How Action Painters Changed the Idea of Painting

What is a painting? Some would say a defined, two-dimensional surface on which a painter applies medium in order to create recognizable imagery. But many painters find that definition limiting, and at various times they’ve challenged every aspect of it in order to be free. Action painters are among many groups who have sought liberation from definitions such as the one listed above. Their contribution to artistic freedom was not only to redefine paintings but to alter the very perception of what paintings could be, transforming them from surfaces on which things are painted into arenas in which something occurs.

Content, Medium, Surface and Self

In the early 20th Century, Kandinsky’s pure abstractions proved that a painting’s content doesn’t have to be recognizable. Almost simultaneously, Picasso’s collages shattered perceptions of what could be considered medium. Two decades later, Ben Nicholson’s “relief paintings” challenged the requirement of a painting’s two-dimensional surface. And decades later still Sol LeWitt’s “wall drawings” proved painters don’t have to do their own work. Then right when the definition of a painting was at its most precarious, Yves Klein argued that a painting doesn’t have to be visible at all.

So we ask again: What is a painting? Is it an object? Is it an idea? Is it planned? Is it something that means something? Is it something that exists? Despite their rejection of expectations, Action Painters had an answer to this question, one that was far different than any answer conceived of before. In 1952, the art critic Harold Rosenberg put the answer most perfectly into words, noting that for Action Painters the canvas was “an arena in which to act…What was to go on the canvas was not a picture but an event.”

Jaanika Perna - Spill (REF 858), 2011, 35.8 x 35.8 in, © Jaanika Perna

Jaanika Perna - Spill (REF 858), 2011, 35.8 x 35.8 in, © Jaanika Perna

The Action Painters

The technique utilized by action painters was to work instinctively and quickly, using intuitive gestures to make bold marks on the canvas. Often their gestures resulted in drips, sprays and seemingly extraneous applications of medium to the surface. Though some called those extra marks accidents, the Action painters rejected the idea of accidents, asserting that their actions and their choices resulted in every mark made.

Rosenberg believed that for Action Painters, their canvases were recordings of moments that occurred in their lives. He believed the creative acts of these painters were existential struggles and that the painted canvases were not the story. The existential struggle was the story. The action was the story. The painting was a beautiful relic. Rosenberg successfully argued that their intensely physical gestures and primal connection to subconscious vicissitudes simultaneously expressed individuality and universal humanity.

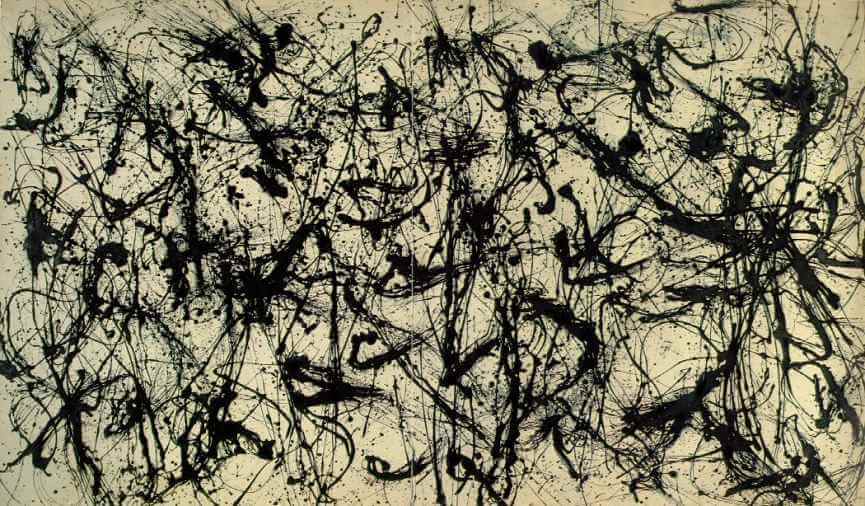

Jackson Pollock - Number 32, 1950, Oil on canvas, 457.5 x 269 cm, Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, Germany, © Jackson Polllock

Different Strokes

The biggest names in first generation Action Painting each developed a unique aesthetic voice, resulting from a highly individualized way of connecting with the canvas. The most famous was Jackson Pollock’s drip technique, in which he would not make direct contact with the canvas, but would rather hover his painting tool just above the surface, directing the paint through momentum and gravity rather than contact.

Driven by the same instinctive approach, the painter Franz Kline developed a much different Action Painting technique, utilizing large house-painting brushes and cheap house paint to make wide, confident marks across the surfaces of his works. Kline’s technique resulted in bold, confident, gestural statements unlike anything his contemporaries were making. His works are iconic of the method, and expressive of a fantastic range of energy and emotion.

Franz Kline - The Ballantine, 1958-1960, Oil on canvas, 72 × 72 in. (182.88 × 182.88 cm), © Franz Kline Estate/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Currents/Events

The legacy of Action Painting continues to influence contemporary artists, who continue using the methodologies of instinct and physicality in order to express their individuality as it relates to the common humanity of our times. One particularly successful example of which would be Jaanika Peerna. Peerna’s medium is graphite and her surface is Mylar. The work she makes is instinctive, fast, and incorporates her entire body in a fluid gesture.

Peerna likens the movements she makes in the creation of her paintings to the motion of water, in particular evoking a storm surge. To execute her works, she holds a bunch of pencils in each hand and then connects the tips of the pencils to the surface of the Mylar. Then in a fluid, sweeping motion of her entire body, she executes a gesture across the surface. The movement results in a confident, intuitive mark across the surface that is a recording of a single natural event in time.

Jaanika Peerna - Falls of Solitude, 2015, Graphite and color pencil on Mylar, 35.8 x 53.9 in., © Jaanika Peerna

Action Required

Expectations imprison artists. Perhaps that’s why among artists, action painters seem to be the most liberated. They benefit from Abstraction’s destruction of all expectations of what painters should paint, and as such are safe from the prison of content. And they further freed themselves from the limitations of what a painting is, by expanding the concept of a painting from a surface on which something is painted to a realm in which something occurs and is recorded in marks.

Featured Image:Jackson Pollock - Number 1, 1948, Oil and enamel paint on canvas, 68 x 8.8 in (172.7 x 264.2 cm), © 2017 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

All images used for illustrative purposes only