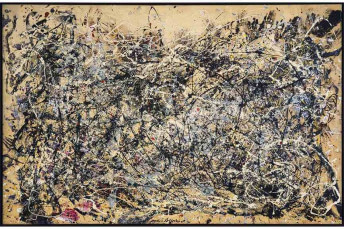

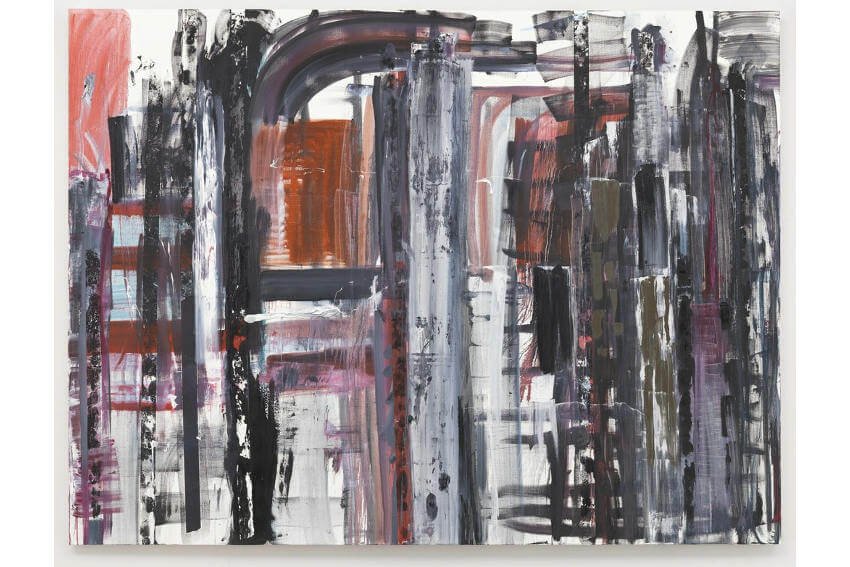

Louise Fishman - San Stae 2017, Oil on linen, 72 × 96 in, 182.9 × 243.8 cm, photo credits Cheim & Read, New York

Louise Fishman - San Stae 2017, Oil on linen, 72 × 96 in, 182.9 × 243.8 cm, photo credits Cheim & Read, New York

Tearing Apart the Past

When she first moved to New York City, Fishman was an abstract painter working in the prevailing modes of her time, modes that leaned toward geometric abstraction and Minimalism. But the revelation that everything she had ever learned about painting had emerged out of a vast patriarchal conspiracy to convolute reality convinced her that following the prevailing trends was a road to mediocrity and homogeny. The brushes, the canvases, the supports, the techniques, the styles: all of it was inherited from a false past.

She cut up some of the paintings she had been working on and then, though she never had any use for such things before, taught herself the crafts associated with historical femininity, such as sewing and quilting, and used those skills to sew the scraps of her cut up paintings into new works. The new pieces evoked primitive clothing or blankets. They were raw and personal. They spoke to a return to the primal beginnings of art: the first artists were women, after all. And they also conveyed a powerful allegory: a fresh aesthetic position literally reclaimed, reconstructed from the shattered, inauthentic myth of the past.

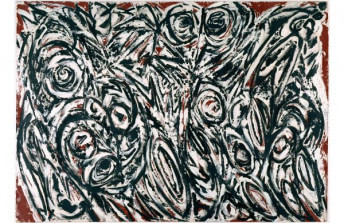

Louise Fishman - Sharps and Flats, 2017, Oil on linen, 70 × 90 in, 177.8 × 228.6 cm, photo credits Cheim & Read, New York

Louise Fishman - Sharps and Flats, 2017, Oil on linen, 70 × 90 in, 177.8 × 228.6 cm, photo credits Cheim & Read, New York

Finding a Way Forward

During this same time, Fishman was also actively engaged in the social, cultural and political scenes of New York. She was an activist who participated in various direct action coalitions that were fighting for feminist ideals. She was also an outspoken advocate within the lesbian community. These activities were essential to the defense of herself and her community. But they were also representative of the larger heritage into which she was born. How much does our gender, our sexuality, our politics, our religion and our family history really determine who we truly are? By allowing such elements to control our lives and influence our art making, are we just playing into the hand of the same cultural myths we are supposedly resisting?

While searching for her way through such questions, Fishman kept working to find her unique aesthetic position as an artist. She embraced an experimental approach to her work. She lived in a part of lower Manhattan where an infinite array of found objects, strange materials, and unusual consumer products were available. Rather than relying on the traditional, predictable, inherited ways of making art, she embraced whatever was actually around her, building work from the material reality of her authentic existence. She worked large, small, two dimensional, three-dimensional: whatever grew out of her environment and the moment. She developed a diverse approach to art making that owed less to the history of art than to its spirit.

