The Allure of Lynda Benglis’ Biomorphic Forms

May 3, 2017

In the early 1980s, Lynda Benglis submitted a design for a fountain to an art competition for the Louisiana World Exposition, scheduled for the summer of 1984. A Louisiana native herself, Benglis was delighted when her design was selected. She went to work building it in the Modern Art Foundry in Queens, New York. The process was treacherous and time-consuming. First, Benglis built a massive, lurching, biomorphic form out of chicken wire, a weather balloon, and plastic sheathing. Then, dressed in a hazmat suit, she slowly poured toxic, liquid, polyurethane foam over the massive skeletal object. As one layer dried, Benglis added another. Laborious, open-ended, and sometimes dangerous, her method mimicked the same processes Benglis had witnessed as a child growing up in the lush, waterlogged city of Lake Charles, as nature heaved and lurched to negotiate the lay of the land with the rising and falling motion of the rivers and the sea. Once an image emerged that suited her, Benglis and her team created a mold from the polyurethane shell, from which a bronze sculpture was then created. Fountain mechanisms were then added, and the piece, titled Wave of the World, was shipped to New Orleans for the World Expo. For reasons still not fully understood, the Expo was a financial disaster: the only World’s Fair in history to declare bankruptcy while still open. Afterward, the site was cleared of almost everything: including Wave of the World. Benglis assumed her work had washed out to sea in a hurricane. But three decades later it reappeared: sitting outside, behind a storage facility along with various other random detritus from the Expo. Today, Wave of the World has been restored and now graces Big Lake in New Orleans City Park. Its strange odyssey is a microcosm of the process-based mixture of natural forces and human intervention that Benglis has long employed in her work. As she once described this ethos she has worked hard to maintain: “I am a permissive artist. I allow things to happen.”

What Painting Might Be

Lynda Benglis was born in 1941. She spent her youth exploring the rivers and swamps of her hometown, marveling at the myriad processes that slowly and tirelessly created the mystical-looking, moss-covered, muddy, life-filled terrain. After high school, she followed that pioneering instinct first to Newcomb College in New Orleans, where she earned a BFA in 1964, and then to the Brooklyn Museum Art School in New York, where she enrolled in painting classes. Her earliest artworks imitated nature and its ways, laying the groundwork for an art career that is still guided today by an essential curiosity about materials and the natural world.

Though she is almost universally described as a sculptor, Lynda Benglis describes herself as primarily a painter. Her three-dimensional forms do exist in sculptural space, but they are formed using liquid medium, and the physical motions of drawing. They are paintings without canvases, without predefined surfaces, without restraints: paintings in which medium, gesture, color, line, shape, hue, form and composition have been set free. They are the result of her dream to discover what else painting might be.

Lynda Benglis - Peitho, 2017, Cast polyurethane with pink pigment, © Lynda Benglis - Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York

Lynda Benglis - Peitho, 2017, Cast polyurethane with pink pigment, © Lynda Benglis - Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York

Materials in Action

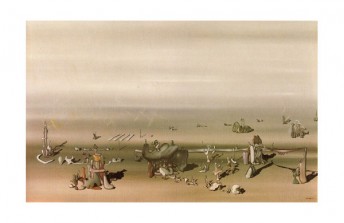

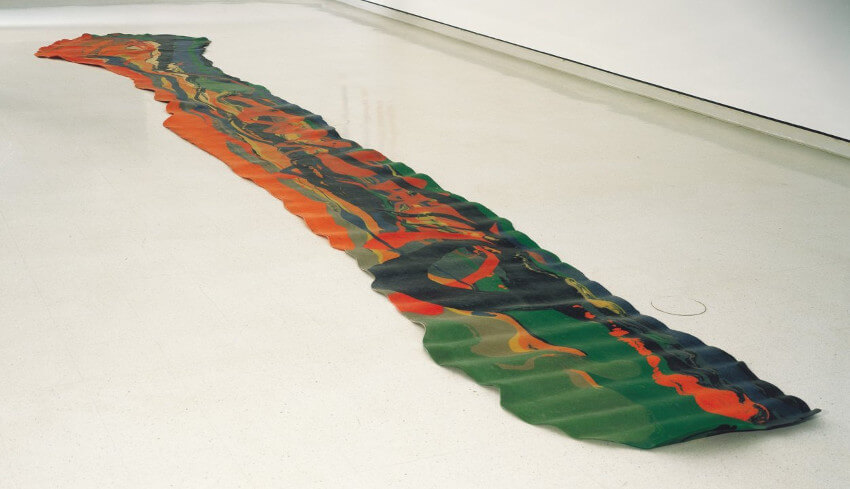

One of the earliest works for which Lynda Benglis received acclaim was a 30-foot long, multi-hued drip of pigmented latex exhibited length-wise on the floor. Titled Fallen Painting, the work had an impact on multiple levels. It spoke in conversation with multiple prevailing aesthetic positions, such as performance art, action painting and conceptual art. It also defined her signature approach of mimicking natural processes, as she had directed liquid materials toward the creation of the form in space while allowing their natural tendencies to express themselves in unexpected ways.

And in addition to its aesthetic impact, Fallen Painting also had a cultural effect. The title was a reference to the idea of a fallen lady. Pouring, dripping and flinging paint was a tendency associated by critics at the time with Abstract Expressionism, a movement those same critics widely, and incorrectly, described as male-driven. With this piece, Benglis re-asserted the female presence in the movement while also moving it forward into something new that she could help define. This statement was only the first of many witty, assertive cultural critiques Benglis has offered so far in her life, earning her a reputation as a pioneering voice arguing for gender equality in the art world.

Lynda Benglis - Fallen Painting 1968, pigmented latex rubber, © Lynda Benglis - Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York

Lynda Benglis - Fallen Painting 1968, pigmented latex rubber, © Lynda Benglis - Licensed by VAGA, New York, New York

Forces in Motion

In addition to pouring, dripping and flinging, Lynda Benglis has explored a huge range of other forces in her work. She has experimented with twisting and squeezing materials, and with gravity and momentum. What all her works have in common is a sense that these forces have been frozen in time, their effects suspended in an aesthetic state suitable for human contemplation. A prime example is her 1971 installation Phantom Five, which features five polyurethane, wall-mounted waveforms. The forms seem to be in a process of becoming. They could be pouring out of the wall, or they could be exploding upward in space. They could be liquid or solid. They are unknown forms, yet they are viscerally, instantly recognizable.

To many people the works Benglis creates are inherently abstract, since their final forms are never known until they manifest. But in another sense there could be nothing more objective than forms that come about through natural processes. Whatever interpretation we give her works, Benglis is eager for us to express it. She believes artworks are never complete until viewers assign them the meaning they await. It is only her intent that her works are not perceived as the results of an ego manifesting predetermined monuments to its vision. Rather, they are the result of processes—some human, some natural—and of curiosity: something inherent to all of us in our most natural, childlike state.

Lynda Benglis - Phantom Five, 1972, installation view at New Museum, New York, 2011

Lynda Benglis - Phantom Five, 1972, installation view at New Museum, New York, 2011

Featured image: Lynda Benglis - The Wave of the World, 1983-84, bronze fountain as installed in New Orleans City Park, photo credit Crista Rock

All images used for illustrative purposes only

By Phillip Barcio