Louise Fishman - Untitled, 2011, Acrylic on rusted metal, 1 1/4 × 8 1/2 × 7 1/4 in, 3.2 × 21.6 × 18.4 cm, ICA Philadelphia, Philadelphia, photo credits Cheim & Read, New York

Louise Fishman - Untitled, 2011, Acrylic on rusted metal, 1 1/4 × 8 1/2 × 7 1/4 in, 3.2 × 21.6 × 18.4 cm, ICA Philadelphia, Philadelphia, photo credits Cheim & Read, New York

Returning to Painting

Eventually, her aesthetic experiments brought Fishman back to painting. But her new engagement with painting was more honest and more personal than before. She employed surfaces that communicated her individual character and used mediums to which she was personally drawn, which helped to communicate the layers of feeling inherent in the work. She employed tools and techniques outside the usual realm of the painting studio. And the topics she addressed in her work had also evolved. She made a body of work known as Angry paintings, which use direct, simple text declarations to challenge cultural responses to female emotion. And after a visit to concentration camps in Germany, she developed a body of work that confronted her personal feelings about her family history, her Jewish past, and the many other ways she viscerally related to the persecution embodied in such places.

Today her work conveys a mature, timeless sincerity. Throughout her decades-long journey toward honest self-expression, Fishman has reinvented painting as a personal mode of self expression. She took it back to its roots and brought it forward again in time, now with her as its guide rather than the other way around. Along the way she has created, and continues to make, a remarkably diverse oeuvre, which includes works on paper, tiny paintings, text-based works, abstract gestural paintings, sculptural objects, and many other aesthetic phenomena. All of the work possesses a unified aesthetic language of paint and grit. Humanity is evident in its harmonious fluctuation between flaw and precision. A subtle, but heartfelt range of emotion is conveyed through her shifting color palette.

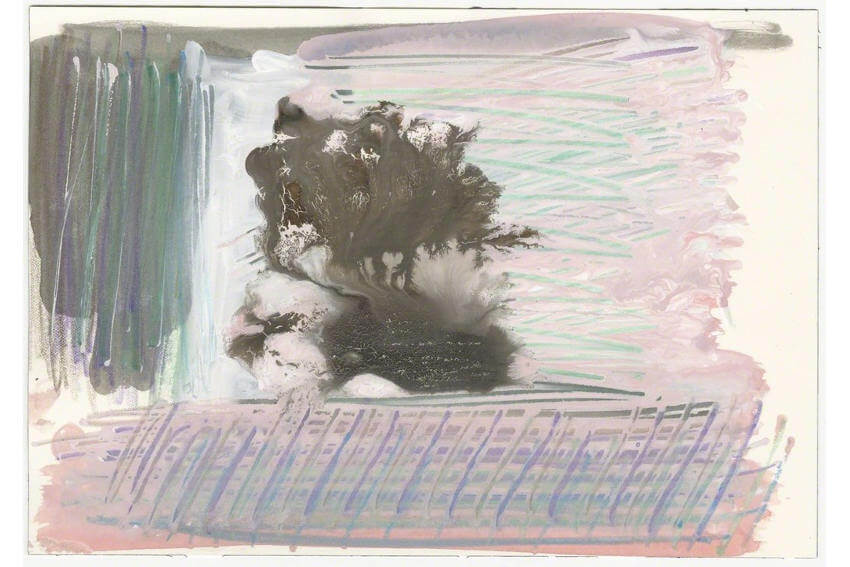

Louise Fishman - Untitled, 2011-2013, Watercolours, 7 1/8 × 10 1/4 in, 18.1 × 26 cm, © Louise Fishman, courtesy of Gallery Nosco | Frameless and Cheim & Read

Louise Fishman - Untitled, 2011-2013, Watercolours, 7 1/8 × 10 1/4 in, 18.1 × 26 cm, © Louise Fishman, courtesy of Gallery Nosco | Frameless and Cheim & Read

A Living Legacy

Personally, aside from her artistic contribution, the more I read about Louise Fishman the more I want to find out more. Her name has joined a short, rotating list that drifts constantly through my head: people I would like to invite to a sort of ultimate cocktail party, at which the rest of us could float through the room unnoticed, listening in the voices of the enlightened, contemplating their wisdom and wit. Fishman is a renowned abstract artist who has been influential in the contemporary art world for more than 40 years. But that is only the beginning of why she is important to me. In fact, I first encountered her name not in an art gallery, but while following an Internet research rabbit hole about counterculture direct action groups from the 1960s and 70s. Fishman has at various times associated with several coalitions working for social reform. The one I was reading about when I first read her name was W.I.T.C.H., or the Women’s International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell.

W.I.T.C.H. engaged in public actions that were aimed at subverting the patriarchal structure on which society is constructed. That alone is something I would love to hear more about. But what most moved me when I was reading about her was a quote she gave in an interview with Alexxa Gotthardt in 2015 for Artsy. While talking about her experience in groups like W.I.T.Ch., Fishman said, “In those groups, everyone had to speak, we were all equalized, and whatever we said couldn’t be questioned. It was testimony: here’s my experience as a woman, and as a woman artist.” That idea of testimony, of the chance to express oneself honestly, unquestioned—that is what I perceive when I look at the work Fishman makes. It is direct and earnest, and complex. It draws my eye in and pulls it cautiously across the surface. Her compositions present themselves like visual timelines, abstract phenomenological diaries. The message they carry with them is that they are not here to be questioned. They demand to be recognized not for what we interpret them to be, not for what we wish them to be, but for what they actually are.

Featured image: Louise Fishman - Untitled, 2011-2013, Watercolours, 12 × 17 7/8 in, 30.5 × 45.4 cm, © Louise Fishman, courtesy of Gallery Nosco | Frameless and Cheim & Read

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio